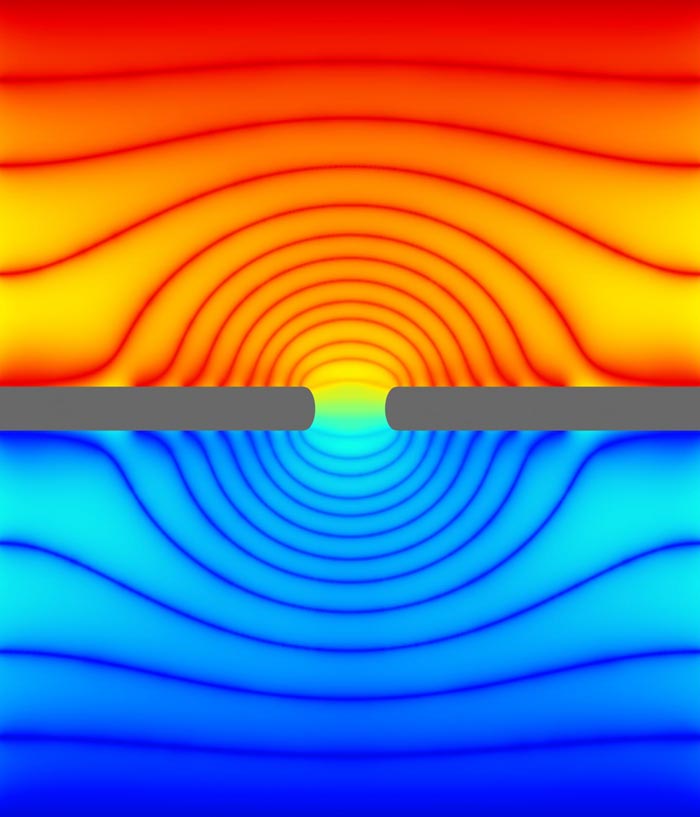

In this simulation, a biological membrane (gray) with an ion channel (center) is immersed in a solution of water and ions. This cross section of a simulation "box" shows the electric potential, the externally supplied "force" that drives ions through the channel. A dazzling pattern emerges in this potential due to the presence of the channel -- the colors show the lines of equal potential. The slowly decaying nature of this pattern in space makes simulations difficult. The golden aspect ratio -- the chosen ratio of height to width of this box -- allows for small simulations to effectively capture the effect of the large spatial dimensions of the experiment.

Credit: NIST

To rapidly transport the right ions through the cell membrane, the tiny channels rely on a complex interplay between the ions and surrounding molecules, particularly water, that have an affinity for the charged atoms. But these molecular processes have traditionally been difficult to model–and therefore to understand–using computers or artificial structures.

Now, researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and their colleagues have demonstrated that nanometer-scale pores etched into layers of graphene–atomically thin sheets of carbon renowned for their strength and conductivity–can provide a simple model for the complex operation of ion channels.

This model allows scientists to measure a host of properties related to ion transport. In addition, graphene nanopores may ultimately provide scientists with efficient mechanical filters suitable for such processes as removing salt from ocean water and identifying defective DNA in genetic material.

NIST scientist Michael Zwolak, along with Subin Sahu (who is jointly affiliated with NIST, the University of Maryland NanoCenter and Oregon State University), has also discovered a way to simulate aspects of ion channel behavior while accounting for such computationally intensive details as molecular-scale variations in the size or shape of the channel.

To squeeze through a cell's ion channel, which is an assemblage of proteins with a pore only a few atoms wide, ions must lose some or all of the water molecules bound to them. However, the amount of energy required to do so is often prohibitive, so ions need some extra help. They get that assistance from the ion channel itself, which is lined with molecules that have opposite charges to certain ions, and thus helps to attract them. Moreover, the arrangement of these charged molecules provides a better fit for some ions versus others, creating a highly selective filter. For instance, certain ion channels are lined with negatively charged molecules that are distributed in such a way that they can easily accommodate potassium ions but not sodium ions.

It's the selectivity of ion channels that scientists want to understand better, both to learn how biological systems function and because the operation of these channels may suggest a promising way to engineer non-biological filters for a host of industrial uses.

By turning to a simpler system–graphene nanopores–Zwolak, Sahu, and Massimiliano Di Ventra of the University of California, San Diego, simulated conditions that resemble the activity of actual ion channels. For example, the team's simulations demonstrated for the first time that nanopores could be made to permit only some ions to travel through them by changing the diameter of the nanopores etched in a single sheet of graphene or by adding additional sheets. Unlike biological ion channels, however, this selectivity comes from the removal of water molecules only, a process known as dehydration.

Graphene nanopores will allow this dehydration-only selectivity to be measured under a variety of conditions, another new feat. The researchers reported their findings in recent issues of Nano Letters and Nanoscale.

In two preprints (https:/

###

Papers: S. Sahu, M. Di Ventra, and M. Zwolak. Dehydration as a Universal Mechanism for Ion Selectivity in Graphene and Other Atomically Thin Pores. Nano Letters. Published online 5 July 2017. DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b01399

S. Sahu and M. Zwolak. Ionic selectivity and filtration from fragmented dehydration in multilayer graphene nanopores. Nanoscale. Published online 25 July 2017. DOI: 10.1039/C7NR03838K