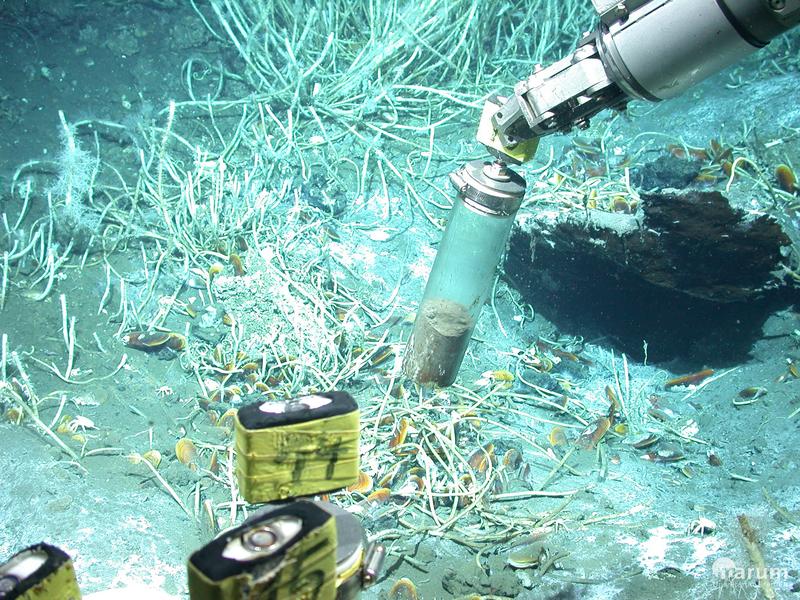

The submersible vehicle MARUM-QUEST samples for sediment at oil seeps in the Gulf of Mexico.

MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences

The tiny organisms cling to oil droplets and perform a great feat: As a single organism, they may produce methane from oil by a process called alkane disproportionation. Previously this was only known from symbioses between bacteria and archaea.

Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology have now found cells of this microbe called Methanoliparia in oil reservoirs worldwide.

Crude oil and gas naturally escape from the seabed in many places known as “seeps”. There, these hydrocarbons move up from source rocks through fractures and sediments towards the surface, where they leak out of the ground and sustain a diversity of densely populated habitats in the dark ocean.

A large part of the hydrocarbons, primarily alkanes, is already degraded before it reaches the sediment surface. Even deep down in the sediment, where no oxygen exists, it provides an important energy source for subsurface microorganisms, amongst them some of the so-called archaea.

These archaea were good for many surprises in recent years. Now a study led by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, Germany, and the MARUM, Centre for Marine Environmental Sciences, provides environmental information, genomes and first images of a microbe that has the potential to transform long-chain hydrocarbons to methane. Their results are published in the journal mBio.

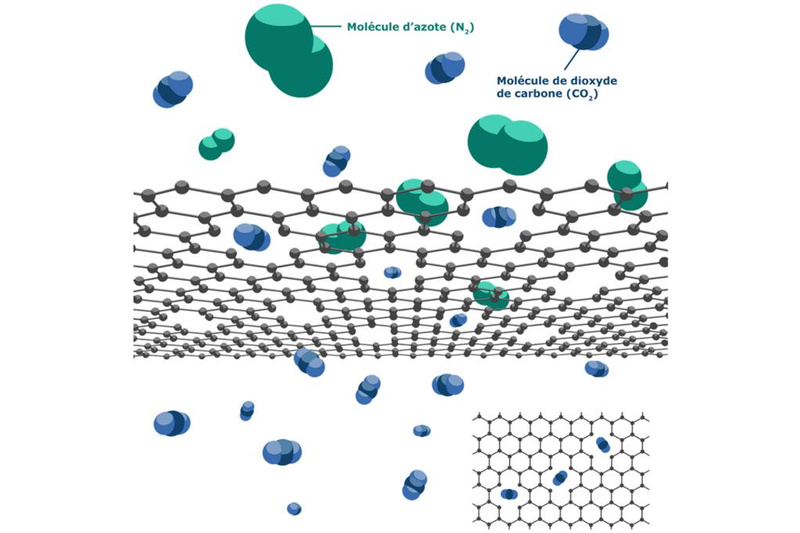

Splitting oil into methane and carbon dioxide

This microbe, an archaeon named Methanoliparia, transforms the hydrocarbons by a process called alkane disproportionation: It splits the oil into methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2). Previously, this transformation was thought to require a complex partnership between two kinds of organisms, archaea and bacteria.

Here the team from Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology and MARUM presents evidence for a different solution. “This is the first time we get to see a microbe that has the potential to degrade oil to methane all by itself”, first-author Rafael Laso-Pérez explains.

During a cruise in the Gulf of Mexico, the scientists collected sediment samples from the Chapopote Knoll, an oil and gas seep, 3000 m deep in the ocean. Back in the lab in Bremen, they carried out genomic analyses that revealed that Methanoliparia is equipped with novel enzymes to use the quite unreactive oil without having oxygen at hand.

“The new organism, Methanoliparia, is kind of a composite being”, says Gunter Wegener, the initiator and senior author of this study. “Some of its relatives are multi-carbon hydrocarbon-degrading archaea, others are the long-known own methanogens that form methane as metabolic product.” With the combined enzymatic tools of both relatives, Methanoliparia activates and degrades the oil but forms methane as final product.

Moreover, the visualization of the organisms supports the proposed mechanism: “Microscopy shows that Methanoliparia cells attach to oil droplets. We did not find any hints that it requires bacteria or other archaea as partners”, Wegener continues.

Very frequent and globally distributed

Methanogenic microorganisms have been important for the earth’s climate through time as their metabolic product, methane, is an important greenhouse gas that is 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Thus, Laso-Pérez and his colleagues where also interested to find out about how widespread this novel organism is.

“We scanned DNA-libraries and found that Methanoliparia is frequently detected in oil reservoirs – and only in oil reservoirs – all over the oceans. Thus, this organism could be a key agent in the transformation of long-chain hydrocarbons to methane”, says Laso-Pérez.

Thus, the scientists next want to dig deeper into the secret life of this microbe. “Now we have the genomic evidence and pictures about the wide distribution and surprising potential of Methanoliparia. But we can’t yet grow them in the lab. That will be the next step to take. It will enable us to investigate many more exciting details”, Wegener explains.

“For example, whether it is possible to reverse the process, which would ultimately allow us to transform a greenhouse gas into fuel. “

Dr. Rafael Laso-Pérez

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany

Phone: +49 421 2028-876

E-Mail: rlperez@mpi-bremen.de

Dr. Gunter Wegener

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen, Germany

Phone: +49 421 2028-867

E-Mail: gwegener@mpi-bremen.de

Dr. Fanni Aspetsberger

Press Officer

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology,

Bremen, Germany

Phone: +49 421 2028-947

E-Mail: faspetsb@mpi-bremen.de

Rafael Laso-Pérez, Cedric Hahn, Daan M. van Vliet, Halina E. Tegetmeyer, Florence Schubotz, Nadine T. Smit, Thomas Pape, Heiko Sahling, Gerhard Bohrmann, Antje Boetius, Katrin Knittel, Gunter Wegener: Anaerobic degradation of non-methane alkanes by Ca. Methanoliparia in hydrocarbon seeps of the Gulf of Mexico. mBio. DOI: 10.1128/mBio.01814-19

https://www.mpi-bremen.de/en/Page3832.html