Lab of Charles Zuker

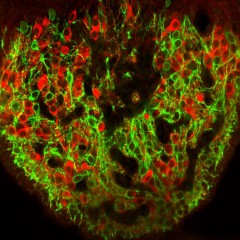

CUMC researchers have identified two types of neurons that control thirst. This image of a mouse brain shows the two neurons, CAMKII (in red) that triggers thirst and VGAT (in green) that inhibit thirst.

Neurons that trigger our sense of thirst—and neurons that turn it off—have been identified by Columbia University Medical Center neuroscientists. The paper was published today in the online edition of Nature.

For years, researchers have suspected that thirst is regulated by neurons in the subfornical organ (SFO), in the hypothalamus. But it has been difficult to pinpoint exactly which neurons are involved. “When researchers used electrical current to stimulate different parts of the SFO of mice, they got confusing results,” said lead author Yuki Oka, PhD, a postdoctoral research scientist in the laboratory of Charles S. Zuker, PhD, professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics and of neuroscience, a member of the Kavli Institute for Brain Science and the Mortimer B. Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator at CUMC.

The CUMC team hypothesized that there are at least two types of neurons in the SFO, including ones that drive thirst and others that suppress it. “Those electrostimulation experiments were probably activating both types of neurons at once, so they were bound to get conflicting results,” said Yuki Oka.

To test their hypothesis, Drs. Oka and Zuker turned to optogenetics, a more precise technique for controlling brain activity. With optogenetics, researchers can control specific sets of neurons in the brain after inserting light-activated molecules into them. Shining light onto these molecules turns on the neurons without affecting other types of neurons nearby.

These “mind-control” experiments revealed two types of neurons in the SFO that control thirst: CAMKII neurons, which turn thirst on, and VGAT neurons, which turn it off.

When the researchers turned on CAMK11 neurons, mice immediately began to seek water and to drink intensively. This behavior was as strong in well-hydrated mice as in dehydrated ones. Once the neurons were shut off—by turning off the light—the mice immediately stopped drinking.

The researchers also found that light-stimulation of the CAMKII neurons did not induce feeding behavior. In addition, light-induced thirst was specific for water and did not increase the animals’ consumption of other fluids, including glycerol and honey.

Similar experiments with VGAT neurons showed that these neurons act to turn off thirst. When the researchers turned on these neurons with light, dehydrated mice immediately stopped drinking, even if they were drinking water. “Together, these findings show that the SFO is a dedicated brain system for thirst,” said Dr. Oka.

“The SFO is one of few neurological structures that is not blocked by the blood-brain barrier—it’s completely exposed to the general circulation,” said Dr. Oka. “This raises the possibility that it may be possible to develop drugs for conditions related to thirst.

The article is titled, “Thirst Driving and Suppressing Signals Encoded by Distinct Neural Populations in the Brain.” The other contributor is Mingye Ye, also a postdoctoral fellow in Zuker’s lab at CUMC.

The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

The study was funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and grants from the NIH (1R01NS076774, 1R01DA035025) to Professor Zuker. Dr. Oka recently moved to the California Institute of Technology as a newly appointed assistant professor.

Columbia University Medical Center provides international leadership in basic, preclinical, and clinical research; medical and health sciences education; and patient care. The medical center trains future leaders and includes the dedicated work of many physicians, scientists, public health professionals, dentists, and nurses at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, the Mailman School of Public Health, the College of Dental Medicine, the School of Nursing, the biomedical departments of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and allied research centers and institutions. Columbia University Medical Center is home to the largest medical research enterprise in New York City and State and one of the largest faculty medical practices in the Northeast. For more information, visit cumc.columbia.edu or columbiadoctors.org

Contact Information

Karin Eskenazi, 212-342-0508, ket2116@columbia.edu