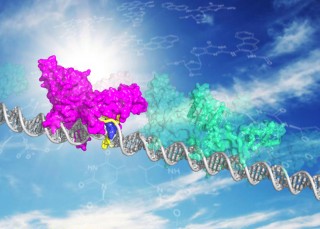

Illustration: Myrna Romero and Jung-Hyun Min.

XPC DNA repair protein shown in two modes, patrolling undamaged DNA (in green) and bound to DNA damage site (magenta, with blue XPC insert opening the site). The sun behind the molecule is a reminder that the sun is the primary source of lesions recognized by XPC.

Usually, the repair protein zips along quickly, says Anjum Ansari, UIC professor of physics and co-principal investigator on the study, published this month in Nature Communications.

“If the DNA is normal and the protein is searching, the interaction that the protein makes with the DNA is not very tight, and the protein is able to wander at some speed,” Ansari said.

“When the protein encounters a damaged DNA, it’s not quite like a normal DNA , it may be a little twisted or more flexible. The protein ‘stumbles’ at that spot and gets a little stalled, enough to give it a little bit more time at the damaged site,” she said. “The longer it sits, the higher the probability that it will open the DNA and initiate repair.”

This ‘stumble’ gives the protein time to flip out the damaged nucleotide building blocks of the DNA and recruit other proteins that begin repair, said Jung-Hyun Min, assistant professor of chemistry at UIC and co-principal investigator on the study.

The protein, xeroderma pigmentosum C or XPC, is important for the repair of DNA damaged by environmental insults, like the chemicals in cigarette smoke and pollutants, which makes it important for preventing cancers, Min said. Dysfunctional XPC may lead to a 1,000-fold increase in the risk of skin cancer.

How the protein can find a lesion hidden among perhaps 100,000 times as many undamaged nucleotides has been a mystery, Min said. XPC is unusual in that it does not have a “pocket” that fits one specific damaged structure while rejecting others that do not fit well. Instead, it recognizes damage indirectly, and so is able to repair a variety of derangements.

In order to see how XPC distinguishes between normal and damaged DNA, the researchers used a chemical trick to bind the protein to a single site on intact DNA. To their surprise, they found that the protein flipped open the nucleotides on undamaged DNA just as it does at a bad spot.

The finding suggested that, if held in one place long enough, XPC could open even undamaged DNA. Using a technique called temperature-jump perturbation spectroscopy to observe the interaction of XPC with DNA in real time, the researchers determined that the protein needed several milliseconds to flip open DNA at a damaged site.

“We think it could take as much 4,000 times as long to open DNA at an undamaged versus damaged site,” said Ansari. The XPC protein moves too quickly to engage undamaged DNA, but is stalled by a twisted damage site long enough to flip out the bad nucleotides and initiate repair.

This dependence on how quickly the protein could open up the DNA before moving on suggests an entirely new kind of binding-site recognition, said Min.

“This has a potential to explain the kind of phenomena that we couldn’t explain before,” Min said, such as how the protein turns up in some places where the DNA does not harbor damage that XPC would be expected to recognize on its own.

“This may be done, for example, through interactions with other proteins that can bring XPC there and stall it for a moment,” she said. “It may be that all you need is to bring the protein to these sites and stall it for a moment.”

The researchers believe that this “delay-triggered kinetic gating” could be a common mechanism among many other types of DNA recognition proteins.

Xuejing Chen, UIC chemistry, and Yogambigai Velmurugu, UIC physics, are co-first authors on the study. Beomseok Park, Yoonjung Shim of UIC chemistry; Guanqun Zheng, and Chuan He of University of Chicago; Younchang Kim of Argonne National Laboratory and Lili Liu and Bennett Van Houten of the University of Pittsburgh are co-authors.

This study was funded by the UIC’s Chancellor’s Discovery Fund; Chicago Biomedical Consortium’s Catalyst Award with support from the Searle Funds at The Chicago Community Trust; National Institutes of Health grants GM0771440 and 1RO1ES019566; National Science Foundation Grants MCB-0721937 and MCB-115821; and a UIC startup fund.

Contact Information

Jeanne Galatzer-Levy

Associate Director, News Bureau

jgala@uic.edu

Phone: 312-996-1583