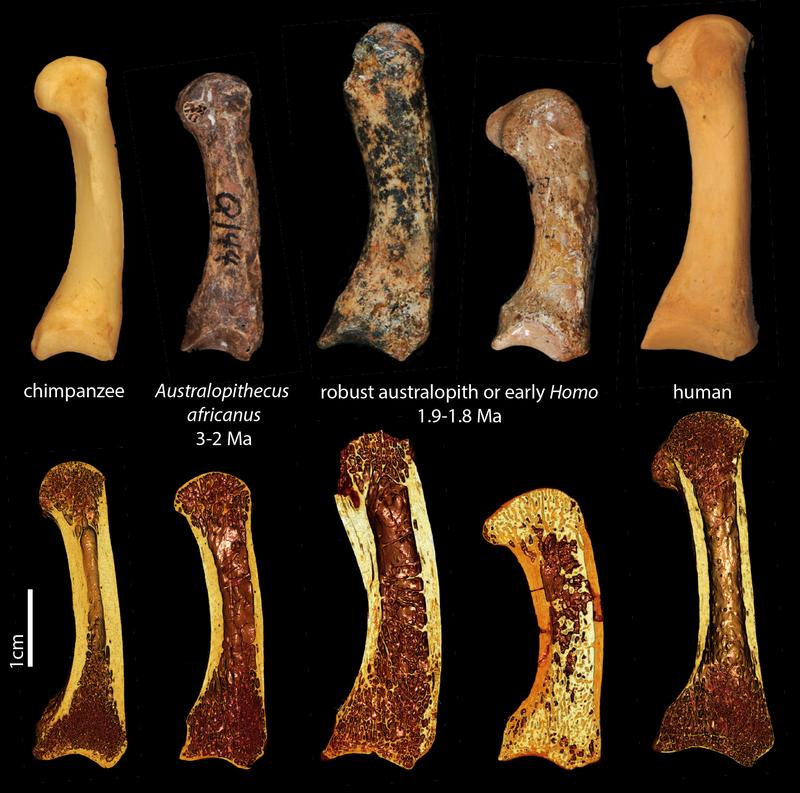

The first metacarpals of a chimp, the fossil australopiths, and a human (top row). The bottom row constists of images from micro-computertomography-scans of the same specimens, showing a cross-section of the trabecular structure inside.

© Tracy Kivell

Some of the morphological characteristics of the human hand are different from that of other primates enabling us to grab objects with precision and use them exerting a force. Yet, how did our early human ancestors use their hands?

This question was long debated among scientists. Anthropologists from the University of Kent, working with researchers from University College London, the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany and the Vienna University of Technology in Austria, have produced the first research findings to support archaeological evidence for stone tool use among fossil australopiths three to two million years ago and found that Australopithecus africanus used their hands the way modern humans do.

The distinctly human ability for forceful precision (e.g., when turning a key) and power “squeeze” gripping (e.g., when using a hammer) is linked to two key evolutionary transitions in hand use: a reduction in arboreal climbing and the manufacture and use of stone tools. However, it is unclear when these locomotory and manipulative transitions occurred.

Matthew Skinner and Tracy Kivell of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the University of Kent used new techniques to reveal how fossil species were using their hands by examining the internal spongey structure of bone called trabeculae. Trabecular bone remodels quickly during life and can reflect the actual behaviour of individuals in their lifetime.

“Over time these structures adapt in a way that enables them to handle the daily loads in the best way possible“, says Dieter Pahr of the Institute of Lightweight Design and Structural Biomechanics at the Vienna University of Technology where special computer algorithms for the analysis of the computer tomography images of the bones had been developed.

The researchers first examined the trabeculae of hand bones of humans and chimpanzees. They found clear differences between humans, who have a unique ability for forceful precision gripping between thumb and fingers, and chimpanzees, who cannot adopt human-like postures. This unique human pattern is present in known non-arboreal and stone tool-making fossil human species, such as Neandertals.

The research shows that Australopithecus africanus, a three to two million-year-old species from South Africa traditionally considered not to have engaged in habitual tool manufacture, has a human-like trabecular bone pattern in the bones of the thumb and palm (the metacarpals) consistent with forceful opposition of the thumb and fingers typically adopted during tool use.

“This new evidence changes our understanding of the behaviour of our early ancestors and, in particular, suggests that in some aspects they were more similar to humans than we previously thought”, says Matthew Skinner of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the University of Kent.

These results support previously published archaeological evidence for stone tool use in australopiths and provide skeletal evidence that our early ancestors used human-like hand postures much earlier and more frequently than previously considered. “There is growing evidence that the emergence of the genus Homo did not result from the emergence of entirely new behaviors but rather from the accentuation of traits already present in Australopithecus, including tool making and meat consumption”, says Jean-Jacques Hublin, director at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

Contact

Prof. Dr. Jean-Jacques Hublin

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig

Phone: +49 341 3550-351

Fax: +49 341 3550-399

Email: hublin@eva.mpg.de

Dr. Matthew Skinner

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig

University of Kent, Großbritannien

Phone: +44 1227 823937

Email: M.Skinner@kent.ac.uk

Sandra Jacob

Press and Public Relations

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig

Phone: +49 341 3550-122

Fax: +49 341 3550-119

Email: info@eva.mpg.de

Original publication

Matthew M. Skinner, Nicholas B. Stephens, Zewdi J. Tsegai, Alexandra C. Foote, N. Huynh Nguyen,Thomas Gross, Dieter H. Pahr, Jean-Jacques Hublin,Tracy L. Kivell

Human-like hand use in Australopithecus africanus

Science, 23 January 2015