Going against the flow – Targeting bacterial motility to combat disease

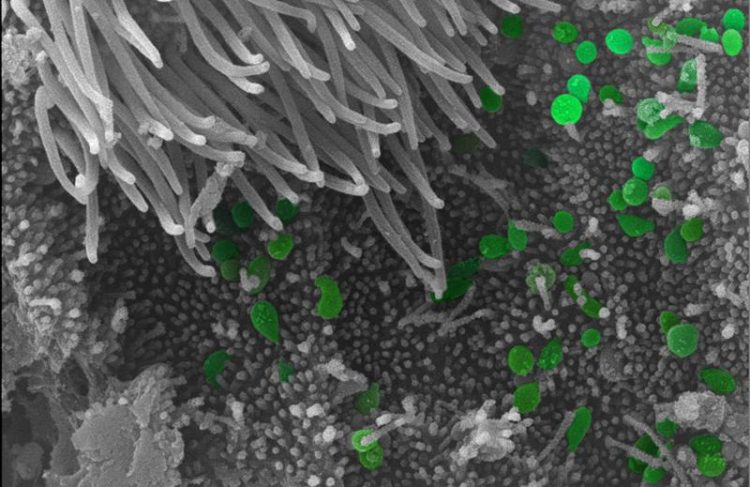

Mycoplasma gallisepticum on epithelial cells of a chicken trachea. Photo: Michael Szostak / Vetmeduni Vienna

Scientists at the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna have now identified the proteins responsible for this gliding mechanism. Interrupting the gliding mechanism could be a way to make the bacteria less virulent, but it could also help in the development of vaccines against the pathogen. The results were published in the journal Veterinary Research.

Mycoplasma gallisepticum causes chronic respiratory disease in birds. The illness particularly affects domestic chicken and turkey flocks. The bacteria are especially life-threatening for the animals when they occur in combination with other infections. In order to control the spread of the disease, poultry farms in the EU must be proven free from Mycoplasma gallisepticum or face being closed.

Mycoplasma gallisepticum is related to the human pathogen Mycoplasma pneumoniae, the causative agent of human bronchitis and pneumonia. Mycoplasmas are among the world’s smallest microorganisms. Scientists even speak of degenerative bacteria. Over the course of evolution, mycoplasmas have thrown most of their genetic material over board, resulting in one of the smallest bacterial genomes. This is what makes them such efficiently adapted pathogens in humans and animals.

At least three proteins responsible for the gliding mechanism

The gliding motility of M. gallisepticum was first observed in the 1960s. However, it has so far been unclear how exactly the gliding mechanism works and which proteins make gliding possible. First author Ivana Indikova and study director Michael Szostak of the Institute of Microbiology at the Vetmeduni Vienna have now found that gliding requires the proteins GapA, CrmA and Mgc2. “If the bacteria are missing one of these three proteins, they are no longer able to move. We want to know if non-motile mycoplasmas are less infectious. If that were the case, we could target the motility genes to turn them off and so render the bacteria harmless,” Szostak explains.

Gliding motility could even contribute to the ability of mycoplasmas to invade and traverse body cells. This could allow them to safely evade the body’s immune system and the infection could spread efficiently through the host body.

The experts can also imagine the development of a vaccine. “Non-motile and non-pathogenic bacteria could form the basis for a new vaccine which the immune system could recognize and fight without causing any illness in the organism,” explains Szostak.

Do gliding mycoplasmas go against the flow?

The ability to move thus gives the pathogens certain advantages. It remains unknown, however, which stimuli M. gallisepticum responds to when gliding. Szostak suspects: “Most mycoplasmas cannot glide. Gliding species have so far been found only in the respiratory and genital tracts – places in which there is a directional mucus flow. We believe that the gliding bacteria possibly move against this flow in order to reach deeper-lying regions of the body. We are currently planning further experiments to attempt to answer this question.”

Service:

The article „First identification of proteins involved in motility of Mycoplasma gallisepticum”, by Ivana Indikova, Martin Vronka and Michael P. Szostak was published in the journal Veterinary Research. DOI: 10.1186/s13567-014-0099-2 http://www.veterinaryresearch.org/content/45/1/99

About the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna

The University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna in Austria is one of the leading academic and research institutions in the field of Veterinary Sciences in Europe. About 1,300 employees and 2,300 students work on the campus in the north of Vienna which also houses five university clinics and various research sites. Outside of Vienna the university operates Teaching and Research Farms. http://www.vetmeduni.ac.at

Scientific Contact:

Dr. Michael Szostak

Institute of Microbiology

University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna (Vetmeduni Vienna)

T +43 1 20577-2104

michael.szostak@vetmeduni.ac.at

Released by:

Susanna Kautschitsch

Science Communication / Public Relations

University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna (Vetmeduni Vienna)

T +43 1 25077-1153

susanna.kautschitsch@vetmeduni.ac.at

Weitere Informationen:

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

NASA: Mystery of life’s handedness deepens

The mystery of why life uses molecules with specific orientations has deepened with a NASA-funded discovery that RNA — a key molecule thought to have potentially held the instructions for…

What are the effects of historic lithium mining on water quality?

Study reveals low levels of common contaminants but high levels of other elements in waters associated with an abandoned lithium mine. Lithium ore and mining waste from a historic lithium…

Quantum-inspired design boosts efficiency of heat-to-electricity conversion

Rice engineers take unconventional route to improving thermophotovoltaic systems. Researchers at Rice University have found a new way to improve a key element of thermophotovoltaic (TPV) systems, which convert heat…