While whales and dolphins spend their entire life in the ocean, these air-breathing mammals actually evolved from terrestrial species. The transition from land to water in the ancestors of modern whales and dolphins about 50 million years ago was accompanied by profound anatomical, physiological, and behavioral adaptations that facilitated life in water.

However, which changes in the DNA underlie these adaptations remains incompletely understood. To reveal them, researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), the MPI for the Physics of Complex Systems (MPI-PKS), and the Center for Systems Biology Dresden (CSBD) systematically searched for genes that were lost in the ancestor of today’s whales and dolphins.

The research team discovered 85 gene losses, some of which likely helped whales to thrive in their new habitat. These findings are published in the journal Science Advances.

Given the appearance of a whale or dolphin, it is easy to mistake them for large fish. However, just like their closest living relatives such as hippopotamuses or cows, whales are air-breathing mammals whose evolutionary ancestors adapted to spending their entire live in water. During this transition from land to water, remarkable changes in the anatomy and physiology occurred.

For example, whales and dolphins have streamlined bodies and lost their body hair to become faster swimmers. They evolved a thick layer of blubber for insulation. Their hind limbs were lost while large tail flukes evolved for propulsion. Increased oxygen stores facilitate long dives and a flexible ribcage allows their lung to collapse while diving to depths of 100 meters and more.

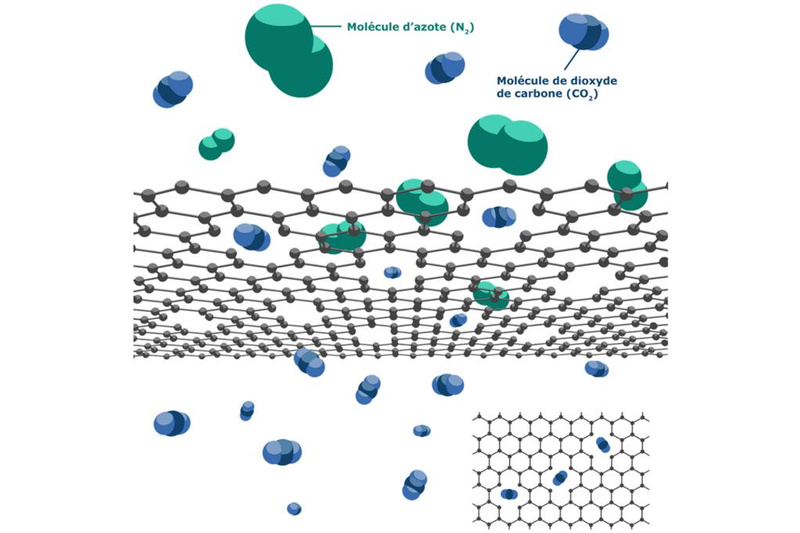

The changes in the DNA (the genome) that made those adaptations possible were poorly understood so far. That’s why a team of researchers around Michael Hiller at the MPI-CBG, the MPI-PKS, and the CSBD together with colleagues from the University of California and the American Museum of Natural History in New York carried out a systematic search for genes that got lost during this evolutionary transition.

To this end, the researchers examined the genomes of today’s whales, dolphins and other mammals for mutations that inactivate genes. Matthias Huelsmann, the lead author of the study, explains: “We searched for mutations that occur in all whales and dolphins, but not in the Hippopotamus or other terrestrial mammals. Such shared mutations tell us that the respective gene got lost in the whale ancestors.”

This systematic search revealed 85 gene losses. Many of these genes were probably lost because their function was no longer useful. For example, saliva is no longer useful in lubricating food in an aquatic environment, which likely explains why a gene involved in saliva secretion was lost. Remarkably, the loss of other genes may have even provided an advantage for ancestral whales.

“One gene loss that we discovered likely improves how whales repair a specific type of DNA damage. This type of DNA damage is caused by severe oxygen shortages that whales regularly face when diving. If the DNA is not repaired properly, this could lead to tumors or have other negative consequences”, reports Matthias Huelsmann. Similarly, losses of other genes likely protect diving whales from the formation of blood clots and lung damage.

But not only anatomy and physiology changed in the aquatic environment, behavioral characteristics of whales and dolphins changed too. In particular, the necessity to constantly surface for breathing led to a peculiar type of sleep. Similar to migrating birds, only half of a whale’s brain sleeps at a time, while the other half coordinates movement and breathing. Interestingly, the researchers found that all genes required to produce melatonin, the hormone that regulates sleep, have been lost in whales and dolphins. These gene losses may have been a precondition for adopting this special type of sleep.

Michael Hiller, who oversaw this study, concludes: “We found new evidence that loss of genes during evolution can sometimes be beneficial, which supports previous results from our lab suggesting that gene loss is an important evolutionary mechanism.”

About the MPI-CBG

The Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) is one of more than 80 institutes of the Max Planck Society, an independent, non-profit organization in Germany. 600 curiosity-driven scientists from over 50 countries ask: How do cells form tissues? The basic research programs of the MPI-CBG span multiple scales of magnitude, from molecular assemblies to organelles, cells, tissues, organs, and organisms.

About the MPI-PKS

The goal of the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems (MPI-PKS) is to contribute to the research in the field of complex systems in a globally visible way and to promote it as a subject. Furthermore, the MPI-PKS invests into passing on the innovation generated in the field of complex systems as quickly and efficiently as possible to the young generation of scientists at universities. This requires a high degree of creativity, flexibility and communication with universities. The concept rests on two pillars: in-house research and a program for visiting scientists. The latter not only covers individual scholarships for guest scientists at the institute, but also 20 international workshops and seminars per year.

About the CSBD

The Center for Systems Biology Dresden (CSBD) is a cooperation between the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), the Max Planck Institute for the Physics of Complex Systems (MPI-PKS), and the TU Dresden. The interdisciplinary center brings physicists, computer scientists, mathematicians, and biologists together. The scientists develop theoretical and computational approaches to biological systems across different scales, from molecules to cells and from cells to tissues.

Dr. Michael Hiller

+49 (0) 351 210 2781

hiller@mpi-cbg.de

Matthias Huelsmann, Nikolai Hecker, Mark S. Springer, John Gatesy, Virag Sharma and Michael Hiller: “Genes lost during the transition from land to water in cetaceans highlight genomic changes associated with aquatic adaptations” Science Advances, 25. September, 2019