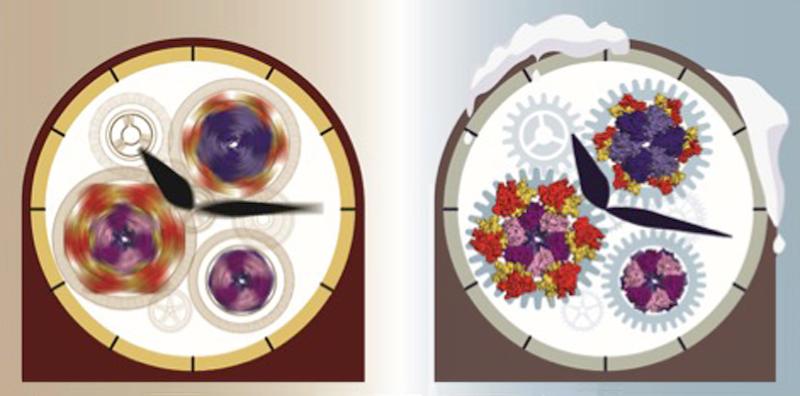

Cooling down the molecular clock of cyanobacteria puts its cogwheels to rest. It allows to visualize details of their appearance and assembly by cryo-electron microscopy.

Illustration: P. Lössl

Ten years ago, researchers discovered that the biological clock in cyanobacteria consists of only three protein components: KaiA, KaiB and KaiC. These are the building blocks – the gears, springs and balances – of an ingenious system resembling a precision Swiss timepiece.

In 2005, Japanese scientists published an article in Science showing that a solution of these three components in a test tube could run a 24-hour cycle for days when a bit of energy was added. However, the scientists were not able to uncover the exact operation of the system, despite its relative simplicity.

William Faulkner

How could the scientists resolve the working of the individual pieces? “In the end, the trick to understand the ticking biological clock in cyanobacteria was to literally make time stop”, tells research leader Albert Heck from Utrecht University. “Or as William Faulkner, Nobel Prize Laureate in Literature said: ‘Only when the clock stops does time come to life.’ Faulkner spoke taking a pause in the constant haste of life. That was also the trick here. We slowed the biological clock by running it in the fridge for a week. In the literal sense we have frozen the time.”

New combination

In addition to stopping time, the researchers applied a new combination of cutting-edge research techniques. With one technique, they were able to determine how often each of the three protein complexes – KaiA, KaiB and KaiC – assembled or disassembled in a single 24-hour cycle. This taught them which collections of protein components – combinations of gears, springs and balances – determine the daily rhythm.

Zooming in

They then stopped the clock at specific moments by reducing the temperature. This allowed them to use a variety of techniques to zoom in in great detail on the structure of the collection of protein components at that moment – the position of the gears, springs and balances. In so doing, they identified the two structures that are vital to understanding how the clock works. The researchers could then derive how the wheels turn by determining the transitions from one structure to another. This produced a model that shows exactly how only three protein components form a precision timepiece that operates on a 24-hour cycle.

“Even though the biological clock of cyanobacteria is very old in terms of geological history, we can still learn a lot from the system today,” says Heck. Just a few years ago researchers discovered a similar process in our red blood cells. “Cyanobacteria are the first organisms that have produced oxygen. Oxygen enrichment was the foundation for today's life. With the results of this study, we are learning about the biological primal mechanisms of life, but we can pursue specific aspects directly in clinical research,” Heck summarizes.

Original publication:

J. Snijder, J.M. Schuller, A. Wiegard, P. Lössl, N. Schmelling, I.M.Axmann, J.M. Plitzko, F. Förster and A.J.R. Heck: Structures of the cyanobacterial circadian oscillator frozen in a fully assembled state, Science, March 2017

Contact:

Prof. Dr. Jürgen Plitzko

Department Structural Biology

Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry

Am Klopferspitz 18

82152 Martinsried

E-Mail: plitzko@biochem.mpg.de

www.biochem.mpg.de/baumeister

Dr. Christiane Menzfeld

Public Relations

Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry

Am Klopferspitz 18

82152 Martinsried

Germany

Tel. +49 89 8578-2824

E-Mail: pr@biochem.mpg.de

www.biochem.mpg.de

http://www.biochem.mpg.de/en – homepage max planck institute of biochemistry