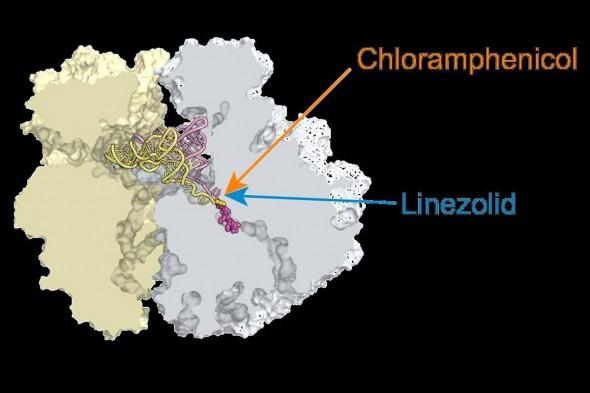

Chloramphenicol, linezolid stall ribosomes at specific mRNA locations.

Credit: Alexander Mankin, UIC

Ribosomes are among the most complex components in the cell, responsible for churning out all the proteins a cell needs for survival. In bacteria, ribosomes are the target of many important antibiotics.

The team of Alexander Mankin and Nora Vazquez-Laslop has conducted groundbreaking research on the ribosome and antibiotics. In their latest study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they found that while chloramphenicol and linezolid attack the catalytic center of the ribosome, they stop protein synthesis only at specific checkpoints.

“Many antibiotics interfere with the growth of pathogenic bacteria by inhibiting protein synthesis,” says Mankin, director of the UIC Center for Biomolecular Sciences and professor of medicinal chemistry and pharmacognosy. “This is done by targeting the catalytic center of the bacterial ribosome, where proteins are being made. It is commonly assumed that these drugs are universal inhibitors of protein synthesis and should readily block the formation of every peptide bond.”

“But — we have shown that this is not necessarily the case,” said Vazquez-Laslop, research associate professor of medicinal chemistry and pharmacognosy.

A natural product, chloramphenicol is one of the oldest antibiotics on the market. For decades it has been useful for many bacterial infections, including meningitis, plague, cholera and typhoid fever.

Linezolid, a synthetic drug, is a newer antibiotic used to treat serious infections — streptococci and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), among others — caused by Gram-positive bacteria that are resistant to other antibiotics. Mankin's previous research established the site of action and mechanism of resistance to linezolid.

While the antibiotics are very different, they each bind to the ribosome's catalytic center, where they were expected to inhibit formation of any peptide bond that links the components of the protein chain into a long biopolymer. In simple enzymes, an inhibitor that invades the catalytic center simply stops the enzyme from doing its job. This, Mankin said, had been what scientists had believed was also true for antibiotics that target the ribosome.

“Contrary to this view, the activity of chloramphenicol and linezolid critically depends on the nature of specific amino acids of the nascent chain carried by the ribosome and by the identity of the next amino acid to be connected to a growing protein,” Vazquez-Laslop said. “These findings indicate that the nascent protein modulates the properties of the ribosomal catalytic center and affects binding of its ligands, including antibiotics.”

Combining genomics and biochemistry has allowed the UIC researchers to better understand how the antibiotics work.

“If you know how these inhibitors work, you can make better drugs and make them better tools for research,” said Mankin. “You can also use them more efficiently to treat human and animal diseases.”

###

James Marks, Krishna Kannan, Emily Roncase, Dorota Klepacki, Amira Kefi and Cedric Orelle, all of UIC, are co-authors on the publication. The research was funded by National Institutes of Health grant AI 125518.