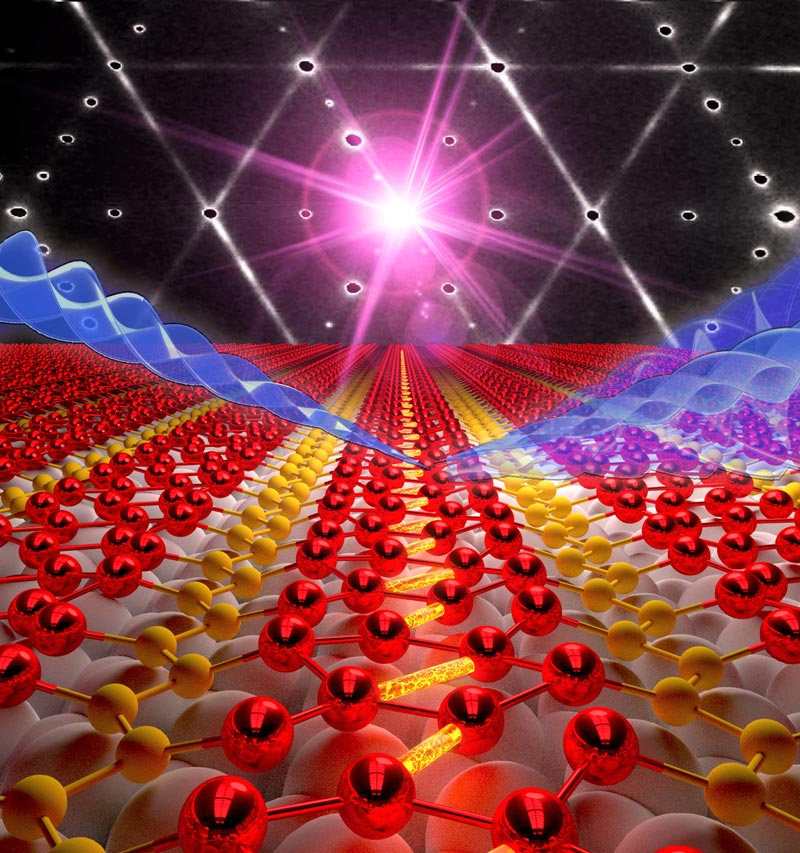

Electron beam (blue) which probes the structural change of the indium atom chains (red balls) upon excitation through a femtosecond laserpuls (violet). (Source: Dr. Andreas Lücke, Universität Paderborn)

Everything that surrounds us in our everyday life is three-dimensional, no matter how small: salt crystals, pollen, dust – even aluminium foil has a certain thickness. The first truly two-dimensional material graphene, was first discovered just 15 years ago, and ever since it has been used in applications such as transparent displays due to its outstanding electronic properties.

Now, scientists are recognising the potential of one-dimensional systems: systems comprising a string of atoms lined up like pearls on a necklace. These wires, the thinnest in the world, are unstable, a fascinating effect which is not at all well investigated – a fact that Dr. Tim Frigge, working within Prof. Michael Horn-von Hoegen’s research group, set out to address.

Frigge’s sample consisted of two single chains of indium atoms on a silicon substrate. At temperatures above approximately -140°C, the atoms form long chains, making the system metallic and enabling the conduction of electricity. Below this temperature, however, the atoms slip together in pairs and form hexagons, turning the system into an insulator.

This transition takes place at lightning-speed, within just 350 femtoseconds. In order to study it, the researchers had to induce the process artificially, doing so several million times at a rate of 5000 times per second. In order to achieve this, they stimulated the material with an ultrashort laser pulse, which, despite the icy temperatures of around -243°C, triggered the transition into the chain-shaped metallic state that otherwise only occurs at higher temperatures. The system subsequently reverted back to its non-metallic state one atom after the other, like a row of falling dominos.

In order to observe this transition, the physicists shot an electron beam across their sample, using its diffraction to determine the position of the atoms. Taking such a diffraction image every 50 femtoseconds results in a kind of ‘molecular movie’: a film that shows the path of the atoms over the sample surface – ‘just like in a flip-book,’ Frigge explains.

The researchers’ atomic level film represents the first step towards understanding – and, if possible, controlling – one-dimensional systems. It is worth noting, too, that as well as the path of the atoms, their speed can also be measured: over the short distance, the atoms hit speeds of around 100 km/h – and this in tiny fractions of a second, boasting acceleration trillions of times higher than that of a Porsche.

Original publication: Frigge et al., Optically excited strutural transition in atomic wires at the quantum limit, Nature, doi: 10.1038/nature21432

Further information:

Prof. Dr. Michael Horn-von Hoegen, Physics Faculty, 0203 379-1438, horn-von-hoegen@uni-due.de

Editor: Birte Vierjahn, 0203/ 379-8176, birte.vierjahn@uni-due.de