Brain imaging study sheds light on inner workings of human intelligence

People with higher fluid intelligence use specific brain regions to help focus their attention and resist distraction during a difficult mental task. <br>

Human intelligence is like a mental juggling act in which the smartest performers use specific brain regions to resist distraction and keep attention focused on critical pieces of information, according to a new brain imaging study from Washington University in St. Louis.

“Some people seem to perform better than others in novel, mentally-demanding situations, but why?” asks Jeremy R. Gray, Ph.D., co-author of the study to be posted Feb. 18 in an advance online issue of the journal Nature Neuroscience. “Presumably, people are using their brains differently, but how? “

Curious about the specific cognitive and neural mechanisms that underlie individual differences in intelligence, Gray and colleagues devised a study to explore the inner workings of one important aspect of human intelligence. The study sought to better understand the process through which the mind reasons and solves novel problems, an ability known among psychologists as “fluid intelligence.”

“The results may help researchers to understand the neural basis of individual differences in cognitive ability,” according to an embargoed news release issued this week by Nature Neuroscience.

Describing the study as “impressive” in part because of its relatively large number of participants, the journal suggests the findings “will help to constrain theories of the neural mechanisms underlying differences in general intelligence.”

The scientific team included Gray, a research scientist in psychology, and Todd S. Braver, Ph.D., an assistant professor in psychology, both in Arts & Sciences at Washington University; and Christopher F. Chabris, Ph.D., a research associate at Harvard University.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), the researchers measured subtle changes in brain activity as study participants performed a challenging mental task — one perhaps analogous to trying to drive to a new destination and attempting to keep the directions in mind while maintaining a conversation with passengers in the car.

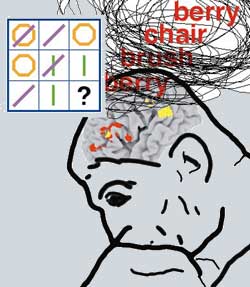

Participants in the study were asked to do what might seem like a mental juggling act. They had to keep a list of three words or faces actively in mind. Every few seconds, they had to add another word or face to this list, and drop the oldest item from the list. But before they forgot the old item completely, they had to indicate whether the new item they were adding exactly matched the oldest item they were dropping. Their brain activity was monitored as they did so.

Critically, the experimenters would occasionally throw participants a curve ball: showing them a new item that did not match the oldest item, but did match one nearby in the on-going sequence. Participants found these ’lure’ items to be especially distracting.

A key finding of the study was that participants with higher fluid intelligence were better able to respond correctly despite the interference from the ’lure’ items and they appeared to do so by engaging several key brain regions more strongly, including the prefrontal and parietal cortex.

“Our study depended on the fact that people vary in their intelligence level,” Braver said. “We used that variation to identify which brain regions are more critical for fluid intelligence.”

Several previous studies have examined how the brain responds to questions that appear on intelligence tests. However, the previous studies did not examine how people differ, nor what aspects of the test questions were most sensitive to such differences.

The findings in this Nature Neuroscience report draw on a cognitive theory of fluid intelligence proposed by Randall Engle, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology at Georgia Institute of Technology, and his colleagues. In this theory, the ability to resist or overcome interference like that on the ’lure’ trials is important.

“Imagine trying to keep a new phone number in mind just long enough to dial it,” suggests Gray. “Now imaging trying to do this while people around you are having a very interesting conversation. Paying attention to the conversation would interfere with remembering the phone number. People with higher fluid intelligence should have an easier time resisting being distracted by the conversation and keeping attention focused on the phone number.”

The Washington University study included 48 participants, all healthy, right-handed, native English speakers between the ages of 18 and 37, about half men and half women. Each participant was administered a standard test of fluid intelligence, known as Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices. Each participant was then asked to perform the word and face “mental juggling” tasks while lying inside an fMRI scanner. Each task tested a kind of short-term memory known as “working memory.”

To get a sense of how the task works, ask a friend to read the following words to you at a rate of about one word every 2.5 seconds: dog, cat, chair, table, cat, door, chair, dog.

For each word that you hear, make a mental note of whether it is the same word as you heard three words previously. That is, compare the fourth word you hear to the first, the fifth word to the second, and so on. (For the first three words, there is nothing to compare them to, so just remember them for later.)

The participants in the study had to do a similar task, except that it involved viewing a series of either unrelated words or unfamiliar faces on a computer screen, one word or face every few seconds. Participants had to press a button to indicate whether or not the word or face on the screen matched one shown exactly three previously.

The task is challenging, but the researchers included some especially tricky “lure” items that were even more difficult. These were words or faces that had been shown two, four, or five previously in the sequence, but not three previously.

For example, the second time the word “chair” appears in the list above is a lure. The lure items are easily confusable for an item seen three previously. The mere fact that the word or face was seen recently is salient and hard to ignore. This creates interference of the type that, according to Engle and colleagues, should engage fluid intelligence.

On the task, people with higher fluid intelligence were generally more accurate than those with lower fluid intelligence.

Fluid intelligence appeared to be most critical for performance on lure trials. The critical nature of lure trials also was reflected in brain activation differences between individuals of high and low fluid intelligence. In several brain areas including prefrontal and parietal cortex, people with higher fluid intelligence had stronger neural activity than people with lower fluid intelligence. That is, doing the task led to widespread activity across the brain, but the strength of this activity was related to fluid intelligence only on the lure trials.

So, what is it exactly that the participants with higher fluid intelligence were doing differently on the lure trials? Their performance suggests they were keeping the distracting information at bay, and they appeared to do so by activating regions in prefrontal and parietal cortex, as well as a number of auxiliary regions.

While the study offers new insight into fluid intelligence, the researchers emphasize that how well people perform in a given situation depends on the complex interaction of many abilities. For example, this study does not address every aspect of fluid intelligence, nor does it account for other forms of intelligence, such as crystallized intelligence, which involves specific skills and expertise. Motivation and emotion are also important. Other work suggests that fluid intelligence may not be fixed, but can be increased.

“I find this study exciting in part because it opens a door to doing many further studies that capitalize on differences in psychological functions among individuals,” added Braver. “Individuals differ in cognitive abilities and in many other ways as well, such as personality. We can use this same type of approach to understand how these psychological differences are reflected in brain function.”

Advance Online Publication: This paper, titled “Neural mechanisms of general fluid intelligence” is scheduled for Advance Online Publication (AOP) on Nature Neuroscience’s website on Feb. 18. The AOP version of the article can be considered definitive; the only difference from the subsequent print version is that AOP articles are published before they have been assigned an issue/volume/page number. Papers published online before they have been allocated to a print issue will be citable via a digital object identifier (DOI) number. The DOI for this paper will be 10.1038/Nn1014.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.wustl.edu/All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

First-of-its-kind study uses remote sensing to monitor plastic debris in rivers and lakes

Remote sensing creates a cost-effective solution to monitoring plastic pollution. A first-of-its-kind study from researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities shows how remote sensing can help monitor and…

Laser-based artificial neuron mimics nerve cell functions at lightning speed

With a processing speed a billion times faster than nature, chip-based laser neuron could help advance AI tasks such as pattern recognition and sequence prediction. Researchers have developed a laser-based…

Optimising the processing of plastic waste

Just one look in the yellow bin reveals a colourful jumble of different types of plastic. However, the purer and more uniform plastic waste is, the easier it is to…