Sensor of bacteria and viruses on high alert at the site of action

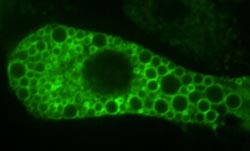

This immune cell produces TLR9, which glows green when irradiated with laser light. The molecule is localized on the edge of tiny spheres within the cell, where it will ultimately encounter pathogenic DNA.<br><br>HZI/Oelkers<br>

“Danger!” signals TLR9, the molecular sensor, whenever it recognizes bacterial or viral genetic information, specifically DNA. Instantly, the immune system initiates the process of fighting off the infection.

This initial protective mechanism is very fast because it focuses on recognition of basic structural properties – in this case bacterial or viral DNA. Now, researchers at the Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI) have shown that TLR9 not only quickly recognizes DNA, it also waits, ready for action, right at the site where it will encounter it.

It is through mechanisms like these that we gain valuable time before acquired immunity, the more effective but much slower branch of the immune system, is activated. Together with their German, US, and South Korean colleagues, HZI scientists have examined what the requirements for TLR9 function are in different kinds of immune cells. The researchers have now published their findings in “The Journal of Immunology”, which has ranked this research among the top ten percent of the scientific journal's total published contributions.

The scientists expect that their insights might be exploited for therapeutic purposes. “In addition to its classic job, TLR9 could potentially help with disease prevention. One option, which is currently under investigation in clinical studies, is adding DNA to vaccines – to switch on TLR9 and thereby activate the immune system more strongly,” explains Prof. Melanie Brinkmann, head of HZI's Viral Immune Modulation research group. In other instances it may make sense to inhibit this molecule – as in those cases where it erroneously recognizes the body's own DNA, causing autoimmune diseases. “In order to fully grasp the potential of this and similar molecules, we need to better understand how TLR9 functions in immune cells,” explains Brinkmann. The researchers are especially interested in figuring out how the molecule gets from the location within the cell where it is produced into the endolysosomes. It is inside these tiny bubbles that it ultimately encounters the DNA of invading bacteria or viruses.

To trace TLR9's movements within the cell, the researchers developed a murine model, in which mice produced a color-labeled version of the protein. With the help of a microscope, the scientists were able to localize TLR9 inside different immune cells, revealing how it is capable of such a rapid response. Prior to a bacterial or viral infection, the sensor migrates into the endolysosomes to “await” potential intruders. By thus positioning TLR9, the cell ensures a given pathogens' rapid detection.

In order to be fully operational, a portion of the protein must first be cleaved off – this is done by “molecular scissors”, which the researchers identified as well. Both transport into the endolysosomes and cleavage of the protein depend upon the presence of a second protein called UNC93B1. “We thus managed to identify a number of important components that are key to TLR9's ability to recognize bacterial and viral intruders and set off an alarm,” says Dr. Margit Oelkers, another HZI scientist involved in the project. Studying TLR9's transport within different immune cell types, the researchers found out that the process actually varies from one cell type to the next. Says Brinkmann: “The results are helping us better understand how TLR9 works. Our findings are critical if we are to exploit the molecule's properties for therapeutic purposes.”

Original publication

Ana M. Avalos, Oktay Kirak, J. Margit Oelkers, Marina C. Pils, You-Me Kim, Matthias Ottinger, Rudolf Jaenisch, Hidde L. Ploegh und Melanie M. Brinkmann

Cell-Specific TLR9 Trafficking in Primary APCs of Transgenic TLR9-GFP Mice

The Journal of Immunology 2013 190:695-702

Ideally, our immune system will recognize and subsequently eliminate pathogens that enter our bodies. However, many microorganisms and viruses have evolved strategies to evade immune detection. The “Viral Immune Modulation” research group seeks to uncover the different mechanisms that particularly herpes viruses use to perform this feat.

The Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research (HZI):

The Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research contributes to the achievement of the goals of the Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres and to the successful implementation of the research strategy of the German Federal Government. The goal is to meet the challenges in infection research and make a contribution to public health with new strategies for the prevention and therapy of infectious diseases.

http://www.helmholtz-hzi.de/en

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Innovative 3D printed scaffolds offer new hope for bone healing

Researchers at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia have developed novel 3D printed PLA-CaP scaffolds that promote blood vessel formation, ensuring better healing and regeneration of bone tissue. Bone is…

The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease

ASU- and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute-led study implicates link between a common virus and the disease, which travels from the gut to the brain and may be a target for antiviral…

Molecular gardening: New enzymes discovered for protein modification pruning

How deubiquitinases USP53 and USP54 cleave long polyubiquitin chains and how the former is linked to liver disease in children. Deubiquitinases (DUBs) are enzymes used by cells to trim protein…