Can the canine distemper virus infect humans?

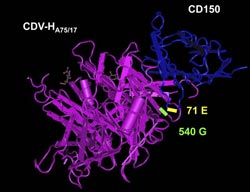

The structural model shows how, after just one mutation, an envelope protein (pink) of the canine distemper virus can bind to the CD150 receptor (blue) of human immune cells. This would give the virus access to the cell interior.<br>Graphic: Bieringer et al. PLoS ONE 8(3): e57488<br>

Every year, 20 to 30 million people worldwide contract measles. This viral infection is sometimes regarded as a “harmless childhood disease” – but that is not the case. In 2010 alone, 150,000 people died from it. The disease can also lead to serious secondary ailments: blindness caused by measles affects around 30,000 people a year, mainly in Africa.

It is no wonder that the World Health Organization (WHO) wants to eradicate measles, like it managed to do with smallpox in 1980. “This goal could be achieved as early as 2020 if the entire global population was systematically vaccinated against measles,” says Jürgen Schneider-Schaulies, a professor at the University of Würzburg’s Institute of Virology and Immunobiology.

If measles were to be defeated one day, there would be no more need for immunizations. But other viruses very closely related to measles could then exploit the lack of protection provided by immunization and take its place – canine distemper, for example. This viral disease affects dogs and other animals, causing ailments such as diarrhea, seizures, and brain damage. The infection is often fatal.

Does the measles vaccination protect against canine distemper?

“If dogs are given the measles vaccine, they are protected against infection with the distemper virus,” says Schneider-Schaulies. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that people who have been vaccinated against measles, or who have survived measles, are also immune to distemper viruses. In fact, there are no known cases to date of humans becoming infected with distemper.

Yet the path to humans does not seem all that lengthy. Unlike the measles virus, which only has humans as its natural host, canine distemper viruses can infect various carnivorous animals: dogs, foxes, raccoons, badgers, lions and even monkeys (macaques). “In this respect, the canine distemper virus is much more flexible than the measles virus,” says the Würzburg virologist, “and with genetic mutations it could also become infectious to humans.”

In viruses, the genetic material mutates very quickly, as demonstrated by the influenza viruses. These vary so dramatically that the immune system constantly reacts to them anew and the vaccine has to be adjusted afresh every year – and yet there are still regular flu epidemics.

First infection stage already achieved

How much would the canine distemper virus have to change in order to be able to infect humans? This question has been examined by the research team led by Schneider-Schaulies using the initial stages of infection, binding to receptors.

The virus can already bind to one of the two receptors, nectin-4 on epithelial cells, without any mutation. It ought to be easy for the virus to bind to the other receptor: all it requires to access immune cells via the CD150 receptor is a single mutation in the viral envelope protein hemagglutinin. This is reported by the Würzburg virologists and their colleagues from the University of Berne in the journal PLoS ONE.

Several mutations needed for adaptation to humans

However, this will merely enable the canine distemper virus to smuggle its way into the cells. “Once inside, it will require several more changes in its genes if it is to be able to reproduce successfully there and cause harm,” explains Schneider-Schaulies. Full adaptation to humans is therefore not quite so simple.

“As long as a high percentage of the population is immune to measles, we probably do not need to worry much about the canine distemper virus making the transition to humans,” predicts the Würzburg researcher. However, he says, the science world really ought to start thinking about one thing: what the best action would be to take against the canine distemper virus if measles should happen to be eradicated.

Bieringer, M., Han, W.J., Kendl, S., Khosravi, M., Plattet, P., and Schneider-Schaulies, J. (2013): Experimental adaptation of canine distemper virus (CDV) to the human entry receptor CD150. PLoS ONE 8(3): e57488. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057488

The article in PLoS ONE: http://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057488

Contact

Prof. Dr. Jürgen Schneider-Schaulies, Institute of Virology and Immunobiology at the University of Würzburg, T +49 (0)931 31-81564, jss@vim.uni-wuerzburg.de

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

First-of-its-kind study uses remote sensing to monitor plastic debris in rivers and lakes

Remote sensing creates a cost-effective solution to monitoring plastic pollution. A first-of-its-kind study from researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities shows how remote sensing can help monitor and…

Laser-based artificial neuron mimics nerve cell functions at lightning speed

With a processing speed a billion times faster than nature, chip-based laser neuron could help advance AI tasks such as pattern recognition and sequence prediction. Researchers have developed a laser-based…

Optimising the processing of plastic waste

Just one look in the yellow bin reveals a colourful jumble of different types of plastic. However, the purer and more uniform plastic waste is, the easier it is to…