Electricity that comes from noise

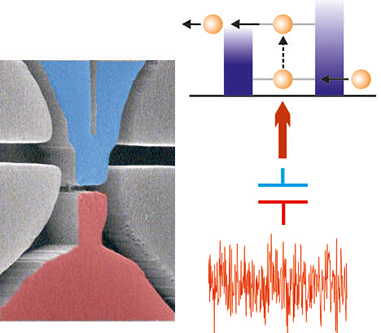

A new development by Würzburg physicists can produce a rectified current from differences in temperature. This means, for example, that sensor networks can be supplied with energy. Graphic: Fabian Hartmann

The smaller and more powerful that computer chips are the more heat they produce. This causes financial problems, because cooling costs money.

For this reason, Google is keen to build new server farms in northern latitudes, such as Finland, where the Arctic cold keeps the servers at low temperatures virtually by itself. Excessive heat generation imposes limits on progressive miniaturization, making it difficult to develop even smaller and more powerful processors.

Publication in Physical Review Letters

The fact that this energy could be used in a special way to produce electricity was foreseen theoretically by physicists from the University of Geneva a few years ago. Now, a team of physicists at the University of Würzburg have succeeded in translating this theory into practice.

Scientists at the Department of Applied Physics under Professor Lukas Worschech and Professor Sven Höfling have created a component that is capable of producing a rectified current from differences in temperature. The scientists have presented their work in the journal Physical Review Letters.

“With our component we generate energy from random movements,” says Dr. Fabian Hartmann to explain the underlying principle. In this case, this involves movements of electrons in structures that are only a few billionths of a meter in size. The greater the fluctuations in this structure, the more intense the random movements are – the physicist speaks of “noise”. “Where the heat is great we find a high level of noise. In colder areas the noise is lower,” explains Hartmann. The trick now is to produce a rectified current from this difference.

A two-dimensional electron gas

At the Gottfried-Landwehr-Laboratory for Nanotechnology at the University of Würzburg, the physicists “created” a structure referred to in the technical jargon as a “quantum dot”. This involved building an aluminum gallium arsenide heterostructure in layers on a carrier material that is only a few micrometers in size. Then onto this there they etched special structures in which electrons can move around.

However, the gap that offers the electrons room is only a few nanometers wide. This therefore creates a two-dimensional electron gas in which the directions of movement are heavily restricted. “In doing this we achieve very high electron mobility in a defined area without scattering processes,” is how Hartmann outlines the result. If you then bring two of these quantum dots of different temperatures close together, this produces the desired effect: Random movement, high-level noise on one side, generates directed movement on the other – a direct current.

Better than thermoelectric elements

It was, of course, already possible to generate energy from differences in temperature in the form of electricity. “Thermoelectric elements,” as they are called, are capable of this. The spectrum of possibilities ranges from the wristwatch, which receives its drive energy from the small difference in temperature between ambient air and body heat, to thermoelectric units, which use waste heat from a combustion process, and all the way through to the space probe Cassini, which converts the decay heat of Plutonium-238 into electrical energy.

However, the physicists believe that thermoelectric elements have a serious disadvantage: “With them, heat flow and electrical current are rectified,” explains Fabian Hartmann. This means that while they produce electricity, these materials automatically reduce the difference in temperature until the difference has disappeared. As a result, electricity can no longer flow.

“With our construction elements, on the other hand, these two processes are made independent of one another. The differences in temperature are therefore easier to maintain,” says Hartmann.

Low energy efficiency with potential

The energy efficiency of the components sounds to the layman like it is barely anything. Around 20 picowatts is the power from such an element, says the physicist. 50 billion of them generate as much as one watt. Is the development of these parts, therefore, just a gimmick in the laboratory?

Absolutely not, says Hartmann. For one thing, a common processor already has more than one billion transistors, which all produce heat. For another, it is one of the goals of his work to supply autonomous sensor networks with energy in this manner! And only a few microwatts were needed to achieve this.

Voltage Fluctuation to Current Converter with Coulomb-Coupled Quantum Dots. F. Hartmann, P. Pfeffer, S. Höfling, M. Kamp, and L. Worschech. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.146805

Contact

Dr. Fabian Hartmann, Department of Applied Physics, T: +49 (0)931 31-88579, e-mail: fhartmann@physik.uni-wuerzburg.de

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.uni-wuerzburg.deAll latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

NASA: Mystery of life’s handedness deepens

The mystery of why life uses molecules with specific orientations has deepened with a NASA-funded discovery that RNA — a key molecule thought to have potentially held the instructions for…

What are the effects of historic lithium mining on water quality?

Study reveals low levels of common contaminants but high levels of other elements in waters associated with an abandoned lithium mine. Lithium ore and mining waste from a historic lithium…

Quantum-inspired design boosts efficiency of heat-to-electricity conversion

Rice engineers take unconventional route to improving thermophotovoltaic systems. Researchers at Rice University have found a new way to improve a key element of thermophotovoltaic (TPV) systems, which convert heat…