Constricting without a string: Bacteria gone to the worms divide differently

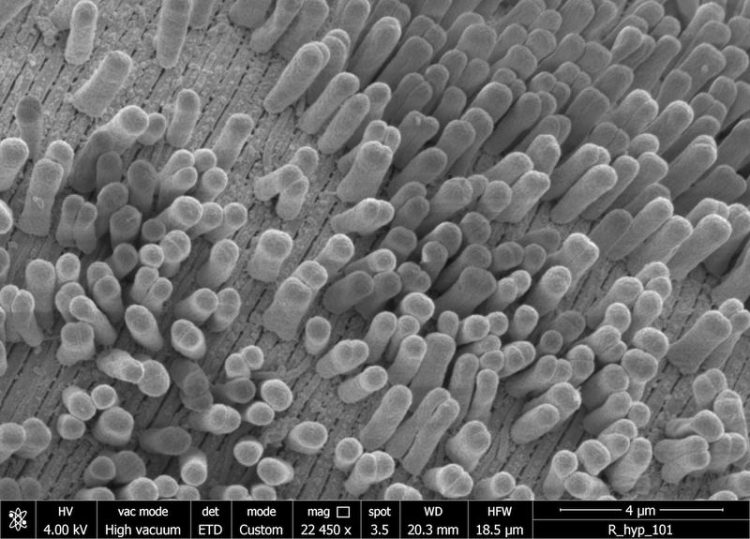

The rod-shaped bacteria densely populating the surface of the worm belong to the Gammaproteobacteria. These comprise members of our gut microbiome but also some serious pathogens. Nikolaus Leisch

Even though the diversity and importance of microorganisms in all ecosystems has been established long time ago, our knowledge in many areas of microbiology is still limited. One of those areas is bacterial cell division, detailing how cells reproduce, creating two daughter cells from one. One of the key proteins involved in this process is FtsZ. Like a rubber band, FtsZ creates a ring around the cell and virtually pinches it off, thus initiating cell division. That’s the theory, according to the current state of knowledge. But things can be quite different, as the study on hand shows.

“Nearly all research on this topic was done on a handful of model organisms which can be cultivated in the lab”, explains first author Niko Leisch from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen. As a result, many aspects of microbial life remain undiscovered. Leisch, together with the lead scientist Silvia Bulgheresi from the University of Vienna and Tanneke den Blaauwen from the University of Amsterdam, therefore uses organisms that cannot be cultivated in the laboratory. They study bacteria which live as symbionts on the surface of a small nematode. The worm lives in a symbiosis with only a single species of bacteria, which form a dense but highly organized “coat” on the surface of the worm. That’s why, using these worms, we can study pure cultures from the environment”, Leisch explains the “trick”.

The bacterium in question divides longitudinally, which is already highly unusual for a rod-shaped bacterium. On top of that, the scientists found out that the bacteria divide asymmetrically. The division process starts where the cell touches the worm. The cell pole which is directed towards the environment subsequently follows.

„Microbiology textbooks tell us that bacterial cells assemble a ring of FtsZ before division”, Leisch continues. “Despite using high-resolution microscopic approaches with specific dyes, we couldn’t find this ring.” FtsZ was present, but the proteins only accumulated as small patches along the length axis. “As no ring is formed, these patches of FtsZ must individually exert a force to divide the cell. This has so far not been observed and gives rise to many new questions. For example, how is the necessary force generated to divide the cell?”

Why all of this matters? “The majority of what we know nowadays about bacteria, their growth and reproduction comes from the work from cultivable model organisms”, says Leisch. “But especially the work on bacteria from the environment done in the last few years has shown again and again how the cell division machinery is much more flexible and complex than what we though. And a better understanding of growth and division of bacteria are crucial for the development of potential new antibiotics.”

The scientists suspect that the worm on which the bacteria live influences their cell division. It seems to control its symbiotic residents quite well. For example, it somehow manages to keep its head and tail clear of the otherwise dense coat of bacteria. “We still don’t know how it does that”, says Leisch.

“Resistance to antibiotics is a big issue nowadays. The development of new antibiotics aims towards inhibiting growth and reproduction of bacteria. This worm obviously manages to do just that. If we can understand how it accomplishes that, it would be a great step forward.”

The unusual cell division of this bacterium is probably an adaptation to the symbiotic lifestyle, Leisch and his colleagues suspect. But to better understand the processes and their importance they emphasize that more studies need to be performed on such non-model organisms.

Original publication

Nikolaus Leisch, Nika Pende, Philipp M. Weber, Harald R. Gruber-Vodicka, Jolanda

Verheul, Norbert O. E. Vischer, Sophie S. Abby, Benedikt Geier, Tanneke den Blaauwen and Silvia Bulgheresi: Asynchronous division by non-ring FtsZ in the gammaproteobacterial symbiont of Robbea hypermnestra. Nature Microbiology.

DOI: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.182

Participating institutes

Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Celsiusstrasse 1, 28359 Bremen, Germany

University of Vienna, Department of Ecogenetics and Systems Biology, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria

Bacterial Cell Biology, Swammerdam Institute of Life Sciences, University of Amsterdam, Boelelaan 1108, 1081 HZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Please direct your queries to

Dr. Nikolaus Leisch

Phone: +49 421 2028 822

E-Mail: nleisch(at)mpi-bremen.de

or the press office

Dr. Fanni Aspetsberger

Dr. Manfred Schlösser

Phone: +49 421 2028 704

E-Mail: presse(at)mpi-bremen.de

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

A ‘language’ for ML models to predict nanopore properties

A large number of 2D materials like graphene can have nanopores – small holes formed by missing atoms through which foreign substances can pass. The properties of these nanopores dictate many…

Clinically validated, wearable ultrasound patch

… for continuous blood pressure monitoring. A team of researchers at the University of California San Diego has developed a new and improved wearable ultrasound patch for continuous and noninvasive…

A new puzzle piece for string theory research

Dr. Ksenia Fedosova from the Cluster of Excellence Mathematics Münster, along with an international research team, has proven a conjecture in string theory that physicists had proposed regarding certain equations….