Nanotubes go with the flow to penetrate brain tissue

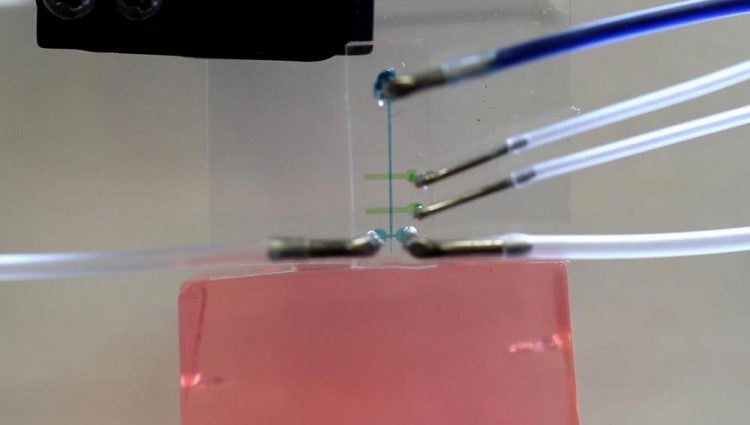

A microfluidic device delivers a carbon nanotube fiber into agarose, a lab experiment stand-in for brain tissue. The device could provide a gentler method to implant wires into patients with neurological diseases and help scientists explore cognitive processes and develop implants to help people to see, to hear and to control artificial limbs. Credit: Robinson Lab/Rice University Usage Restrictions: For news reporting purposes only.

Rice University researchers have invented a device that uses fast-moving fluids to insert flexible, conductive carbon nanotube fibers into the brain, where they can help record the actions of neurons.

The Rice team's microfluidics-based technique promises to improve therapies that rely on electrodes to sense neuronal signals and trigger actions in patients with epilepsy and other conditions.

Eventually, the researchers said, nanotube-based electrodes could help scientists discover the mechanisms behind cognitive processes and create direct interfaces to the brain that will allow patients to see, to hear or to control artificial limbs.

The device uses the force applied by fast-moving fluids that gently advance insulated flexible fibers into brain tissue without buckling. This delivery method could replace hard shuttles or stiff, biodegradable sheaths used now to deliver wires into the brain. Both can damage sensitive tissue along the way.

The technology is the subject of a paper in the American Chemical Society journal Nano Letters.

Lab and in vivo experiments showed how the microfluidic devices force a viscous fluid to flow around a thin fiber electrode. The fast-moving fluid slowly pulls the fiber forward through a small aperture that leads to the tissue. Once it crosses into the tissue, tests showed the wire, though highly flexible, stays straight.

“The electrode is like a cooked noodle that you're trying to put into a bowl of Jell-O,” said Rice engineer Jacob Robinson, one of three project leaders. “By itself, it doesn't work. But if you put that noodle under running water, the water pulls the noodle straight.”

The wire moves slowly relative to the speed of the fluid. “The important thing is we're not pushing on the end of the wire or at an individual location,” said co-author Caleb Kemere, a Rice electrical and computer engineer who specializes in neuroscience. “We're pulling along the whole cross-section of the electrode and the force is completely distributed.”

“It's easier to pull things that are flexible than it is to push them,” Robinson said.

“That's why trains are pulled, not pushed,” said chemist Matteo Pasquali, a co-author. “That's why you want to put the cart behind the horse.”

The fiber moves through an aperture about three times its size but still small enough to let very little of the fluid through. Robinson said none of the fluid follows the wire into brain tissue (or, in experiments, the agarose gel that served as a brain stand-in).

There's a small gap between the device and the tissue, Robinson said. The small length of fiber in the gap stays on course like a whisker that remains stiff before it grows into a strand of hair. “We use this very short, unsupported length to allow us to penetrate into the brain and use the fluid flow on the back end to keep the electrode stiff as we move it down into the tissue,” he said.

“Once the wire is in the tissue, it's in an elastic matrix, supported all around by the gel material,” said Pasquali, a carbon nanotube fiber pioneer whose lab made a custom fiber for the project. “It's supported laterally, so the wire can't easily buckle.”

Carbon nanotube fibers conduct electrons in every direction, but to communicate with neurons, they can be conductive at the tip only, Kemere said. “We take insulation for granted. But coating a nanotube thread with something that will maintain its integrity and block ions from coming in along the side is nontrivial,” he said.

Sushma Sri Pamulapati, a graduate student in Pasquali's lab, developed a method to coat a carbon nanotube fiber and still keep it between 15 to 30 microns wide, well below the width of a human hair. “Once we knew the size of the fiber, we fabricated the device to match it,” Robinson said. “It turned out we could make the exit channel two or three times the diameter of the electrode without having a lot of fluid come through.”

The researchers said their technology may eventually be scaled to deliver into the brain at once multiple microelectrodes that are closely packed; this would make it safer and easier to embed implants. “Because we're creating less damage during the implantation process, we might be able to put more electrodes into a particular region than with other approaches,” Robinson said.

###

Flavia Vitale, a Rice alumna and now a research instructor at the University of Pennsylvania, and Daniel Vercosa, a Rice graduate student, are lead authors of the paper. Co-authors are postdoctoral fellow Alexander Rodriguez, graduate students Eric Lewis, Stephen Yan and Krishna Badhiwala and alumnus Mohammed Adnan of Rice; postdoctoral researcher Frederik Seibt and Michael Beierlein, an associate professor of neurobiology and anatomy at McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston; and Gianni Royer-Carfagni, a professor of structural mechanics at the University of Parma, Italy.

Robinson and Kemere are assistant professors of electrical and computer engineering and adjunct assistant professors at Baylor College of Medicine. Pasquali is a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering, of materials science and nanoengineering and of chemistry and chair of Rice's Department of Chemistry.

Supporting the research are the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the Welch Foundation, the National Science Foundation, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the American Heart Association, the National Institutes of Health and the Citizens United for Research in Epilepsy Taking Flight Award.

Read the abstract at http://pubs.

This news release can be found online at http://news.

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews

Video: Rice University researchers attempt to insert a carbon nanotube fiber into agarose, a model for brain tissue, without support; it buckles without penetrating the surface. With a test microfluidic device, they successfully insert a 30-micron carbon nanotube fiber into agarose. The fiber passes through a small gap between the device and the agarose, penetrates the surface and continues to extend into the target. (Credit: Rice University) https:/

Video: A second video shows the completed microfluidic device inserting a carbon nanotube fiber into agarose. (Credit: Daniel Vercosa/Rice University) https:/

Related materials:

Carbon nanotube fibers make superior links to brain: http://news.

Spinning nanotube fibers at Rice University: https:/

Robinson Lab: http://www.

Kemere Lab: http://rnel.

Complex Flows of Complex Fluids (Pasquali Lab): https:/

George R. Brown School of Engineering: https:/

Wiess School of Natural Sciences: http://natsci.

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation's top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,879 undergraduates and 2,861 graduate students, Rice's undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for quality of life and for lots of race/class interaction and No. 2 for happiest students by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger's Personal Finance. To read “What they're saying about Rice,” go to http://tinyurl.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

Innovative vortex beam technology

…unleashes ultra-secure, high-capacity data transmission. Scientists have developed a breakthrough optical technology that could dramatically enhance the capacity and security of data transmission (Fig. 1). By utilizing a new type…

Tiny dancers: Scientists synchronise bacterial motion

Researchers at TU Delft have discovered that E. coli bacteria can synchronise their movements, creating order in seemingly random biological systems. By trapping individual bacteria in micro-engineered circular cavities and…

Primary investigation on ram-rotor detonation engine

Detonation is a supersonic combustion wave, characterized by a shock wave driven by the energy release from closely coupled chemical reactions. It is a typical form of pressure gain combustion,…