In cystic fibrosis, lungs feed deadly bacteria

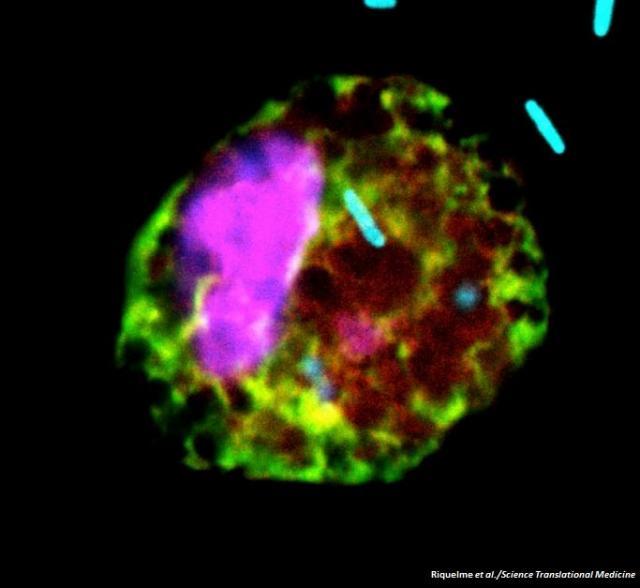

P. aeruginosa bacteria (blue) thrive in lungs that produce lots of succinate, a preferred food. Credit: Sebastián Riquelme, Columbia University Irving Medical Center

Why does P. aeruginosa, but not other common bacteria, thrive in cystic fibrosis lungs?

A new study from researchers at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons suggests the answer has to do with the bacterium's culinary preference for succinate, a byproduct of cellular metabolism, that is abundant in cystic fibrosis lungs.

“Preventing infection by P. aeruginosa could greatly improve the health of people with cystic fibrosis,” says Sebastián A. Riquelme, PhD, the study's lead author and a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Pediatrics. “And it's possible that we could control infection by targeting the bacteria's use of succinate in the lung.”

Excess Succinate in CF Lungs

The excess succinate in the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis comes from an interaction between two proteins, CFTR and PTEN. Mutations in the CFTR gene causes cystic fibrosis by preventing the CFTR protein from transporting ions in and out of cells. But the mutations also disrupt CFTR's interactions with PTEN (a discovery made by the Columbia team in 2017).

It is this abnormal PTEN-CFTR interaction, the new study found, that causes lung cells to release an excessive amount of succinate. The succinate fueled growth of P. aeruginosa in the lungs of mice, but had no effect on Staphylococcus aureus, another major pathogen.

More Succinate, More Slime

Not only does P. aeruginosa thrive in a succinate-rich environment, it actively adapts to the abundance of its favored food.

“Succinate-adapted bacteria divert their metabolism into the production of extracellular slime that makes the organisms extremely difficult to eradicate from the lung,” says the study's senior author Alice Prince, MD, the John M. Driscoll Jr., MD and Yvonne Driscoll, MD Professor of Pediatrics. “These bacteria are the cause of chronic infection in cystic fibrosis.”

The succinate-fed bacteria also suppress the immune response, furthering hampering the body's ability to control the infection.

Targeting Succinate

The new findings–made in mice and in human cells in tissue culture–suggest that it may be possible to treat P. aeruginosa infection by restoring the interaction between PTEN and CFTR, even if CFTR's other functions are impaired.

New drugs for cystic fibrosis, such as the lumacaftor and ivacaftor combination currently available, restore the CFTR-PTEN interaction and may decrease the generation of succinate.

Limiting the accumulation of succinate may also reduce bacterial growth and adaptation. Succinate is mainly produced by immune cells during the inflammatory response, Riquelme says. “We predict that by controlling the exaggerated inflammation observed in the airway, we could reduce succinate and P. aeruginosa infection.”

###

The study, “CFTR-PTEN-dependent mitochondrial metabolic dysfunction promotes Pseudomonas aeruginosa airway infection,” was published in July in Science Translational Medicine.

Additional authors: Carmen Lozano (Centro de Investigación Biomédica de la Rioja, Microbiología Molecular, Logroño, Spain), Ahmed M. Moustafa (University of Pennsylvania and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia), Kalle Liimatta (Columbia University Irving Medical Center), Kira L. Tomlinson (CUIMC), Clemente J. Britto (Yale University School of Medicine), Sara Khanal (Yale University School of Medicine), Simren K. Gill (CUIMC), Apurva Narechania (American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY), José M. Azcona-Gutiérrez (Hospital San Pedro, Logroño, Spain), Emily DiMango (CUIMC), Yolanda Saénz (Centro de Investigación Biomédica de la Rioja, Microbiología Molecular), and Paul J. Planet (University of Pennsylvania and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia).

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants R35HL135800, GG011557-26 to Columbia University Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, UL1TR001873, and S10RR027050); the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (pilot grant PLANET16I and postdoctoral fellowship RIQUEL 17F0/PG008837); an S.B. postdoctoral contract (CD15/00125); an M-AES mobility grant (MV16/00053); Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (St. Jude Award), Thrasher Research Fund (PG005871), Doris Duke Clinical Scientist Development Award (2012060), and a Louis V. Gerstner Scholar Award.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

The Department of Pediatrics at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons is a top ranked department nationally, with more than $20 million per year in research funding from the National Institutes of Health, and is the only pediatrics department in New York ranked in the top 25 by US News & World Report.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

A ‘language’ for ML models to predict nanopore properties

A large number of 2D materials like graphene can have nanopores – small holes formed by missing atoms through which foreign substances can pass. The properties of these nanopores dictate many…

Clinically validated, wearable ultrasound patch

… for continuous blood pressure monitoring. A team of researchers at the University of California San Diego has developed a new and improved wearable ultrasound patch for continuous and noninvasive…

A new puzzle piece for string theory research

Dr. Ksenia Fedosova from the Cluster of Excellence Mathematics Münster, along with an international research team, has proven a conjecture in string theory that physicists had proposed regarding certain equations….