X-ray double flashes control atomic nuclei

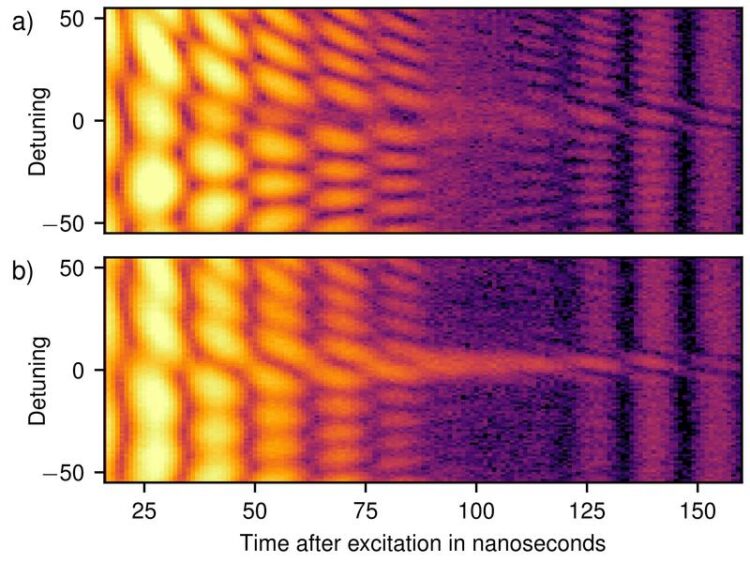

Fig. 2: Observed X-ray interference structures as a function of time (t) and detuning (δ) of the two samples against each other. (a) Measurement data for the case of excitation, (b) for the case of enhanced excitation.

Graphics: MPIK

A team of researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics in Heidelberg has coherently controlled nuclear excitations using suitably shaped X-ray light for the first time. In the experiment performed at the European Synchrotron ESRF, they achieved a temporal control stability of a few zeptoseconds. This forms the basis for new experimental approaches exploiting the control of nuclear dynamics which could lead to more precise future time standards and open new possibilities on the way to nuclear batteries. [Nature, 17 February 2021]

Graphics: MPIK

Modern experiments on quantum dynamics can control the quantum processes of electrons in atoms to a large extent by means of laser fields. However, the inner life of atomic nuclei usually plays no role because their characteristic energy, time and length scales are so extreme that they are practically unaffected by the laser fields. Fresh approaches breathe new life into nuclear physics by exploiting this insensitivity to external disturbances and using the extreme scales of the atomic nuclei for particularly precise measurements. Thus, atomic nuclei can respond to X-rays with an extremely well-defined energy by exciting individual nucleons – similar to electrons in the atomic shell. These transitions can be used as clockworks for precise nuclear clocks, and this requires the measurement of nuclear properties with the highest precision.

A team of researchers around physicists from the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics in Heidelberg has now gone a step forward by not only measuring the quantum dynamics of atomic nuclei, but also controlling them using suitably shaped X-ray pulses with previously unattained temporal stability of a few zeptoseconds – a factor of 100 better than anything previously achieved. This opens the toolbox of coherent control, which has been successfully established in optical spectroscopy, to atomic nuclei – providing completely new possibilities and perspectives.

So-called coherent control uses the wave properties of matter to control quantum processes via electromagnetic fields, e.g. laser pulses. In addition to the frequency or wavelength, each wave phenomenon is characterised by the amplitude (wave height) and phase (temporal position of wave crests and troughs). A simple analogy is the control of an oscillating swing by periodic, wave-like pushing. For this, the exact timing (phase) of the push relative to the swing motion has to be controlled. If the oncoming swing is pushed, it is decelerated. If, on the other hand, it moves away, its deflection is increased by the push.

Analogously, the quantum-mechanical properties of matter can be controlled via correspondingly precise steering of the applied laser fields. In the past decades, there has been great progress and success in the coherent control of atoms and molecules, with a temporal precision of light down to the attosecond range, the billionth part of a billionth of a second, which corresponds to the natural time scale of electrons in atoms. Important research goals with possible future applications are, for example, the control of chemical reactions or the development of new, more precise time standards.

In recent years, the availability of novel radiation sources for X-rays with laser quality (synchrotron radiation and free-electron lasers) has opened up a new field: nuclear quantum optics. Physicists from the departments of Christoph Keitel and Thomas Pfeifer at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics (MPIK) in Heidelberg have now succeeded for the first time in demonstrating coherent control of nuclear excitations by X-rays at the European Synchrotron ESRF (Grenoble, France) in cooperation with researchers from DESY (Hamburg) and the Helmholtz Institute/Friedrich Schiller University (Jena). A stability of the coherent control of a few zeptoseconds (a thousandth of an attosecond) was achieved.

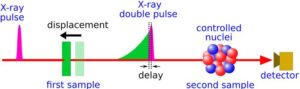

In the experiment, the researchers around project leader Jörg Evers (MPIK) used two samples enriched with the iron isotope ⁵⁷Fe, which are irradiated with short X-ray pulses from the synchrotron (Fig. 1). In the first sample, they generated a controllable double X-ray pulse, which was then used to control the dynamics of the nuclei in the second sample. The investigated nuclear excitations – which de-excite again by X-ray emission – are characterised by a very high sharpness in energy: so-called Mössbauer transitions. The discovery of the underlying effect (Nobel Prize 1961) was made by Rudolf Mössbauer in 1958 at the MPI for Medical Research, from which the MPIK spun off in the same year.

To generate the double pulse, the nuclei of the first sample are excited by the short X-ray pulse and, due to the high energy sharpness, release this excitation comparably slow in form of a second X-ray pulse. In the experiment, the sample is shifted quickly between the excitation and the de-excitation by a small distance corresponding to about half the X-ray wavelength. This changes the time of flight of the second pulse to the second sample, and thus shifts the position of the waves of the two X-ray pulses (relative phase) with respect to each other.

This double pulse now allows to control the nuclei in the second sample. The first pulse excites a quantum-mechanical dynamic in the nucleus, analogous to the oscillating swing. The second pulse changes this dynamic, depending on the relative phase of the two X-ray pulses. For example, if the wave of the second pulse hits the second sample in phase with the nuclear dynamics, the nuclei are further excited. By varying the relative phase, the researchers were able to switch between further excitation of the nuclei and de-excitation of the nuclei, and thus control the quantum-mechanical state of the nuclei. This can be reconstructed from the measured interference structures of the X-ray radiation behind the second sample (Fig. 2).

An acoustic analogy is illustrated in the attachment: Here, the Mössbauer nuclei of the samples correspond to tuning forks that are excited by a short bang (“starting shot”, analogous to the synchrotron pulse) and in turn sound slightly damped with their precisely defined frequency. The sound of the first fork thus hits the second fork after the bang as an additional excitation. In case (a), this sound wave moves opposite to the second fork, so that its oscillation is de-excited. In case (b), the first fork is quickly shifted so that its sound matches the movement of the second fork instead and thus excites it more.

Given the extreme demands required to control atomic nuclei (the displacement of the first sample by half a wavelength is of the order of an atomic radius), the apparently small influence of external disturbances on the quality of the experiment is surprising. Nevertheless, this works – due to the short duration of a measurement sequence, during which the main disturbing movements are virtually frozen. This stability is a prerequisite for future new applications based on nuclear transitions: more precise time standards, investigation of the variation of fundamental constants or the search for new physics beyond the accepted models.

In the field of atomic dynamics, far-reaching control is the key to many applications. The possibilities demonstrated here open the door to new experimental approaches based on the control of nuclear dynamics, e.g. by preparing nuclei in particular quantum states allowing for more precise measurements. Insofar as future X-ray sources would enable stronger excitation of the nuclei, nuclear batteries that can store and release large amounts of energy in internal excitations of the nuclei without nuclear fission or fusion would also be conceivable.

Wissenschaftliche Ansprechpartner:

apl. Prof. Dr. Jörg Evers

Leading scientist

Max-Planck-Institut für Kernphysik, Heidelberg

Phone: +49 6221 516-177

Email: joerg.evers@mpi-hd.mpg.de

Dr. Christian Ott

Leading scientist

Max-Planck-Institut für Kernphysik, Heidelberg

Tel.: +49 6221 516-577

Email: christian.ott@mpi-hd.mpg.de

Prof. Dr. Thomas Pfeifer

Director

Max-Planck-Institut für Kernphysik, Heidelberg

Phone: +49 6221 516-380

Email: thomas.pfeifer@mpi-hd.mpg.de

Honorarprof. Dr. Christoph H. Keitel

Director

Max-Planck-Institut für Kernphysik, Heidelberg

Phone: +49 6221 516-150

Email: keitel@mpi-hd.mpg.de

Originalpublikation:

Coherent X-ray-optical control of nuclear excitons

K. P. Heeg, A. Kaldun, C. Strohm, C. Ott, R. Subramanian, D. Lentrodt, J. Haber, H.-C. Wille, S. Goerttler, R. Rüffer, C. H. Keitel, R. Röhlsberger, T. Pfeifer and J. Evers

Nature, 17. Februar 2021, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03276-x

Weitere Informationen:

http://www.mpi-hd.mpg.de/mpi/en/forschung/abteilungen-und-gruppen/theoretische-q… Group of Jörg Evers at MPIK

http://www.mpi-hd.mpg.de/mpi/en/research/scientific-divisions-and-groups/quantum… Group of Christian Ott et MPIK

http://www.esrf.eu European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF)

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

NASA: Mystery of life’s handedness deepens

The mystery of why life uses molecules with specific orientations has deepened with a NASA-funded discovery that RNA — a key molecule thought to have potentially held the instructions for…

What are the effects of historic lithium mining on water quality?

Study reveals low levels of common contaminants but high levels of other elements in waters associated with an abandoned lithium mine. Lithium ore and mining waste from a historic lithium…

Quantum-inspired design boosts efficiency of heat-to-electricity conversion

Rice engineers take unconventional route to improving thermophotovoltaic systems. Researchers at Rice University have found a new way to improve a key element of thermophotovoltaic (TPV) systems, which convert heat…