Researchers discover direct link between agricultural runoff and massive algal blooms in the sea

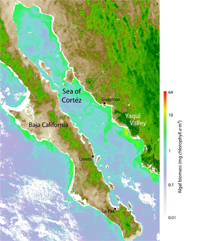

A NASA satellite image of a large algal bloom in the Sea of Cortez

Scientists have found the first direct evidence linking large-scale coastal farming to massive blooms of marine algae that are potentially harmful to ocean life and fisheries.

Researchers from Stanford University’s School of Earth Sciences made the discovery by analyzing satellite images of Mexico’s Sea of Cortez, also known as the Gulf of California-a narrow, 700-mile-long stretch of the Pacific Ocean that separates the Mexican mainland from the Baja California Peninsula. Immortalized in the 1941 book Sea of Cortez, by writer John Steinbeck and marine biologist Edward Ricketts, the region remains a hotspot of marine biodiversity and one of Mexico’s most important commercial fishing centers.

The results of the Stanford study will be presented at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in San Francisco on Dec. 13.

Algal blooms

Algal blooms occur naturally when cold-water upwellings bring from the seafloor to the surface nutrients that stimulate the rapid reproduction and growth of microscopic algae, also known as phytoplankton. These events often benefit marine ecosystems by generating tons of algae that are consumed by larger organisms.

But several phytoplankton species produce harmful blooms, known as red or brown tides, which release toxins in the water that can poison mollusks and fish. Excessively large blooms can also overwhelm a marine ecosystem by creating oxygen-depleted “dead zones” in the ocean. Scientists have long suspected that many harmful blooms are fueled by fertilizer runoff from farming operations, which in many regions pour tons of excess nitrogen and other nutrients into rivers that eventually flow into coastal waters. However, some agricultural industry groups contend that there is not enough evidence to link farm runoff to red tides or dead zones.

Satellite imagery

To assess the impact of agriculture on marine algae, Stanford scientists turned their attention to one of Mexico’s most productive coastal farming regions-the Yaqui River Valley, which drains into the Sea of Cortez.

“The Yaqui Valley agricultural area is 556,000 acres [225,000 hectares] of irrigated wheat,” said Pamela A. Matson, the dean of Stanford’s School of Earth Sciences and co-author of the AGU study. “The entire valley is irrigated and fertilized in very short windows of time during a six-month cycle. The excess water from irrigation runs off through streams and channels into the estuaries, and then out to sea.”

Matson and her colleagues wondered if each fertilization and irrigation event would trigger a noticeable phytoplankton bloom near the mouth of the Yaqui River, which is located on the mainland side of the Sea of Cortez. To find out, the researchers analyzed a series of images from an orbiting NASA satellite called SeaWiFS, which is equipped with special light-sensitive instruments that can detect phytoplankton floating near the surface of the sea. “These instruments measure the level of greenness in the water,” explained Kevin R. Arrigo, an associate professor of geophysics at Stanford and co-author of the AGU paper. “The greener the water, the more phytoplankton there are.”

Dramatic results

Stanford doctoral candidate Mike Beman carefully analyzed dozens of SeaWiFS images taken over the Sea of Cortez from 1998 through 2002. The results were dramatic. “I looked at five years of satellite data,” said Beman, lead author of the study. “There were roughly four irrigation events per year, and right after each one, you’d see a bloom appear within a matter of days.”

Each bloom was enormous, he said, covering from 19 to 223 square miles (50 to 577 square kilometers) of the Sea of Cortez and lasting several days. “Sometimes eddies actually pulled the plumes across the gulf, from the mainland side all the way to the Baja Peninsula,” Beman added. “Mike found that immediately following each one-week window in which much of the valley was irrigated, there was a response in the ocean off the coast of the Yaqui Valley,” Matson explained.

“We were quite surprised,” Arrigo added, noting that the AGU paper marks the first time that scientists have documented a “one-to-one correspondence between an irrigation event and a massive algal bloom.”

Red tides and dead zones

According to the researchers, artificially induced algal blooms could have major impacts on recreational and commercial fishing, major industries in the Sea of Cortez. Red tides, for example, can cause outbreaks of life-threatening diseases, such as paralytic shellfish poisoning, which can shut down mussel and clam harvesting for long periods of time.

Another concern is hypoxia, or oxygen depletion, which is caused by excessive algae growth. As the algal mass sinks, it is consumed by bacteria, which use up most of the oxygen in the water as they multiply. The result is an oxygen-depleted dead zone at the bottom of the sea where few creatures can survive. A massive dead zone appears every summer in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Louisiana and Texas. Scientists believe that agricultural runoff from the Mississippi River plays a pivotal role in creating this annual dead zone, which measured 8,500 square miles (22,000 square kilometers) in 2002-an area bigger than the state of Massachusetts.

“In the Sea of Cortez, there’s the possibility that hypoxia could occur at a local scale, which could be devastating to the shrimp and shellfish industries,” Matson said. “Shrimp fisheries are very important economically, and they’re already under a lot of stress from overfishing and aquaculture. It is possible that agricultural runoff could cause additional stress if it does lead to toxic blooms or hypoxia.” She and her colleagues plan to conduct follow-up studies to assess the ecological impact of Yaqui Valley runoff events.

“The availability of high-resolution satellite data has opened up a whole new opportunity to look at the importance of what’s going on on land in the sea,” Matson added. “This study shows that you have to pay attention to the land-sea connections.”

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.stanford.eduAll latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Parallel Paths: Understanding Malaria Resistance in Chimpanzees and Humans

The closest relatives of humans adapt genetically to habitats and infections Survival of the Fittest: Genetic Adaptations Uncovered in Chimpanzees Görlitz, 10.01.2025. Chimpanzees have genetic adaptations that help them survive…

You are What You Eat—Stanford Study Links Fiber to Anti-Cancer Gene Modulation

The Fiber Gap: A Growing Concern in American Diets Fiber is well known to be an important part of a healthy diet, yet less than 10% of Americans eat the minimum recommended…

Trust Your Gut—RNA-Protein Discovery for Better Immunity

HIRI researchers uncover control mechanisms of polysaccharide utilization in Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Researchers at the Helmholtz Institute for RNA-based Infection Research (HIRI) and the Julius-Maximilians-Universität (JMU) in Würzburg have identified a…