UC Riverside entomologists report bee-dancing brings more food to honeybee colonies

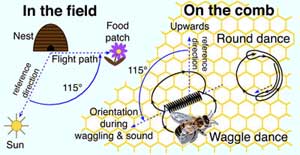

Diagram of the honeybee dance. (Credit: P. Kirk Visscher.) <br>

Honeybees communicate by dancing. The dances tell worker bees where to find nectar. A UC Riverside study reports that under natural foraging conditions the communication of distance and direction in the dance language can increase the food collection of honeybee colonies. The study also confirms that bees use this directional information in locating the food sources advertised in the dance.

Based on work done in 2001 in the Agricultural Experiment Station at UC Riverside, P. Kirk Visscher, professor of entomology, and Gavin Sherman, former graduate student in the department of entomology, report their findings in a paper entitled “Honeybee colonies achieve fitness through dancing” in the journal Nature.

The honey bee “dance language,” first described in the 1940s, reflects the distance and direction to the food source visited by the forager. A bee returning from a rich source of food will “dance” on the vertical comb surface by running in a circle. On each revolution, the bee will bisect the circle at an angle. The angle with respect to 12 o’clock represents the angle to fly with respect to the sun. If the bee ran from 6 to 12 o’clock (i.e., straight up), this would communicate to the other bees to fly directly towards the sun. As the bee dances, it also waggles its abdomen whilst crossing the circle. The number of waggles tells the other bees how far away from the beehive the nectar is. The more the waggles, the greater the distance to the nectar.

“The dance language is the most complex example of symbolic communication in any animal other than primates,” said Visscher. “Our study is the first test of the adaptive value of the dance language. It provides insights that may be of use in manipulating foraging behavior of honeybees for pollination of crops.”

There has been a long-simmering controversy over whether the direction and distance information in the dance is actually decoded by the recruits which follow the dances, or whether recruitment is based on the recruits learning only the odor food source from the dancer, and subsequently searching out the food based on odor alone. Several experiments have been published that have convinced most scientists that the bees can decode the direction and distance information, but the relative role of odor and location information has remained in question.

To test the effect of the information in the dance, Sherman and Visscher turned the normally vertical beehive on its side. With the combs horizontal, there was no upward reference for the dancer to use in orienting her waggle runs, and it performed disoriented dances, in which the waggle runs pointed in all directions. To experimentally restore dance information, the experimenters provided a directional light source, which the bees interpreted as the sun. The bees proceeded to do well-oriented dances at the angle relative to the light.

Using these treatments, Sherman and Visscher compared the weight gained by colonies which had oriented dances with that gained by colonies with disoriented dances. To control for colony-to-colony differences, the researchers exchanged treatments periodically. Overall, colonies with oriented dances collected more food, they found. However, this effect was strong only during the winter season. During the summer there was a weak difference, during autumn no difference in food collection. “In the ecology of honeybee colony, though, even short periods of intense food collection can make the difference between survival and death by starvation,” Visscher said.

The UC Riverside study also addresses the issues of the dance language controversy. Bees were recruited to syrup feeders in greater numbers when they followed dances which contained distance and direction information as well as odor than when they followed disoriented dances which could only communicate odor. However, at feeders 250 meters from the colony, about one quarter of the recruits did arrive with only odor information. As the distance increased, though, the bees from hives with oriented dances comprised an increasing proportion of the recruits.

Bees have been producing honey as they do today for at least 150 million years. They produce honey as food stores for the hive during the long months of winter when flowers are not in bloom and when, therefore, little or no nectar is available to them. The honeybee has three pairs of legs, four wings, a stinger and a special stomach that holds nectar. It is the only insect that produces food eaten by humans.

The University of California’s entomological research in Southern California dates back to 1906. Over the years, the UC Riverside Department of Entomology has excelled in virtually all phases of entomological research and developed a scope of expertise unmatched by any other entomology department in the country. Today, the UC Riverside campus is on the cutting edge of advanced entomological research and features a unique new Insectary and Quarantine facility that permits the safe study of exotic organisms from around the world.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Agricultural and Forestry Science

Newest articles

First-of-its-kind study uses remote sensing to monitor plastic debris in rivers and lakes

Remote sensing creates a cost-effective solution to monitoring plastic pollution. A first-of-its-kind study from researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities shows how remote sensing can help monitor and…

Laser-based artificial neuron mimics nerve cell functions at lightning speed

With a processing speed a billion times faster than nature, chip-based laser neuron could help advance AI tasks such as pattern recognition and sequence prediction. Researchers have developed a laser-based…

Optimising the processing of plastic waste

Just one look in the yellow bin reveals a colourful jumble of different types of plastic. However, the purer and more uniform plastic waste is, the easier it is to…