How long do firms live? Research finds patterns of company mortality in market data

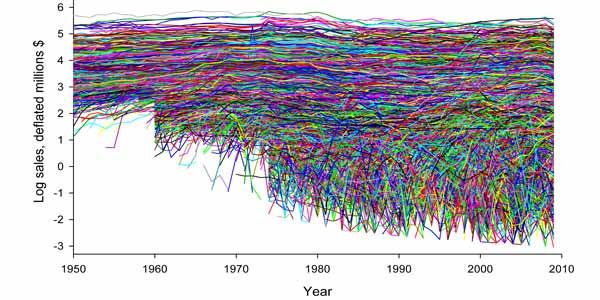

Sizes of some 30,000 companies traded publicly on US markets from 1950-2009, measured by their sales (controlling for inflation and GDP growth). The relatively rapid growth of smaller companies near the beginnings of their lifespans account for the ragged lower portion of the chart, as well as the relatively steep initial sales increases. As companies reach maturity, their sales tend to level off. Credit: Marcus Hamilton and Madeleine Daepp

Companies come and go for a variety of reasons. Some are bought, some merge with others, and some go out of business completely. There's no shortage of theories about why.

“The theory of the firm–there are whole books on what people think is going on,” says Marcus Hamilton, an SFI postdoctoral fellow and corresponding author of a new paper published in the journal Royal Society Interface.

Despite that, he says, “there is remarkably little quantitative work” on what economists call company mortality, and existing theory and evidence yield contradictory answers. Some researchers think younger companies are more likely to die than older ones, while others think just the opposite.

“We wanted to see if there was any kind of standard behavior or if it was just random,” Hamilton says.

Hamilton, SFI Distinguished Professor Geoffrey West, and SFI Professor Luis Bettencourt asked Madeleine Daepp, then an Edward A. Knapp Undergraduate Fellow at SFI and first author of the new paper, to take the lead. “We gave her this basic idea, and she did the heavy lifting,” Hamilton says. Daepp is now a graduate student at the University of British Columbia.

The heavy lifting, Hamilton explains, was going through Standard and Poor's Compustat, an expansive database of information on publicly-traded companies dating back to 1950. Using a statistical technique called survival analysis, Daepp and her mentors discovered something no one had predicted: a firm's mortality rate — its risk of dying in, say, the next year — had nothing to do with how long it had already been in business or what kinds of products it produced.

“It doesn't matter if you're selling bananas, airplanes, or whatever,” Hamilton says — the mortality rate is the same. Though the number, of course, varies from firm to firm, the team estimated that the typical company lasts about ten years before it's bought out, merges, or gets liquidated.

“The next question is, why might that be?” Hamilton says. The new paper largely avoids engaging with any particular economic model, though the researchers have some hypotheses inspired by ecological systems, where plants and animals have their own internal dynamics but must also compete for scarce resources — just like businesses do.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Business and Finance

This area provides up-to-date and interesting developments from the world of business, economics and finance.

A wealth of information is available on topics ranging from stock markets, consumer climate, labor market policies, bond markets, foreign trade and interest rate trends to stock exchange news and economic forecasts.

Newest articles

First-of-its-kind study uses remote sensing to monitor plastic debris in rivers and lakes

Remote sensing creates a cost-effective solution to monitoring plastic pollution. A first-of-its-kind study from researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities shows how remote sensing can help monitor and…

Laser-based artificial neuron mimics nerve cell functions at lightning speed

With a processing speed a billion times faster than nature, chip-based laser neuron could help advance AI tasks such as pattern recognition and sequence prediction. Researchers have developed a laser-based…

Optimising the processing of plastic waste

Just one look in the yellow bin reveals a colourful jumble of different types of plastic. However, the purer and more uniform plastic waste is, the easier it is to…