New source of methane discovered in the Arctic Ocean

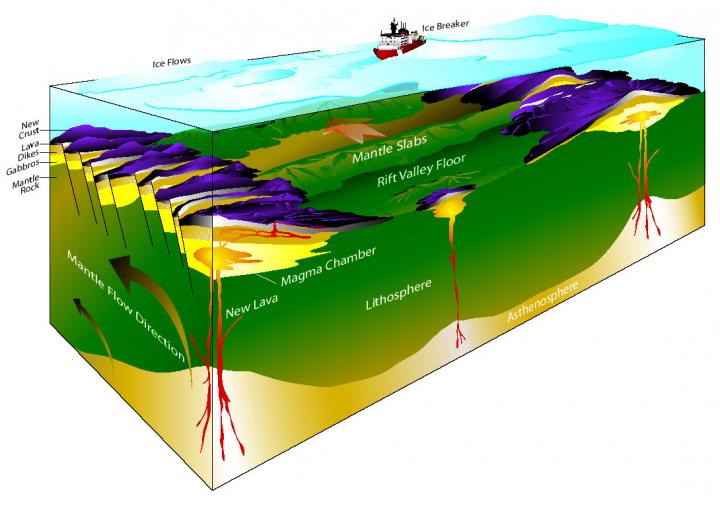

Ultra-slow spreading ocean ridges were discovered in the Arctic in 2003 by scientists at Woods Hole Ocenographic Institution. They found that for large regions the sea floor splits apart by pulling up solid rock from deep within the earth. These rocks, known as peridotites (after the gemstone peridot) come from the deep layer of the earth known as the mantle. Credit: Dr. Henry J.B. Dick, WHOI / nsf.gov.

But there is another type of methane that can appear under specific circumstances: Abiotic methane is formed by chemical reactions in the oceanic crust beneath the seafloor.

New findings show that deep water gas hydrates, icy substances in the sediments that trap huge amounts of the methane, can be a reservoir for abiotic methane.

One such reservoir was recently discovered on the ultraslow spreading Knipovich ridge, in the deep Fram Strait of the Arctic Ocean. The study suggests that abiotic methane could supply vast systems of methane hydrate throughout the Arctic.

The study was conducted by scientists at Centre for Arctic Gas Hydrate, Environment and Climate (CAGE) at UiT The Arctic Univeristy of Norway. The results were recently published in Geology online and will be featured in the journal's May issue.

Previously undescribed

“Current geophysical data from the flank of this ultraslow spreading ridge shows that the Arctic environment is ideal for this type of methane production. ” says Joel Johnson associate professor at the University of New Hampshire (USA), lead author, and visiting scholar at CAGE.

This is a previously undescribed process of hydrate formation; most of the known methane hydrates in the world are fueled by methane from the decomposition of organic matter.

“It is estimated that up to 15 000 gigatonnes of carbon may be stored in the form of hydrates in the ocean floor, but this estimate is not accounting for abiotic methane. So there is probably much more.” says co-author and CAGE director Jürgen Mienert.

Life on Mars?

NASA has recently discovered traces of methane on the surface of Mars, which led to speculations that there once was life on our neighboring planet. But an abiotic origin cannot be ruled out yet.

On Earth it forms through a process called serpentinization.

“Serpentinization occurs when seawater reacts with hot mantle rocks exhumed along large faults within the seafloor. These only form in slow to ultraslow spreading seafloor crust. The optimal temperature range for serpentinization of ocean crust is 200 – 350 degrees Celsius.” says Johnson.

Methane produced by serpentinization can escape through cracks and faults, and end up at the ocean floor. But in the Knipovich Ridge it is trapped as gas hydrate in the sediments. How is it possible that relatively warm gas becomes this icy substance?

“In other known settings the abiotic methane escapes into the ocean, where it potentially influences ocean chemistry. But if the pressure is high enough, and the subseafloor temperature is cold enough, the gas gets trapped in a hydrate structure below the sea floor. This is the case at Knipovich Ridge, where sediments cap the ocean crust at water depths up to 2000 meters. ” says Johnson.

Stable for two million years

Another peculiarity about this ridge is that because it is so slowly spreading, it is covered in sediments deposited by fast moving ocean currents of the Fram Strait. The sediments contain the hydrate reservoir, and have been doing so for about 2 million years.

” This is a relatively young ocean ridge, close to the continental margin. It is covered with sediments that were deposited in a geologically speaking short time period -during the last two to three million years. These sediments help keep the methane trapped in the sea floor.” says Stefan Bünz of CAGE, also a co-author on the paper.

Bünz says that there are many places in the Arctic Ocean with a similar tectonic setting as the Knipovich ridge, suggesting that similar gas hydrate systems may be trapping this type of methane along the more than 1000 km long Gakkel Ridge of the central Arctic Ocean.

The Geology paper states that such active tectonic environments may not only provide an additional source of methane for gas hydrate, but serve as a newly identified and stable tectonic setting for the long-term storage of methane carbon in deep-marine sediments.

Need to drill

The reservoir was identified using CAGE's high resolution 3D seismic technology aboard research ressel Helmer Hanssen. Now the authors of the paper wish to sample the hydrates 140 meters below the ocean floor, and decipher their gas composition.

Knipovich Ridge is the most promising location on the planet where such samples can be taken, and one of the two locations where sampling of gas hydrates from abiotic methane is possible.

” We think that the processes that created this abiotic methane have been very active in the past. It is however not a very active site for methane release today. But hydrates under the sediment, enable us to take a closer look at the creation of abiotic methane through the gas composition of previously formed hydrate.” says Jürgen Mienert who is exploring possibilities for a drilling campaign along ultra-slow spreading Arctic ridges in the future.

Media Contact

Jürgen Mienert

jurgen.mienert@uit.no

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.nsf.govAll latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Innovative vortex beam technology

…unleashes ultra-secure, high-capacity data transmission. Scientists have developed a breakthrough optical technology that could dramatically enhance the capacity and security of data transmission (Fig. 1). By utilizing a new type…

Tiny dancers: Scientists synchronise bacterial motion

Researchers at TU Delft have discovered that E. coli bacteria can synchronise their movements, creating order in seemingly random biological systems. By trapping individual bacteria in micro-engineered circular cavities and…

Primary investigation on ram-rotor detonation engine

Detonation is a supersonic combustion wave, characterized by a shock wave driven by the energy release from closely coupled chemical reactions. It is a typical form of pressure gain combustion,…