New Observations on Shape of Ocean Mountain Ranges Turn an Old Idea Upside Down

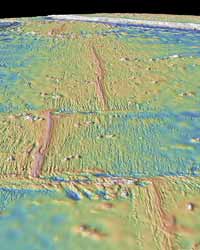

Figure 1. Perspective view from the south of the mid-ocean ridge off the coast of Central America (far distance) showing how the morphology of this spreading ridge changes across transform faults and smaller ridge offsets. Note how the more westerly segments (offset in the direction of ridge migration) are shallower and broader than their neighbors. Image credit: Bill Haxby

New findings suggest that surface geometry determines volcanic activity

What causes the peaks and valleys of the world’s great mountains? For continental ranges like the Appalachians or the Northwest’s Cascades, the geological picture is clearer. Continents crash or volcanoes erupt, then glaciers erode away. Yet scientists are still puzzling out what makes the highs high and the lows low for the planet’s largest mountain chain, the 55,000-mile-long Mid-Ocean Ridge.

This week in the journal Nature, scientists at Columbia University’s Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory describe new findings that challenge current thinking about how the silhouette of the mile’s high deepwater ridge is formed.

The long string of mountains that zig-zags across the ocean floor define the boundaries of the crustal plates that make up the Earth’s surface. At the center of the Mid-Ocean Ridge is a continuous fissure in which hot magma bubbles up from below and cools to become new crust material added to the plates on either side. For decades, the most popular explanation for the ridge’s distinct undulating topography has been that magma flows upward from the mantle interior in directed streams of differing sizes. Larger magma flows lead to higher, broader peaks, while a magma trickle or drought is reflected in lower, more narrow valleys.

But after analyzing thousands of miles of the Mid-Ocean Ridge, Lamont marine geologist Suzanne Carbotte and co-authors Christopher Small and Katie Donnelly disagree. They discovered that the height and width of underwater mountains are highly correlated to the direction that the ridge and connecting plates move across the surface of the planet.

“Our observations indicate that these variations in ridge height reflect a top down rather than a bottom up process,” said Carbotte. “The motion of the plates seems to be the important factor, not the mantle.”

The twelve crustal plates that make up the surface of the Earth are constantly jostling each other as some grow in size and others shrink. In response, the Mid-Ocean Ridge migrates very slowly, moving at a rate of about an inch a decade in relation to fixed hot areas of the mantle below. Each underwater range in the mountain chain can be offset from the next by up to hundreds of miles, connected by a long perpendicular fault line. This geometry creates distinct ridge segments jutting back and forth.

Their results have implications for geologists concerned with crust and mantle structure, as well as for biologists interested in life around hydrothermal vents. Previously, many scientists believed that the structure of the upper mantle must be both physically and chemically diverse in order to explain the peaks and valleys along the Mid-Ocean Ridge. This implied that ridge segment would spend time above both high and low magma streams as it travels over the mantle.

“Our findings suggest that the upper mantle could be quite uniform and still produce a varied topography due solely to plate migration,” said Carbotte. “This has all sorts of implications. For example, if certain ridge segments are just more volcanically active than others due simply to their geometry, those locations may host hydrothermal communities over very long periods of time.”

This study was funded by The National Science Foundation.

The Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, a member of The Earth Institute at Columbia University, is one of the world’s leading research centers examining the planet from its core to its atmosphere, across every continent and every ocean. From global climate change to earthquakes, volcanoes, environmental hazards and beyond, Observatory scientists provide the basic knowledge of Earth systems needed to inform the future health and habitability of our planet. For more information, visit www.ldeo.columbia.edu.

The Earth Institute at Columbia University is among the world’s leading academic centers for the integrated study of Earth, its environment, and society. The Earth Institute builds upon excellence in the core disciplines—earth sciences, biological sciences, engineering sciences, social sciences and health sciences—and stresses cross-disciplinary approaches to complex problems. Through its research training and global partnerships, it mobilizes science and technology to advance sustainable development, while placing special emphasis on the needs of the world’s poor.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.earth.columbia.eduAll latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Parallel Paths: Understanding Malaria Resistance in Chimpanzees and Humans

The closest relatives of humans adapt genetically to habitats and infections Survival of the Fittest: Genetic Adaptations Uncovered in Chimpanzees Görlitz, 10.01.2025. Chimpanzees have genetic adaptations that help them survive…

You are What You Eat—Stanford Study Links Fiber to Anti-Cancer Gene Modulation

The Fiber Gap: A Growing Concern in American Diets Fiber is well known to be an important part of a healthy diet, yet less than 10% of Americans eat the minimum recommended…

Trust Your Gut—RNA-Protein Discovery for Better Immunity

HIRI researchers uncover control mechanisms of polysaccharide utilization in Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Researchers at the Helmholtz Institute for RNA-based Infection Research (HIRI) and the Julius-Maximilians-Universität (JMU) in Würzburg have identified a…