Sumatra earthquake three times larger than originally thought

Northwestern University seismologists have determined that the Dec. 26 Sumatra earthquake that set off a deadly tsunami throughout the Indian Ocean was three times larger than originally thought, making it the second largest earthquake ever instrumentally recorded and explaining why the tsunami was so destructive.

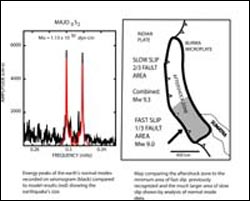

By analyzing seismograms from the earthquake, Seth Stein and Emile Okal, both professors of geological sciences in Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, calculated that the earthquake’s magnitude measured 9.3, not 9.0, and thus was three times larger. These results have implications for why Sri Lanka suffered such a great impact and also indicate that the chances of similar large tsumanis occurring in the same area are reduced.

“The rupture zone was much larger than previously thought,” said Stein. “The initial calculations that it was a 9.0 earthquake did not take into account what we call slow slip, where the fault, delineated by aftershocks, shifted more slowly. The additional energy released by slow slip along the 1,200-kilometer long fault played a key role in generating the devastating tsunami.”

The large tsunami amplitudes that occurred in Sri Lanka and India, said tsunami expert Okal, result from rupture on the northern, north-trending segment of the fault — the area of slow slip — because tsunami amplitudes are largest perpendicular to the fault.

Because the entire rupture zone slipped (both fast and slow slip fault areas), strain accumulated from subduction of the Indian plate beneath the Burma microplate has been released, leaving no immediate danger of a comparable ocean-wide tsunami being generated on this segment of the plate boundary. However, the danger of a local tsunami due to a powerful aftershock or a large tsunami resulting from a great earthquake on segments to the south remains.

The analysis technique used by Stein and Okal to extract these data from the earth’s longest period vibrations (normal modes) relied on results developed by them and colleague Robert Geller (now at the University of Tokyo) in their graduate studies almost 30 years ago. However, because such gigantic earthquakes are rare, these methods had been essentially unused until records of the Sumatra earthquake on modern seismometers became available.

The largest earthquake ever recorded, which measured 9.5, was in Chile on May 22, 1960.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.northwestern.eduAll latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Retinoblastoma: Eye-Catching Investigation into Retinal Tumor Cells

A research team from the Medical Faculty of the University of Duisburg-Essen and the University Hospital Essen has developed a new cell culture model that can be used to better…

A Job Well Done: How Hiroshima’s Groundwater Strategy Helped Manage Floods

Groundwater and multilevel cooperation in recovery efforts mitigated water crisis after flooding. Converting Disasters into Opportunities Society is often vulnerable to disasters, but how humans manage during and after can…

Shaping the Future: DNA Nanorobots That Can Modify Synthetic Cells

Scientists at the University of Stuttgart have succeeded in controlling the structure and function of biological membranes with the help of “DNA origami”. The system they developed may facilitate the…