Purdue scientists unravel Midwest tornado formation

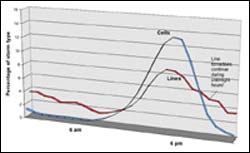

While people generally expect tornadoes to form from isolated storm cells in the evening in springtime, a survey of weather data led by Purdue researcher Robert "Jeff" Trapp has revealed that a significant number of tornadoes form under unexpected circumstances. Especially in the Midwest, many tornadoes form from "line-shaped" storms often associated with large weather fronts. Such tornadoes are more likely to form during winter months, late at night. These data were taken from a survey of 3,800 tornadoes that formed over the United States from 1998-2000. (Purdue University/Trapp laboratories)

Purdue University study of tornado formation indicates that twisters can develop in unexpected ways and at unexpected times and places, a discovery that presents a new twist to weather watchers across the country.

Although tornadoes are often conceived of as arising from springtime storms that develop in early evenings out of isolated weather cells, a new study spearheaded by Purdue’s Robert “Jeff” Trapp indicates those conceptions often fail to hold, especially in the Midwest. Although far from the so-called “Tornado Alley,” a region that falls generally in the plains of Texas, Oklahoma and Kansas, the Midwest still experiences a high number of the storms every year.

After examining data on more than 3,800 U.S. tornadoes, Trapp’s team has found that many twisters develop within the line-shaped storm fronts that often sweep across the country. The twist is that these are tornadoes that are more likely to form late at night and in colder months.

“The upshot of our analysis is that tornadoes form under a broader set of circumstances than meteorologists once thought, and this is especially true if you live far from Tornado Alley,” said Trapp, an associate professor of earth and atmospheric sciences in Purdue’s College of Science. “If you’re driving in the rain on an October midnight near Lake Michigan, remember that a tornado is not outside the realm of possibility.”

Trapp’s study, which he performed with colleagues at the University of Oklahoma, Colorado State University and the National Severe Storms Laboratory, appears in the February issue of the journal Weather and Forecasting. As a first step toward improving our ability to predict tornado strikes, which often come with only a few minutes’ warning, the group initially set out to find what types of storms generally produce the destructive funnels.

“In the heart of Tornado Alley, tornadoes most often develop from relatively small ’cell’ storms that look like blotches on a Doppler radar weather map,” Trapp said. “Over time, these cells frequently merge into line-shaped storms that can stretch hundreds of miles. The conventional wisdom has been that line storms don’t often spawn tornadoes, but we found that a significant number did.”

The group analyzed 3,828 tornadoes that were spotted in the United States from 1998 to 2000. Though 79 percent of these tornadoes came from cells, Trapp said, 18 percent came from line storms nationwide. But in the Midwest, those numbers varied widely. In Indiana, for example, about half of the tornadoes that developed came from line storms.

“This implies that we may be overlooking many tornado-breeding storms in the Midwest and elsewhere,” Trapp said. “Complicating the issue is that what we know about tornado formation is based largely on the cell-type storms observed in Oklahoma and Texas.”

Cell storms often form in springtime in the late afternoon, which is why most storm warnings in Tornado Alley are issued in the evening, Trapp said. But line storms often form later at night and also in the cool season, between October and March.

“These are the hours and months when people probably least expect severe weather,” Trapp said. “In fact, they may not even see a tornado coming because of the lateness of the hour.”

The silver lining to all these clouds is that tornadoes are less frequent overall in the Midwest – Indiana only experiences about 20 tornadoes a year, compared to about 52 in Oklahoma and 124 in Texas – and Midwest storms are often weaker than those of the Plains. But because many of these tornadoes may go undetected, Trapp said, people outside Tornado Alley should begin to shift their thinking.

“We’re not trying to be alarmist with these findings,” he said. “But we hope that people will stay alert to tornado risk even outside the traditional severe storm season.”

Trapp said that the current study represents a step toward better weather prediction, but there’s still much work to be done on the problem.

“This paper is meant to be the first in a series of studies of tornado development,” Trapp said. “Now that we have a better picture of when and where they form, we can begin to develop tools that can serve a practical purpose. For now, we are merely trying to raise awareness among weather watchers about tornado-forming situations that, until now, have been, figuratively speaking, beneath our radar.”

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.purdue.eduAll latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Humans vs Machines—Who’s Better at Recognizing Speech?

Are humans or machines better at recognizing speech? A new study shows that in noisy conditions, current automatic speech recognition (ASR) systems achieve remarkable accuracy and sometimes even surpass human…

Not Lost in Translation: AI Increases Sign Language Recognition Accuracy

Additional data can help differentiate subtle gestures, hand positions, facial expressions The Complexity of Sign Languages Sign languages have been developed by nations around the world to fit the local…

Breaking the Ice: Glacier Melting Alters Arctic Fjord Ecosystems

The regions of the Arctic are particularly vulnerable to climate change. However, there is a lack of comprehensive scientific information about the environmental changes there. Researchers from the Helmholtz Center…