Computer model offers new tool to probe woburn toxic waste site

A computer model developed at Ohio State University is giving researchers a new understanding of how municipal wells at a famous toxic waste site in Woburn, Massachusetts, came to be contaminated, and how much contamination was delivered to residents.

As dramatized in the book and movie A Civil Action, a cluster of childhood leukemia cases in Woburn led to a lengthy court battle in the 1980s, during which three commercial companies were accused of dumping toxic chemicals that entered two of the towns water supply wells.

The wells – known as G and H — operated from 1964 to 1979, when they were permanently shut down by the state of Massachusetts. In the trial, the jury found one company — manufacturer of industrial machines W.R. Grace and Co. — liable for the contamination.

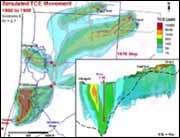

The Ohio State computer model, which simulates the movement of a plume of contamination as it spreads underground away from its source, is the most extensive of its kind ever used at Woburn. It also uses new information acquired after the 1985 trial, including data from two additional sources of contamination.

The results of the computer model cant absolutely explain how the Woburn wells became contaminated and cant be used to assign liability, but they do provide some plausible scenarios of what happened. The results suggest the chemicals from W.R. Grace probably never reached the wells and, if they did, they arrived near the time the wells were shut down.

The most plausible scenario is that much of the toxic chemicals in the wells came from the Beatrice Foods Corp. and Hemingway Trucking Co. properties, said E. Scott Bair, professor and chair of geological sciences at Ohio State. Most surprising though, a substantial amount of the groundwater pumped by the wells originated in the nearby Aberjona River, which is another likely source of chemical contamination.

The data collected by EPA at wells G and H indicate there were toxic chemicals in the soil and groundwater on at least five properties around Woburn, and probably in the nearby Aberjona River and wetland,” said Maura Metheny, an Ohio State graduate student in the Department of Geological Sciences who performed the work.

Metheny and Bair described the plume model, as well as its implications to the Woburn trial and public health concerns, in two back-to-back presentations at the Geological Society of America meeting in Seattle on November 5.

In the first presentation, Metheny related the models month-by-month, 26-year predictions of how plumes of two industrial solvents, trichloroethene (TCE) and perchlorothene (PCE), traveled in the groundwater system from the five contaminated properties to wells G and H.

After Methenys talk, Bair described how they made monthly estimates of how much TCE and PCE was delivered through the city’s water mains to residences and businesses in different parts of town.

In particular, Bair described how they linked results from the plume model to a water distribution model developed in 1990 by the late Peter Murphy, a former professor of engineering at the University of Massachusetts. Murphys model calculated the amount of water from wells G and H that was routed month-by-month to different parts of the city.

Linked together, the models form a powerful forensic tool, Bair said. With them, we can estimate a plausible range of TCE and PCE concentrations captured by wells G and H, determine how the contaminated water mixed with clean water from the six other city wells, and then estimate the amount of contaminants that were likely delivered to homes in Woburn,” Bair explained.

Bair said that this type of forensic research is part of an emerging field known as medical geology.

With the expertise of epidemiologists and statisticians, this type of house-by-house, month-by-month chemical exposure history could lead to insightful findings. It is information that did not exist during previous public health investigations of the childhood leukemias and other health problems in Woburn, he explained.

Among the great many physical and chemical factors Metheny took into account in her plume model were groundwater levels, variations in precipitation, changes in pumping rates of wells G and H, binding of TCE and PCE onto organic matter in the aquifer, and estimates of the dumped masses of contaminants.

In 2000, Metheny and Bair collected groundwater and dissolved gas samples from wells at the site, so Kip Solomon, a professor at the University of Utah, could calculate the age of the groundwater samples. Just as scientists use carbon dating to calculate the age of ancient organic material, geologists can measure the decay of tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, to gauge how long a sample of water has been in the ground.

Metheny then compared Solomons results to the groundwater ages computed using her plume model, and found that the two sets of ages closely matched.

The researchers also enlisted the help of Martin Van Oort, another of Bair’s graduate students, to construct a computer animation of a typical set of model results.

Metheny ran hundreds of simulations with the plume model to address uncertainties such as the release dates of TCE and PCE, and the concentration of the releases. She then compared the simulated concentrations of TCE and PCE to their measured concentrations in wells G and H and in monitoring wells across the site.

Each simulation took two to three days to run. I can see why nobody did this before — it took seven years of my life, Metheny said with a laugh.

The simulations were used to create a set of plausible scenarios of what may have happened in Woburn, each of which closely matched data measured at the sites.

For instance, in May 1979 — the month the wells were ordered closed — the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Quality Engineering measured TCE concentrations of 267 and 184 parts per billion (ppb) in wells G and H, respectively. One of the plausible scenarios computed by the model calculated values of 257 and 133 ppb. The public health standard for TCE is 5 ppb.

Metheny did the work to earn her masters and doctoral degrees at Ohio State. She is now a lecturer in the Department of Geology and Geography at Denison University in Granville, Ohio, while finishing her Ph.D. dissertation.

To Bair and Methenys knowledge, the linked models are unique.

The plume model also lends insight to the outcome of the Woburn trial, although that was not the scientists only intention.

We didnt set out to prove or disprove anyone’s trial testimony, Metheny explained. We just wanted to see if we could decipher how and when the chemicals got into the wells.

Our plume model is as good as it is because we approached it as unbiased scientists, she continued. We had the advantages of much faster computers loaded with memory and software that were not available to the litigants’ experts in the 1980s. We also had important data that had been collected after the trial ended, during all the Superfund cleanup work at the five contaminated properties, not just from the defendants’ properties.

“The overall purposes of the work are to help organizations such as EPA evaluate and cleanup the aquifer in Woburn and similar aquifers that are contaminated across the country, and to show public health professionals the types of chemical exposure histories that geologists can contribute to health studies,” explained Bair.

Although the jury found W.R. Grace and Co. liable for contaminating wells G and H, in some of the models plausible scenarios, the TCE plume emanating from W.R. Grace does not get to well G or well H.

“In the few plausible scenarios showing that contamination from the Grace property does reach wells G and H, the contamination arrived at the end of the period that the wells operated, and the concentration of TCE was low compared to what the wells captured from the other sources, Bair added.

The jury found another local company, Beatrice Foods Corp., not liable for contaminating wells G and H. But according to the model results, Bair and Metheny said most of the TCE entering the wells from the late 1960s through the 1970s probably came from the Beatrice property and the Hemingway Trucking Co. property, which are on the west side of the nearby Aberjona River. Lesser amounts of TCE captured by the wells probably came from the properties of UniFirst Corp., New England Plastics Corp., and W.R. Grace.

What surprised Metheny and Bair the most was the amount of water in the wells that originally came from the river, which further complicates the overall picture of contamination in the Woburn wells. From month to month, the wells typically produced water that varied from 20 percent river water content to 40 percent.

If the river water was contaminated with solvents, or the riverbed contained arsenic, chromium, and lead — as recent studies by EPA and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology indicate — then these contaminants also would have been captured by the wells, Bair said.

Metheny realizes her work does not present the absolute answer to what actually happened in Woburn.

The questions people really want answered, we will never be able to answer with complete certainty, she said.

No one can be 100 percent sure what happened, Bair agreed. We now have a range of realistic possibilities. Hopefully, our research provides epidemiologists and biostatisticians with information they can use in more robust statistical evaluations of the childhood leukemias and the other health effects in Woburn.”

Metheny and Bair acknowledge that their research holds emotional significance for many families in Woburn, in particular, those who lost a child or other loved one to leukemia. In an emotional evening in March of 2002, they presented their work to some of the plaintiff families and friends. The next day, they presented it to EPA and the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

All of Metheny and Bairs work was funded by Ohio State, including Bairs internal research funds as chair of the Department of Geological Sciences, and a grant he received from the university to create an undergraduate honors geology course based on A Civil Action.

To build his mock trial course, Bair called on Ohio State researchers from many different disciplines, including law and medicine. Students in the class learn about childhood leukemia and its treatment, groundwater flow, water chemistry, and contaminant plume movement. They then become expert witnesses in a mock trial —

training that will come in handy should they ever need to use their knowledge of geology in the courtroom, or in assessing a toxic waste site.

Congress established the Superfund program in 1980 to locate, investigate, and clean up the sites of chemical waste nationwide. The EPA administers the program, and in 1982 placed the Woburn wells G and H site on its National Priorities List as one of the most contaminated sites in the nation.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.geology.ohio-state.edu/courtroomAll latest news from the category: Ecology, The Environment and Conservation

This complex theme deals primarily with interactions between organisms and the environmental factors that impact them, but to a greater extent between individual inanimate environmental factors.

innovations-report offers informative reports and articles on topics such as climate protection, landscape conservation, ecological systems, wildlife and nature parks and ecosystem efficiency and balance.

Newest articles

Hyperspectral imaging lidar system achieves remote plastic identification

New technology could remotely identify various types of plastics, offering a valuable tool for future monitoring and analysis of oceanic plastic pollution. Researchers have developed a new hyperspectral Raman imaging…

SwRI awarded $26 million to develop NOAA magnetometers

SW-MAG data will help NOAA predict, mitigate the effects of space weather. NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recently awarded Southwest Research Institute a $26 million contract…

Protein that helps cancer cells dodge CAR T cell therapy

Discovery could lead to new treatments for blood cancer patients currently facing limited options. Scientists at City of Hope®, one of the largest and most advanced cancer research and treatment…