Advance in regenerative medicine

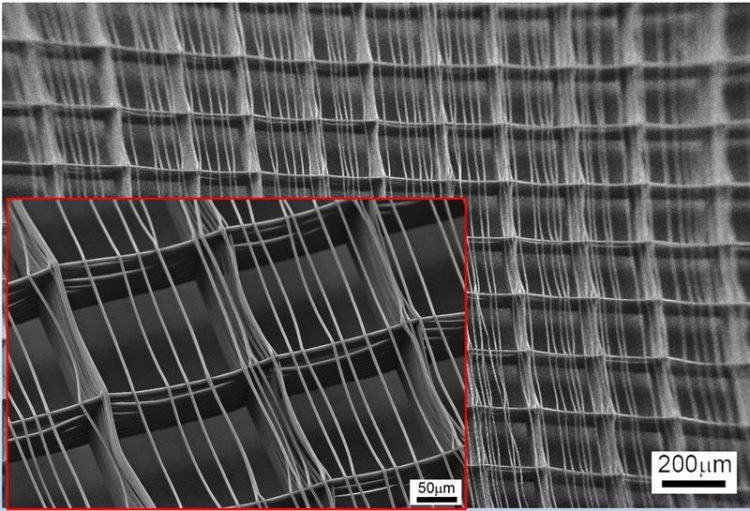

Polymers are spun to extremely fine threads which are then arranged to form fine meshes. This is the principle of Melt Electrospinning Writings. Photo: team Dalton

Paul Dalton is presently the only professor of biofabrication in Germany. About a year ago, the Australian researcher relocated to the Würzburg department for functional materials in medicine and dentistry.

By now, the 44-year-old professor has not only launched a “Biofabrication” master's programme, offered jointly by universities in the Netherlands, Australia and the University of Würzburg, but has also set up a laboratory that is unique in the world.

A pioneer of melt electrospinning writings

Dalton is the internationally leading pioneer in the field of so-called Melt Electrospinning Writings (MEW). “My primary research goal is to use this technique to create defined tissues,” the scientist says. MEW involves polymers being spun to extremely fine threads in an electric field which are then arranged to form fine meshes.

Dalton and his team have adopted this approach to produce novel tissues based on structures sized only a few nanometres to micrometres. In tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, these meshes serve as the scaffolding that allows the body's own cells to gradually build new tissue there.

Dalton's method has the major advantage of not needing any organic solvents unlike conventional electrostatic spinning methods. By processing polymers which are approved medical products, the structures created by MEW thus have the potential to arrive in clinics very quickly. “The primary goal is to regenerate soft tissue such as muscle, nerves and skin,” says Dalton.

Being built from the body's own cells, the implant is not rejected and thus no immunosuppressive drugs are needed. What is more, the body completely degrades all fibre structures after a defined period of time. Scientists today assume that in a few years this method will allow them to reconstruct breast tissue after breast cancer surgery.

Dalton has now realised a breakthrough improvement in these three-dimensional meshes in cooperation with scientists from Queensland University of Technology and universities in Utrecht and Oxford. The researchers present their results in the latest issue of Nature Communications.

Publication in Nature Communications

“We have successfully reinforced hydrogels with tissues developed by us to make the product nearly as stiff as naturally occurring articular cartilage while preserving its elasticity,” Dalton sums up the gist of their research. He considers this to be a major breakthrough since hydrogels, though easy to construct in their interaction with cells, generally have poor mechanical properties.

It is crucial in this context to imitate the natural environment as closely as possible, as cells in the natural tissue react to different types of mechanical stress such as pressure, tensile stress and shearing forces, which are instrumental to initiating the desired activity. The closer the artificial matrix resembles the natural one in terms of mechanical properties, the more likely the cells are to behave as desired, that is: to build a tissue-specific matrix and thereby repair and regenerate the damaged tissue. “And compression strength is crucial in particular for articular cartilage tissue, which acts as a natural shock absorber between the bones,” Dalton further.

A sound basis for the production of replacement tissue

The achievement of the international research team presented now could thus close a gap. Its material is much stiffer than tissues used so far, with the corresponding value being 50 times as high and preserved elasticity. “Our approach to reinforce hydrogels using three-dimensional printed microfibres is therefore a solid basis for producing replacement tissues that have the required properties,” Dalton emphasises.

Further tests have confirmed that the combination of hydrogels and the three-dimensional meshes made up of ultra-fine fibres developed by Dalton approximately reflects the conditions in the extracellular space in cartilage tissue. For this purpose, the scientists brought together chondrocytes, cartilage-producing cells, and the tissue in a bioreactor and observed how the cells behaved. The results were convincing: The cells operated exactly as they were expected to, which was determined by means of gene expression and matrix production. “This combination of a hydrogel and a microfibre network is therefore an appropriate environment for replacing cartilage tissue both from a mechanical and a biological point of view,” Dalton further.

Reinforcement of hydrogels using three-dimensionally printed microfibres. Jetze Visser, Ferry P.W. Melchels, June E. Jeon, Erik M. van Bussel, Laura S. Kimpton, Helen M. Byrne, Wouter J.A. Dhert, Paul D. Dalton, Dietmar W. Hutmacher & Jos Malda. Nature Communications, DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7933

The method used to produce the ultra-fine threads has been developed and constructed by the scientists themselves. The laboratory of the department for functional materials in medicine and dentistry is now equipped with devices of the fifth generation. What is special about them: They work without solvents and are controlled digitally. “This allows us to control the tissue design as desired. The resulting structures are extremely fine and flexible and can either be populated by cells or reject cells as required,” Dalton says. Moreover, the Würzburg MEW machines are highly reliable and the most advanced in the world. If necessary, they will run 24/7 in order to “produce new and fascinating products for medical applications,” as Dalton puts it.

Vita

Paul Dalton studied material sciences; already in his doctoral thesis at Lions Eye Institute in Perth, Australia, he worked on the development of an artificial cornea. He spent his postdoc time at the University of Toronto, Canada, and at the University of Aachen in Germany, where his research activities included hydrogels for nerve regeneration. As a research fellow at the University of Southampton (UK) he investigated to what extent hydrogel tissue causes inflammation in the spinal marrow. From 2009 to 2011, Dalton did research at Shanghai Jiao Tong University (China) and at Queensland University of Technology (Australia). Since May 2012, he has been professor of biofabrication at the department for functional materials in medicine and dentistry.

The “Biofabrication” master's programme

Next winter semester will see the launch of a new international master's programme that is about exactly this field of research: BIOFAB or fully “Biofabrication Training for Future Manufacturing”. This worldwide unique programme is jointly provided by:

• Queensland University of Technology (Australia)

• University of Wollongong (Australia)

• University Medical Center Utrecht (Netherlands)

• Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg (Germany)

The four participating universities will each accept ten students into the master's programme. The students will spend about half of their study time in Australia and Europe, respectively. At the end of the programme, the students will receive an international master's degree both in Australia and in Europe.

Contact

Prof. Dr. Paul Dalton, Phone: +49 0931 201-74081, paul.dalton@fmz.uni-wuerzburg.de

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.uni-wuerzburg.deAll latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

First-of-its-kind study uses remote sensing to monitor plastic debris in rivers and lakes

Remote sensing creates a cost-effective solution to monitoring plastic pollution. A first-of-its-kind study from researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities shows how remote sensing can help monitor and…

Laser-based artificial neuron mimics nerve cell functions at lightning speed

With a processing speed a billion times faster than nature, chip-based laser neuron could help advance AI tasks such as pattern recognition and sequence prediction. Researchers have developed a laser-based…

Optimising the processing of plastic waste

Just one look in the yellow bin reveals a colourful jumble of different types of plastic. However, the purer and more uniform plastic waste is, the easier it is to…