Lung images of twins with asthma add to understanding of the disease

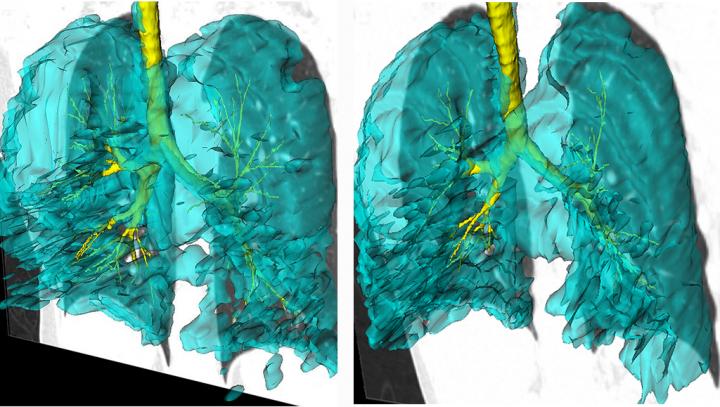

Researchers used a specialized MRI techniques to visualize the lungs of twins with asthma. While the twins are non-identical, the researchers found that they actually had identical ventilation defects in the same upper left lung segment, which stayed the same over the duration of the seven year study. Credit: Schulich Medicine & Dentistry

These studies deepen our understanding of asthma and also open up opportunities for personalized therapies that can target specific areas of the lungs. In a study published recently in the journal Radiology, researchers used a specialized MRI technique developed at Western's Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, to follow 11 patients with mild to moderate asthma over a six year period and were able to visualize where air goes in the lungs and more importantly, where it does not.

These pockets of the lungs where there is no fresh air are called ventilation defects, and researchers and clinicians have long thought that these defects are random, wide-spread and change their location in the lungs depending on a number of factors in patients with asthma.

These studies refute that long-standing belief.

“Most of the patients in our study had essentially the same ventilation defects at the first visit and six years later both in terms of size and spatial location in the lungs,” said Rachel Eddy, PhD

Candidate at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry and lead author on the studies. “This tells us that there are focal regions inside the lungs that are abnormal, and these stay that way over time.”

In a case study published today in the journal Chest the researchers used the same technique in a set of twins with asthma. While the twins are non-identical, the researchers found that they actually had identical ventilation defects in the same upper left lung segment, which stayed the same over the duration of the seven year study.

“This result found in twins helps us further understand that asthma is not random, and asthma abnormalities persist over long periods of time in the same lung regions. The airway abnormalities likely have a heritable and environmental component,” said Grace Parraga, PhD, Tier 1 Canada Research Chair, Professor at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry and Scientist at Robarts Research Institute.

This finding emphasizes the importance of personalized and image-guided therapy for asthmatic patients. “We see now that patients have different thumbprints of disease, and this points to the need for therapy that is patient-specific,” said Dr. Cory Yamashita, Associate Professor of Respirology at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry.

The researchers also looked at how the MRI ventilation defects predict those patients that transition from asthma to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which does not respond to treatments that help open up closed airways. This novel finding supports previous health care database results and is critical because COPD patients experience constant and persistent shortness of breath and require more hospital-based care and much worse outcomes.

“COPD patients have difficult-to-treat disease – experiencing life-altering acute worsening more frequently and requiring more frequent hospitalizations,” said Parraga. “If we can predict those that transition from asthma to COPD, perhaps we can find new ways to prevent this from happening in the first place. This would save countless health care dollars, decrease hospitalizations, and improve quality of life and disease control in patients.”

###

Both studies were funded through grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

MEDIA CONTACT: Crystal Mackay, Media Relations Officer, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, Western University, t. 519.661.2111 ext. 80387, c. 519.933.5944, crystal.mackay@schulich.uwo.ca @CrystalMackay

ABOUT WESTERN

Western University delivers an academic experience second to none. Since 1878, The Western Experience has combined academic excellence with life-long opportunities for intellectual, social and cultural growth in order to better serve our communities. Our research excellence expands knowledge and drives discovery with real-world application. Western attracts individuals with a broad worldview, seeking to study, influence and lead in the international community.

ABOUT THE SCHULICH SCHOOL OF MEDICINE & DENTISTRY

The Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at Western University is one of Canada's preeminent medical and dental schools. Established in 1881, it was one of the founding schools of Western University and is known for being the birthplace of family medicine in Canada. For more than 130 years, the School has demonstrated a commitment to academic excellence and a passion for scientific discovery.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

Going Steady—Study Reveals North Atlantic’s Gulf Stream Remains Robust

A study by the University of Bern and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the USA concludes that the ocean circulation in the North Atlantic, which includes the Gulf Stream,…

Single-Celled Heroes: Foraminifera’s Power to Combat Ocean Phosphate Pollution

So-called foraminifera are found in all the world’s oceans. Now an international study led by the University of Hamburg has shown that the microorganisms, most of which bear shells, absorb…

Humans vs Machines—Who’s Better at Recognizing Speech?

Are humans or machines better at recognizing speech? A new study shows that in noisy conditions, current automatic speech recognition (ASR) systems achieve remarkable accuracy and sometimes even surpass human…