Playing tag with the genome

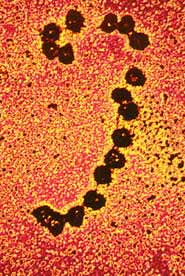

Joining the dots: mRNA (thin thread) snippets reveal new genes. <br>© SPL

A new way to find genes and map disease.

A new technique should aid the hunt for genes in the human genome sequence. The method, which tracks only switched-on genes in cells, will help researchers to distinguish between diseased and normal tissues, and could point the way to new treatments.

Andrew Simpson, of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research in Sao Paulo, Brazil, and colleagues have produced a whopping 700,000 DNA tags, representing the genes that are active in 24 normal and cancerous tissues1.

The team estimates that their set of tags covers about 60 per cent of all human genes. The tags are taken from ’messenger RNA’ transcripts – templates for protein production that are made when a gene is in action.

Experimental approaches such as this are upping estimates of the total number of human genes from the computer-generated figure of 30,000 trumpeted earlier this year. “We’ve got good evidence for 50,000-60,000 genes in the human genome,” says Simpson, adding that laboratory work is “the only real way to identify genes”.

Over one-third of the 700,000 tags seem to come from previously unidentified genes. The team has also identified some genes that are selectively active in cancer cells. Such methods are giving us “a much more precise molecular definition of different cell types, be they normal or diseased”, says genomics researcher Robert Strausberg of the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland.

Transcript analyses reveal differences between apparently identical tumours. “You can’t tell under the microscope that these are different cancers, but you can look at the transcripts and tell them apart,” says Strausberg. “You could use this information in developing new drugs and doing clinical trials.”

The new technique is particularly good at extracting information from the centre of messenger RNAs, where a gene’s function often resides. It is also good at spotting rare transcripts among the 300,000 in any cell. These, Simpson believes, are more likely to be specific to particular tissues.

Every tissue will have its own set of activated genes – its ’transcriptome’ – which will also vary over time. Labs around the world are using different techniques to map the transcriptome for different tissues. “In many ways it’s a more challenging goal than the human genome,” says cancer researcher Victor Velculescu of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

References

- Camargo, A. A. et al. The contribution of 700,000 ORF sequence tags to the definition of the human transcriptome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 98, 12103 – 12108, (2001).

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.nature.com/nsu/011011/011011-5.htmlAll latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

A ‘language’ for ML models to predict nanopore properties

A large number of 2D materials like graphene can have nanopores – small holes formed by missing atoms through which foreign substances can pass. The properties of these nanopores dictate many…

Clinically validated, wearable ultrasound patch

… for continuous blood pressure monitoring. A team of researchers at the University of California San Diego has developed a new and improved wearable ultrasound patch for continuous and noninvasive…

A new puzzle piece for string theory research

Dr. Ksenia Fedosova from the Cluster of Excellence Mathematics Münster, along with an international research team, has proven a conjecture in string theory that physicists had proposed regarding certain equations….