Looking at linkers helps to join the dots

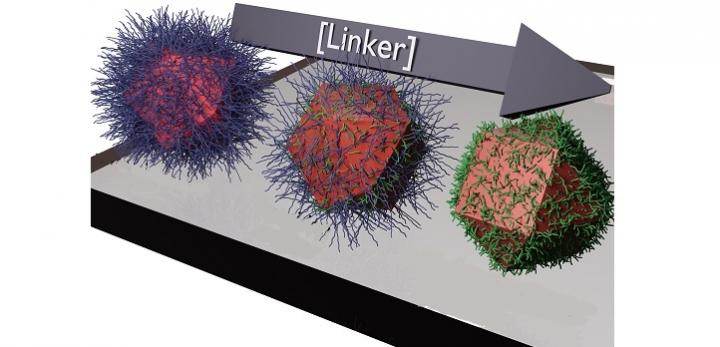

In the solvent-dominated regime, the dots are capped with long oleic acid molecules, which hamper the flow of electricity. After the transition, these are replaced by linker molecules, allowing the dots to conduct electricity efficiently. From left to right is the solvent-dominated regime, the transition regime and the linker-dominated regime. Credit: © 2020 Ahmad R. Kirmani

Just billionths of a meter across, quantum dots are routinely prepared in solution and coated or sprayed as an ink to create a thin electrically conducting film that is used to make devices. “But finding the best way to do this has been a matter of trial and error,” says material scientist Ahmad R. Kirmani.

Now, with colleagues at KAUST and the University of Toronto, Canada, he has revealed why certain well-known techniques can dramatically improve the film's performance.

Quantum dots absorb and emit different wavelengths of light depending on their size. This means they can be tuned to be highly efficient absorbers in solar panels, or to emit different colors for a display, just by making the crystals bigger or smaller.

The dots are commonly grown from lead and sulfur in solution. Because the dots' properties depend on their size, their growth must be halted at the right point, which is done by adding special molecules to cap their growth. Engineers often use molecules of oleic acid, each with 18 carbon atoms, which attach to the crystal's surface, like hairs, blocking growth.

This creates a solution of dots suitable for coating to create a film. Yet, this film is not good at conducting electricity because the long acid molecules hamper the flow of electrons between nanocrystals. So engineers add shorter molecules.

These “linkers” only have around two carbon atoms per molecule. The linkers replace the long capping molecules, increasing conductance. “The method has been used for a couple of decades, but nobody had investigated exactly what happens,” says Kirmani.

To find out, Kirmani's team used a microbalance to monitor the exchange of oleic acid for linkers during the transition. They measured the spacing between the dots by scattering X-rays from them, and they also recorded the film's changing thickness, density and optical absorption characteristics.

Rather than seeing a smooth change in the film's properties, they saw a sudden jump–marking a phase transition. When roughly all the acid molecules have been displaced by linkers, the dots abruptly come close together, and the conductivity shoots up.

Kirmani hopes other teams will be inspired to investigate further, possibly by arresting the transition process somewhere midway and introducing various molecules to the dot surface to see what novel features emerge. “There is a lot of potential in taking this understanding to new paradigms for new technologies,” he says.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Materials Sciences

Materials management deals with the research, development, manufacturing and processing of raw and industrial materials. Key aspects here are biological and medical issues, which play an increasingly important role in this field.

innovations-report offers in-depth articles related to the development and application of materials and the structure and properties of new materials.

Newest articles

Pinpointing hydrogen isotopes in titanium hydride nanofilms

Although it is the smallest and lightest atom, hydrogen can have a big impact by infiltrating other materials and affecting their properties, such as superconductivity and metal-insulator-transitions. Now, researchers from…

A new way of entangling light and sound

For a wide variety of emerging quantum technologies, such as secure quantum communications and quantum computing, quantum entanglement is a prerequisite. Scientists at the Max-Planck-Institute for the Science of Light…

Telescope for NASA’s Roman Mission complete, delivered to Goddard

NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is one giant step closer to unlocking the mysteries of the universe. The mission has now received its final major delivery: the Optical Telescope…