Stability despite perturbation – a tale of neural circuits

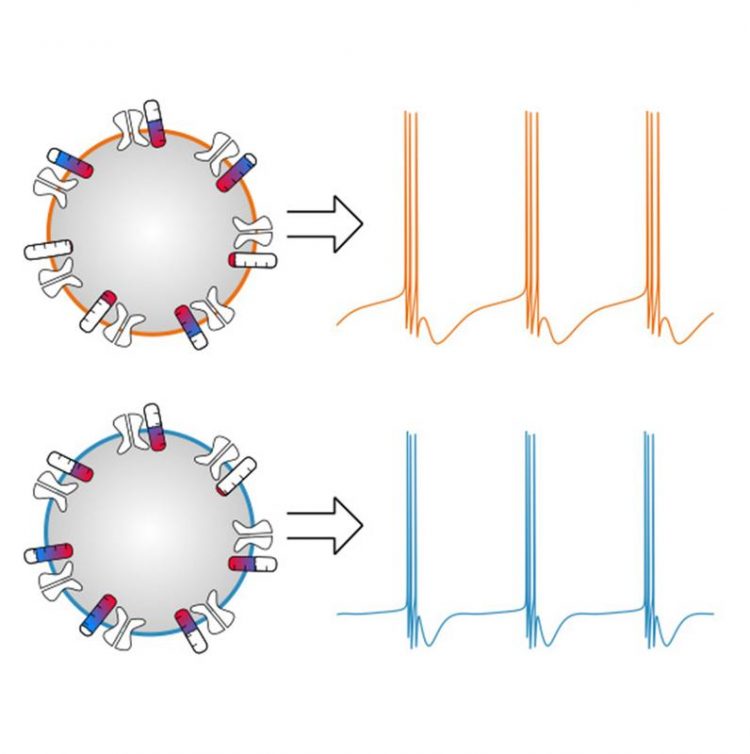

Two model neurons (left) can show similar firing pattern (right) despite differences in the individual levels of ion channel expression. This notion is termed “degeneracy”. Max-Planck-Institut für Hirnforschung

A neural circuit comprises a population of nerve cells (neurons) interconnected by synapses. Once activated, these units carry out specific functions that result in different behaviors. Neural circuits of animals within the same species can display huge differences in the properties of their components: the neurons and the synapses.

However, these circuits still reliably fulfill the same function with nearly identical output, for instance generate a certain behavior. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research in Frankfurt have now used a single property, the phase difference of a rhythmic model circuit, to show that perturbations can reveal the underlying differences between different implementations of seemingly identical circuits.

Using computational models, the scientists studied neurons with biologically measured ion channel conductances, enabling them to expose relationships between specific conductances that play an essential role in circuit stability after perturbation.

Neural circuits among different animal species are made up of the same types of neurons and synapses though they may differ in arrangement and strength. Yet, they enable each individual to perform a given behavior equally well – a property that has been called “degeneracy”.

This is especially the case for innate (rather than learned) behaviors that are critical for the survival of the animal. Examples of these include rhythmic behaviors like breathing and locomotion in humans or the digestion of food by the nervous system in the stomach of crabs and lobsters.

In a new computational study, Max Planck Research Group Leader Dr. Julijana Gjorgjieva and Ph.D. student Sebastian Onasch use one of the simplest circuits, called a half-center oscillator, that consists of two neurons mutually coupled with inhibition to determine what can be said about the properties of the circuits only by examining the output of the circuit.

This circuit is known to generate alternating activity, where only one neuron is active at a time, rhythmically switching to the other one. The rhythmic output of the circuit can be well described by the phase difference, a characteristic that determines the regularity of the activation of the two constituent neurons.

“In order to find the rules that underlie stable circuits we asked ourselves ‘what can we do with a single measurement that is fairly easy to obtain experimentally, such as the phase difference between two neurons’? We were surprised by the result”, explains Onasch.

The scientists first generated a large population of such model circuits consisting of neurons with biologically determined parameters. Specifically, they used a Hodgkin-Huxley neuron model with multiple intrinsic conductances measured in the nervous system of the stomach of crabs and lobsters, which can give rise to very different firing patterns of the individual neurons and circuits.

However, they found that many of these circuits actually had the same firing pattern even though the intrinsic conductances were different. The scientists then induced perturbations either from the environment or intrinsic challenges and found that these circuits responded differently – and they could quantify exactly how they differed by using statistical and machine learning techniques.

“We found that stable circuit output results from correlations between specific neuronal conductances generated by particular channel types but not others”, explains Gjorgjieva.

“Rather than studying the stability of circuits with prescribed conductance relationships, we approached the problem in reverse: starting from the stability to a given perturbation, we revealed conductance relationships of the circuit’s constituent neurons that similarly affect circuit stability when perturbed. This revealed surprising conductance combinations that could even predict the response to specific perturbations.”

“Our work identifies the conditions for the emergence of stable and robust circuit output from variable circuit elements. This has important implications for drug design and reliable neuromodulatory control”, concludes Gjorgjieva.

This work was funded by the Max Planck Society.

Dr. Julijana Gjorgjieva, Computation in Neural Circuits Group, Max Planck Institute for Brain Research, gjorgjieva@brain.mpg.de, +49 69 850033 3600

Sebastian Onasch and Julijana Gjorgjieva. Circuit stability to perturbations reveals hidden variability in the balance of intrinsic and synaptic conductances. Journal of Neuroscience 16 March 2020, JN-RM-0985-19; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0985-19.2020

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

New theory reveals the shape of a single photon

A new theory, that explains how light and matter interact at the quantum level has enabled researchers to define for the first time the precise shape of a single photon….

Perovskite research boosts solar cell efficiency and product life

An international team led by the University of Surrey with Imperial College London have identified a strategy to improve both the performance and stability for solar cells made out of…

Neuroscientists discover how the brain slows anxious breathing

Salk scientists identify brain circuit used to consciously slow breathing and confirm this reduces anxiety and negative emotions. Deep breath in, slow breath out… Isn’t it odd that we can…