Improved remote mapping of disaster zones

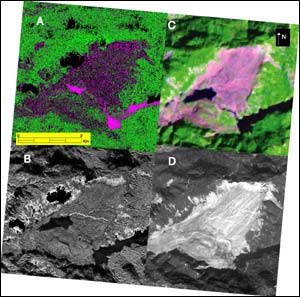

Comparison of various types of remote sensing data over the Tsaoling landslide within 18 months of the September 1999 magnitude 7.6 Chi Chi earthquake in central Taiwan. <br> <br>a) Surface classification map made from radar scattering mechanisms obtained through analysis of airborne L-band (0.25 m wavelength) Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) polarimetry (obtained September 27, 2000). Purple = bare surface, green = forest, black = other (including missing data). <br> <br>b) Grayscale C-band (0.06 m wavelength) image of vertically-polarized backscatter SAR intensity (obtained September 27, 2000). <br> <br>c) False-color image of Landsat 7 Thematic Mapper (TM) data (February 2001). Green areas are forested, the purple areas are the landslide source area and debris apron, dark areas in the lower half of image are lakes impounded by landslide. Vegetation regrowth is occurring on the debris apron 18 months after the landslide. Compare with radar classification map in a), <br> <br>d) Indian Research Satellite visible band panchromatic data (October 31, 1999) obtained within six weeks of the landslide. The landslide is the light colored

Columbia researchers develop “fingerprinting” techniques for SAR mapping

Research by scientists at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University shows that Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) polarimetry is a more superior technology for rapidly identifying disaster zones than the currently used optical remote sensing technologies, such as Landsat and SPOT. Their findings are published in the Journal of Geophysical Research, and coincide with an opportunity to outfit satellites scheduled for deployment in 2004 with SAR polarimetry instruments.

Rapidly assessing land damage and responding to natural disasters is key to saving lives. SAR mapping has a clear advantage over optical mapping-the results are not hindered by darkness, clouds, or the smoke and dust frequently associated with disaster zones. This new SAR research marks the initial step in developing radar-based maps of damaged landscapes that can be rapidly provided to rescue workers.

Kristina Czuchlewski and Jeffrey Weissel, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University, and Yunjin Kim, Jet Propulsion Laboratory at California Institute of Technology, have developed a classification system for turning the data acquired by SAR into detailed maps depicting landscape elements such as water, vegetation, rocks, and elevations on a per-pixel basis (i.e. for areas as small as 5 x 5 m).

Czuchlewski et al. evaluated the effectiveness of using SAR polarimetry by mapping the massive Tsaoling landslide that resulted from the 1999 earthquake (magnitude 7.6) in Taiwan, damaging highway transportation systems and isolating communities in the area. The Tsaoling landslide slid into the Chingshuichi Valley killing 34 people and requiring rapid construction of a new road to facilitate rescue efforts. Debris covered about 1.3 square miles of the Valley floor, damming the river and forming an artificial lake that had to be drained to avoid the possibility of dam failure during the monsoon rains.

“Our SAR polarimetry data was taken one year after the Tsaoling landslide occurred. When you compare this map to the one generated from the Landsat optical data just 5 months after ours, we find SAR polarimetry to be equally proficient, with the critical added advantage of not needing clear skies to get an image,” said Kristina Czuchlewski, Doctoral Candidate, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Columbia University.

The researchers currently utilize NASA’s AIRSAR DC-8 aircraft to collect SAR polarimetry data. Electromagnetic energy is transmitted from the air to the disaster zone and measures the electric field backscatter. This backscatter is then further processed to determine scattering mechanisms, or the “fingerprint,” of the surface materials. The different types of scattering mechanisms are applied to the various elements of the terrain. For example, backscatter from bare, rough surfaces generally consists of a single “bounce” back toward the receiving antenna. In contrast, backscatter from leafy trees is diffuse, becoming more random as the radar wave interacts with the trunks, branches and leaves of the canopy. These fundamental properties of the surface can be easily extracted from fully-polarimetric SAR because this type of data records the amplitude and phase of the backscattered electric field, allowing us to measure the organized and random bounces occurring within each pixel. Optical imagery, on the other hand, detects these different surface cover types based on their electromagnetic signature at very short wavelengths. Instead of scattering, optical techniques measure reflectance, a property that is strongly disturbed by the atmosphere and dependent on the sun’s energy.

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory researchers are also conducting studies to apply SAR polarimetry mapping to other natural disaster sites, including those devastated by wildfires and lava flows.

“If carried aboard a fleet of robotic, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) instead of on satellites, SAR polarimeters could be rapidly deployed in a cost effective way to disaster sites anywhere on the globe. We could take advantage of the long endurance of UAVs to monitor the development of emerging disasters such as floods, wildfires and volcanic eruptions. In this way, SAR-based disaster response technology could play a vital role in evacuating populations placed at risk by many different kinds of natural disasters,” said Jeffrey Weissel, Doherty Senior Scholar and leader of the research team at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

The Tsaoling landslide research was supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Solid Earth & Natural Hazards program and an Earth System Science Fellowship award.

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory

The Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, a member of The Earth Institute at Columbia University, is one of the world’s leading research centers examining the planet from its core to its atmosphere, across every continent and every ocean. From global climate change to earthquakes, volcanoes, environmental hazards and beyond, Observatory scientists provide the basic knowledge of Earth systems needed to inform the future health and habitability of our planet. For more information, visit www.ldeo.columbia.edu.

The Earth Institute

The Earth Institute at Columbia University is the world’s leading academic center for the integrated study of Earth, its environment, and society. The Earth Institute builds upon excellence in the core disciplines-earth sciences, biological sciences, engineering sciences, social sciences and health sciences-and stresses cross-disciplinary approaches to complex problems. Through its research training and global partnerships, it mobilizes science and technology to advance sustainable development, while placing special emphasis on the needs of the world’s poor. For more information, visit www.earth.columbia.edu.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Information Technology

Here you can find a summary of innovations in the fields of information and data processing and up-to-date developments on IT equipment and hardware.

This area covers topics such as IT services, IT architectures, IT management and telecommunications.

Newest articles

Innovative 3D printed scaffolds offer new hope for bone healing

Researchers at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia have developed novel 3D printed PLA-CaP scaffolds that promote blood vessel formation, ensuring better healing and regeneration of bone tissue. Bone is…

The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease

ASU- and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute-led study implicates link between a common virus and the disease, which travels from the gut to the brain and may be a target for antiviral…

Molecular gardening: New enzymes discovered for protein modification pruning

How deubiquitinases USP53 and USP54 cleave long polyubiquitin chains and how the former is linked to liver disease in children. Deubiquitinases (DUBs) are enzymes used by cells to trim protein…