DWI scientists program the lifetime of self-assembled nanostructures

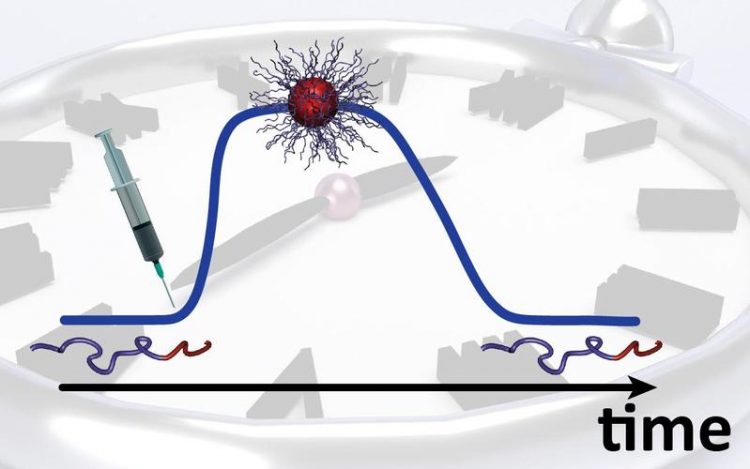

Scientists at DWI can program self-assembly, lifetime and degradation of nanostructures, consisting of single polymer strands. Image: Thomas Heuser / DWI

Dr. Andreas Walther, research group leader at DWI – Leibniz Institute for Interactive Materials in Aachen, developed an aqueous system that uses a single starting point to induce self-assembly formation, whose stability is pre-programmed with a lifetime before disassembly occurs without any additional external signal – hence presenting an artificial self-regulation mechanism in closed conditions.

Biologically inspired principles for synthesis of complex materials are one of Andreas Walther’s key research interests. To allow the preparation of very small, elaborate objects, nanotechnology uses self-assembly.

Usually, in man-made self-assemblies, molecular interactions guide tiny building blocks to aggregate into 3D architectures until equilibrium is reached. However, nature goes one step further and prevents certain processes from reaching equilibrium.

Assembly competes with disassembly, and self-regulation occurs. For example, microtubules, components of the cytoskeleton, continuously grow, shrink and rearrange. Once they run out of their biological fuel, they will disassemble.

This motivated Andreas Walther and his team to develop an aqueous, closed system, in which the precise balance between assembly reaction and programmed activation of the degradation reaction controls the lifetime of the materials.

A single starting injection initiates the whole process, which distinguishes this new approach from current responsive systems that always require a second signal to trigger the disassembly.

The approach uses pH changes to control the process. The scientists press the start button by adding a base and a dormant deactivator.

This first rapidly increases the pH and the building blocks – block copolymers, nanoparticles or peptides – then assemble into a three-dimensional structure. At the same time, the change of pH stimulates the dormant deactivator.

PhD student Thomas Heuser explains: “The dormant deactivator slowly becomes activated and triggers an off-switch. But it takes a while before the off-switch unfolds its full potential. Depending on the molecular structure of the deactivator, this can be minutes, hours or a whole day. Until then, the self-assembled nanostructures remain stable.”

Currently a hydrolytic reaction is used to activate the dormant deactivator. However, Andreas Walther and his team are already working on more sophisticated versions, which include an enzymatic reaction to slowly start the self-destruction mechanism.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.dwi.rwth-aachen.deAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

NASA: Mystery of life’s handedness deepens

The mystery of why life uses molecules with specific orientations has deepened with a NASA-funded discovery that RNA — a key molecule thought to have potentially held the instructions for…

What are the effects of historic lithium mining on water quality?

Study reveals low levels of common contaminants but high levels of other elements in waters associated with an abandoned lithium mine. Lithium ore and mining waste from a historic lithium…

Quantum-inspired design boosts efficiency of heat-to-electricity conversion

Rice engineers take unconventional route to improving thermophotovoltaic systems. Researchers at Rice University have found a new way to improve a key element of thermophotovoltaic (TPV) systems, which convert heat…