Formation of complex biomolecules from simple biochemical building blocks

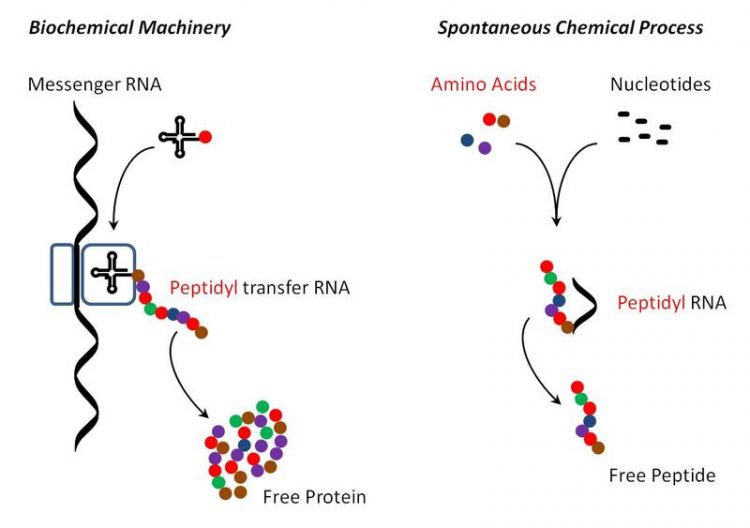

Cartoon representations of biochemical protein synthesis (left) and the spontaneous chemical processes found in the laboratory. (Graphic by M. Jauker)

Life is based on a complex biochemical machinery. How this machinery arose from inanimate material is unclear. The most important biochemical machines are enzymes (proteins). The blueprints of the enzymes are encoded in DNA and are transcribed with the aid of both RNA and enzymes.

Without enzymes, there is no transcription, and without genes and RNA there are no enzymes. Up to now the solution for this dilemma was presumed to be that a so-called 'RNA world' was first, in which RNA acted both as a genetic material and as biocatalyst. Yet, how the 'RNA-protein world' evolved from the RNA world was unclear.

Unexpected observation: formation of peptidyl RNAs

Researchers at the University of Stuttgart now report that spontaneous reactions take place between the basic building blocks of RNA, the ribonucleotides, and amino acids, if they come into contact with each other in a special aqueous buffer.

The buffer contains a condensation agent that induces a spontaneous condensation of the building blocks. Not just RNA chains form in the mixtures, but also mixed molecules, made up of an RNA portion and a peptide chain (proteins are long peptide chains). This mixed type of molecule is called peptidyl RNA. Certain parts of the biochemical machinery for protein synthesis may have evolved from peptidyl RNAs.

The observation came as a surprise. The research group of Professor Clemens Richert was searching for reaction conditions inducing enzyme-free copying of RNA sequences. When graduate student Mario Jauker used conditions mimicking ice-water mixtures that are found when seawater freezes and he added a potent condensation agent, he observed untemplated formation of new RNA chains

. Since the condensation agent, an organic derivative of the molecule cyanamide, is also used in peptide synthesis, chemical engineer Helmut Griesser then mixed amino acids to the RNA building blocks. Surprisingly, significant concentrations of peptidyl RNAs formed alongside RNA chains and some free peptides in the salty buffer solutions. More complex peptidyl RNAs are key intermediates of protein synthesis.

Cartoon representations of biochemical protein synthesis (left) and the spontaneous chemical processes found in the laboratory. Peptidyl RNAs arise from amino acids and nucleotides, which release peptides in the presence of acid. (Graphic by M. Jauker)

In today's protein synthesis (left-hand side of graphic), the peptide chain grows to a full-length protein by migrating from one charged transfer-RNA to the next, with one amino acid residue being added during each step according to the genetic code. Earlier attempts to induce the formation of peptidyl RNAs in the absence of enzymes were largely unsuccessful. It was believed that the so-called 'C-terminus' of the peptide chain and the phosphate group of the first ribonucleotide reacted with each other.

A detailed structural characterization at the Institute of Organic Chemistry, revealed that the 'N-terminus' of the peptide chain is linked to the phosphate instead. This explains why longer peptidyl RNAs were able to form, as this structural arrangement allows both the peptide chain and the RNA chain to grow simultaneously. When the scientists added acetic acid, fee peptides were released from the peptidyl RNAs.

Importantly, it is not just peptidyl RNAs that form in the aqueous condensation buffer employed. After adding other building blocks, the researchers were able to also detect compounds that play an important role in the metabolism of the cell. These include adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the 'energy currency' of the cell, as well as the cofactors NAD and FAD that are involved in the biosynthesis of many cellular components, as well as the energy metabolism of the cell.

A more conclusive picture emerges

It is now clear that under the same reaction conditions, simple genetic materials, peptides, and key molecules of a primitive metabolism can form from simple building blocks. Therefore no major evolutionary step appears to be necessary to get from an 'RNA world' to an 'RNA-protein world'. The latter may have evolved in a series of spontaneous steps via reactions that are related to those that lead to the formation of RNA chains. The observation that this happens under conditions that also lead to the spontaneous copying of genetic information makes these observations all the more fascinating. As Professor Richert put it: “It felt as if we were watching a play performed by molecules. A play that nature encoded by creating matter with properties more fascinating than the simple structure of the chemicals suggests.” His team, that now also includes Svenja Kaspari, is currently working on reaction conditions that are closer to those that are found in the cell today.

Publications in the international edition of “Angewandte Chemie”

The Stuttgart researchers report the results of their studies in two publications that are being published in the journal Angewandte Chemie and that are accessible online without a subscription:

Mario Jauker, Helmut Griesser and Clemens Richert: “Copying RNA sequences without pre-activation”, Angewandte Chemie International Edition (2015), DOI: 10.1002/anie.201506592 and “Spontaneous formation of RNA strands, peptidyl-RNA and co-factors”, Angewandte Chemie International Edition (2015),: DOI: 10.1002/anie.201506593

Online-Versions:

https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201506592 and https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201506593

Contact:

Professor Clemens Richert, University of Stuttgart, Institute of Organic Chemistry, Tel. 0711/685-64311, Email: lehrstuhl-2 (at) oc.uni-stuttgart.de

Andrea Mayer-Grenu, University of Stuttgart, Abt. University Communication, Tel. 0711/685-82176, Email: andrea.mayer-grenu (at) hkom.uni-stuttgart.de

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.uni-stuttgart.de/All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

An Endless Loop: How Some Bacteria Evolve Along With the Seasons

The longest natural metagenome time series ever collected, with microbes, reveals a startling evolutionary pattern on repeat. A Microbial “Groundhog Year” in Lake Mendota Like Bill Murray in the movie…

Witness Groundbreaking Research on Achilles Tendon Recovery

Achilles tendon injuries are common but challenging to monitor during recovery due to the limitations of current imaging techniques. Researchers, led by Associate Professor Zeng Nan from the International Graduate…

Why Prevention Is Better Than Cure—A Novel Approach to Infectious Disease Outbreaks

Researchers have come up with a new way to identify more infectious variants of viruses or bacteria that start spreading in humans – including those causing flu, COVID, whooping cough…