New insight into how plant cells divide

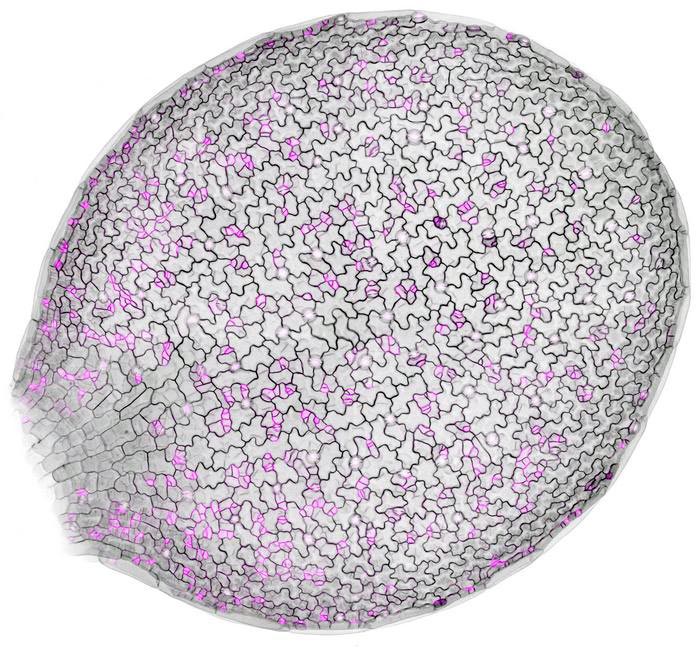

An image of a developing leaf from an Arabidopsis plant that has been modified to express fluorescent proteins marking the cell boundaries (black) and a polarity protein (magenta). This technology allowed the authors to study protein dynamics within the stem cells of living plants.

Credit: Andrew Muroyama

Every time a stem cell divides, one daughter cell remains a stem cell while the other takes off on its own developmental journey. But both daughter cells require specific and different cellular materials to fulfill their destinies.

Animal stem cells use the cytoskeleton – a transient network of structural tubules – to physically pull the correct materials from the parent cell into each daughter cell during the split. Plants also have stem cells that need to distribute different materials to each of their daughters, but earlier studies seem to have ruled out an “animal-style” cytoskeleton to accomplish this task. And what plants used instead remained elusive – until now.

In a new study published July 6 in Science, researchers at Stanford University found that plant cells also use the cytoskeleton. But there’s a twist. Instead of pulling on the cytoskeleton, like animal stem cells, the plant cells they studied actually pushed it away.

“Instead of using the cytoskeleton to say, ‘Divide this way!’ the plants said, ‘DON’T divide this way!’ ” said Andrew Muroyama, a former postdoctoral fellow at Stanford, currently an assistant professor at the University of California, San Diego, and the lead author of the paper.

The new finding could help researchers to engineer plants that are more adaptable to changing environments – a critical task as the world continues to face climate change.

“Understanding how stem cells divide in animals has been important for understanding various human diseases and has impacted translational medicines,” said Muroyama. “I have a similar hope that improving our understanding of how stem cells divide in plants might inform engineering applications in the future.”

Blocking wall construction by threatening catastrophe

Researchers in the lab of Dominique Bergmann, the Shirley R. and Leonard W. Ely, Jr. Professorship in the School of Humanities and Sciences professor of biology, began this work by investigating polarity complexes – little clusters of proteins that are critical in each cell to build leaves of the proper size and shape. Polarity complexes help dividing leaf stem cells orient themselves. “Stem cells use these polarity proteins to decide where to divide,’ ” said Muroyama. “We knew those proteins were involved in division, but we didn’t know how they controlled the process at the molecular level.”

To investigate how these proteins work, the team developed plant cell lines that expressed fluorescent versions of polarity complex and cytoskeletal proteins, then spent hundreds of hours in a dark room, tracking the glowing proteins’ movements while cells grew, divided, and repeated.

They soon observed that some cells weren’t dividing according to the “shortest wall rule,” which normally governs plant cell division. While plant cells are expected to build the smallest – and therefore most energetically conservative – walls possible to divide cells, in some cases, the polarity complex was located right where that wall would need to be built. Somehow, it blocked construction. Through a series of rigorous experiments, the researchers concluded that the polarity complex was pushing away the microtubules that would otherwise enable the construction of the wall.

“The polarity complex was like, ‘If any of you microtubules try to encroach on my region, I’m going to force you away. I’ll literally cause a catastrophe – that’s the technical term for completely disrupting microtubules – so you can’t invade this zone,’ ” said Bergmann.

Management for a changing climate

Bergmann’s lab is interested in resilience – how plants cope with changing environments. Plants survive by changing their leaves or their branch patterns, or the rates at which they respire or store sugars.

“This research could lead to applications where stem cell behavior could be tuned, for example, to alter plant architecture, or to help plants adjust to a changing climate,” said Muroyama.

Decisions about how to respond to signals from the environment are directed by stem cells. Within this process, Bergmann compares the polarity complex to a construction manager, giving the directions that ensure the stem cell splits properly.

“This construction manager receives signals from the environment, decides what to do, and tells the cell, ‘Yes, you should divide.’ But then it also says, ‘Now you’ve divided. Go off and seek your fortune,’ ” said Bergmann.

Now that the researchers know how this manager works, they can determine its role in upstream and downstream processes – and figure out ways to harness its power.

“Exactly how the polarity complex works is something we still need to figure out,” said Bergmann. “How do you get all these plants that make really cool specialized cells – cells that make interesting shapes, cells that make interesting chemicals, cells that respond to certain stimuli? And can we engineer that to happen?”

Yan Gong, PhD ’21, and Kensington Hartman, a staff research associate at the University of California, San Diego are co-authors of this work. Bergmann is also a member of Stanford Bio-X and the Stanford Cancer Institute, and an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI).

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, University of California, San Diego, Stanford University, and HHMI.

Journal: Science

DOI: 10.1126/science.add6162

Article Title: Cortical polarity ensures its own asymmetric inheritance in the stomatal lineage to pattern the leaf surface

Article Publication Date: 7-Jul-2023

Media Contacts

Taylor Kubota

Stanford University

tkubota@stanford.edu

Mario Aguilera

University of California, San Diego

maguilera@ucsd.edu

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Innovative 3D printed scaffolds offer new hope for bone healing

Researchers at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia have developed novel 3D printed PLA-CaP scaffolds that promote blood vessel formation, ensuring better healing and regeneration of bone tissue. Bone is…

The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease

ASU- and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute-led study implicates link between a common virus and the disease, which travels from the gut to the brain and may be a target for antiviral…

Molecular gardening: New enzymes discovered for protein modification pruning

How deubiquitinases USP53 and USP54 cleave long polyubiquitin chains and how the former is linked to liver disease in children. Deubiquitinases (DUBs) are enzymes used by cells to trim protein…