(Re)-acquiring the potential to become everything

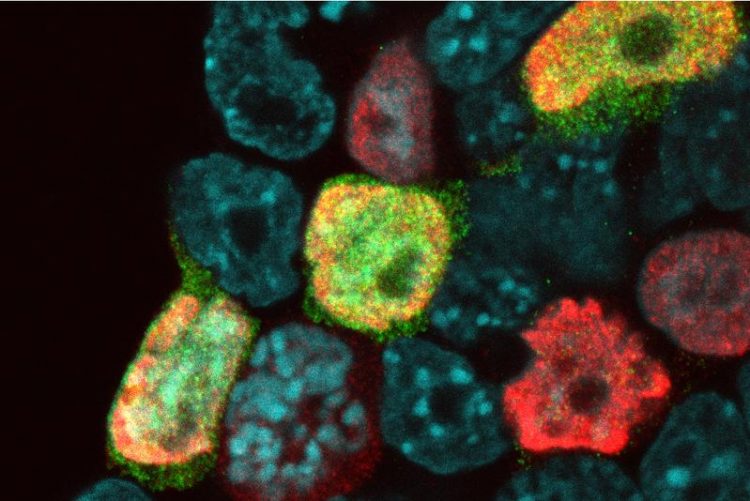

Fluorescence image of mouse embryonic stem cells (nuclei in blue) including 2 cell-like cells (green) and the novel population of transitioning cells (red). Source: Helmholtz Zentrum München/IES

Cellular plasticity is the ability of a cell to make different cell types. At the early stages of life, the fertilized single-cell coming from the mother’s egg and the father’s sperm is highly plastic – it will give rise to all of the cell types of the body. Cellular plasticity is therefore essential for multicellular organisms like humans to exist.

The single fertilized cell first divides into two cells (referred to as the 2-cell stage of development). The single cell and the two cells resulting from it, have the highest level of cellular plasticity: They are totipotent, which means they can make a full organism, including the extra-embryonic placental tissue. In contrast, embryonic stem cells are pluripotent which means they can make all the cells of the organism, but typically not the extra-embryonic tissue.

In a culture of embryonic stem (ES) cells, a small population (around 1%) spontaneously turns into cells that are similar to the totipotent cells of the 2-cell stage embryo. These cells are called 2-cell-like cells (2CLCs). In this study, Prof. Dr. Maria Elena Torres-Padilla’s team set out to determine the specific molecular nature of these cells and find out how they come to be.

Torres-Padilla is director of the Institute of Epigenetics and Stem Cells (IES) at Helmholtz Zentrum München and professor of Stem Cell Biology at the LMU. The aim of the team was to gain insights in to the molecular features of totipotency and to work out how changes in cellular plasticity may occur. Their ultimate goal is to understand how these totipotent-like cells ‘behave’ so that they can manipulate them, and generate them in vitro.

The team began by comparing the genes expressed in ES cells to those expressed in 2CLCs. To do this they used ES cells which express a green fluorescent protein when cells start expressing the MERVL gene. “MERVL is a retrotransposon expressed in 2-cell-like cells” explains Diego Rodriguez-Terrones, a PhD student in the Torres-Padilla lab and co-first author of the paper.

“Using this cell line allows us to separate 2-cell-like cells from the ES cells in the culture by collecting the green cells which have entered the 2-cell like state. We then compare the genes expressed in both cell types” he adds. This single cell transcriptome analysis followed by computational analyses enabled the team to identify the gene expression profiles of cells in the process of changing from ES cells to 2CLCs.

They found that during the transition period, cells expressed increasing amounts of a gene encoding the transcription factor Zscan4. They developed their reporter line to also be able to express a red fluorescent protein when Zscan4 is expressed. Live cell imaging confirmed that the majority of cells became red (Zscan4 positive) before becoming green (MERVL positive 2-cell-like cells).

“This observation, combined with the transcriptomic data, told us that cells transition through an intermediate state before becoming 2-cell-like cells” said Maria Elena Torres-Padilla. “Based on these seemingly ordered changes in gene expression, we wanted to find out what might be driving the emergence of the 2-cell-like state. This information would be crucial for furthering our knowledge concerning key regulators of cellular plasticity”.

With the goal of identifying chromatin regulators that can promote cellular reprogramming, the team performed an siRNA screen, in which the expression of over 1000 genes was impaired to see how the appearance of 2CLCs was affected. “The results of this screen were extraordinary, because we identified many novel proteins that regulate the emergence of 2CLCs” said Dr. Xavier Gaume, co-first author of the paper and postdoc in the Torres-Padilla lab.

Of particular interest was the observation that reducing levels of a specific chromatin factor (Ep400/Tip60), results in more 2CLCs. As Ep400/Tip60 is involved in chromatin compaction, this observation identifies an interesting link between chromatin ‘openness’ with increased potency.

Further Information

Background:

Recently, the same Torres-Padilla team published another study in ‘Nature Genetics’ demonstrating that the expression of retrotransposons plays an important role in embryonic development. Since this is also depending on the chromatin ‘openness’, this might support the new observations. The doctoral student Diego Rodriguez-Terrones participates in the Helmholtz Graduate School for Environmental Health (HELENA).

Original Publication:

Rodriguez-Terrones, D. & Gaume, X. et al. (2017): A molecular roadmap for the emergence of early-embryonic-like cells in culture. Nature Genetics, DOI: 10.1038/s41588-017-0016-5

The Helmholtz Zentrum München, the German Research Center for Environmental Health, pursues the goal of developing personalized medical approaches for the prevention and therapy of major common diseases such as diabetes and lung diseases. To achieve this, it investigates the interaction of genetics, environmental factors and lifestyle. The Helmholtz Zentrum München is headquartered in Neuherberg in the north of Munich and has about 2,300 staff members. It is a member of the Helmholtz Association, a community of 18 scientific-technical and medical-biological research centers with a total of about 37,000 staff members. http://www.helmholtz-muenchen.de/en

The research of the Institute of Epigenetics and Stem Cells (IES) is focused on the characterization of early events in mammalian embryos. The scientists are especially interested in the totipotency of cells which is lost during development. Moreover, they want to elucidate who this loss is caused by changes in the nucleus. Their main goal is to understand the underlying molecular mechanisms which might lead to the development of new therapeutic approaches. http://www.helmholtz-muenchen.de/ies

As one of Europe's leading research universities, LMU Munich is committed to the highest international standards of excellence in research and teaching. Building on its 500-year-tradition of scholarship, LMU covers a broad spectrum of disciplines, ranging from the humanities and cultural studies through law, economics and social studies to medicine and the sciences. 15 percent of LMU‘s 50,000 students come from abroad, originating from 130 countries worldwide. The know-how and creativity of LMU's academics form the foundation of the University's outstanding research record. This is also reflected in LMU‘s designation of as a “university of excellence” in the context of the Excellence Initiative, a nationwide competition to promote top-level university research. http://www.en.lmu.de

Contact for the media:

Department of Communication, Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Center for Environmental Health (GmbH), Ingolstädter Landstr. 1, 85764 Neuherberg – Phone: +49 89 3187 2238 – Fax: +49 89 3187 3324 – E-mail: presse@helmholtz-muenchen.de

Scientific contact at Helmholtz Zentrum München:

Prof. Dr. Maria Elena Torres-Padilla, Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Center for Environmental Health (GmbH), Institute of Epigenetics and Stem Cells, Marchioninistraße 25, 81377 München – Tel. +49 89 3187 3317 – E-mail: torres-padilla@helmholtz-muenchen.de

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Can lab-grown neurons exhibit plasticity?

“Neurons that fire together, wire together” describes the neural plasticity seen in human brains, but neurons grown in a dish don’t seem to follow these rules. Neurons that are cultured…

Unlocking the journey of gold through magmatic fluids

By studying sulphur in magmatic fluids at extreme pressures and temperatures, a UNIGE team is revolutionising our understanding of gold transport and ore deposit formation. When one tectonic plate sinks…

3D concrete printing method that captures carbon dioxide

Scientists at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) have developed a 3D concrete printing method that captures carbon, demonstrating a new pathway to reduce the environmental impact of the construction…