Purdue researchers expose ’docking bay’ for viral attack

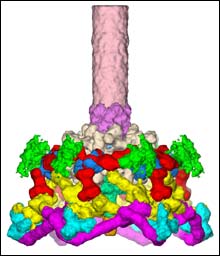

This is a close-up image of the T4 virus baseplate, which the virus uses to attach itself to its E. coli bacterium host. The 16 types of proteins that form the baseplate are color-coded. More than 150 total protein molecules make up the baseplate, a complex molecular machine that changes configuration when it bonds with the E. coli cell membrane. Further analysis of the baseplate could lead to advances in both medicine and nanotechnology. (Graphic/Purdue University Department of Biology)

Imagine a virus and its cellular target as two spacecraft – the virus sporting a tiny docking bay that allows it to invade its victim. Purdue University researchers have taken a close-up picture of one virus’ docking bay, work that could have implications for both medicine and nanotechnology.

Using advanced imaging techniques, an international team of biologists led by Michael Rossmann of Purdue, Vadim Mesyanzhinov in Moscow and Fumio Arisaka at the Tokyo Institute of Technology has analyzed the structure of part of the T4 virus, which commonly infects E. coli bacteria. The part they analyzed, called the baseplate, is a complex structure made of 16 types of proteins that allows T4 to attach itself to the surface of E. coli in order to inject its own deadly genetic material. Their work has produced the clearest picture ever obtained of the baseplate, which plays a critical role in the initial stages of viral infection.

“We now have a fairly complete picture of the baseplate, the part of the virus that latches onto its cellular victim,” said Rossmann, who is Hanley Distinguished Professor of Biological Sciences in Purdue’s School of Science. “Armed with this knowledge, we should obtain a better understanding of how this virus injects its genetic material into its host. It could be the key to stopping the process – or even harnessing it to benefit humanity.”

The paper appears in the latest issue (Sunday, 8/17) of Nature Structural Biology.

While T4 is perhaps not as well known as the viruses that cause the flu, it is an old friend of viral researchers as an invader of the E. coli bacterium, which itself can threaten human health. Viruses that attack bacteria, called bacteriophages, are readily studied because a virus that attacks a unicellular host can often be observed and manipulated more easily.

“Mesyanzhinov, Arisaka and I discussed the possibility of examining T4 in closer detail,” said Rossmann. “It’s a very complicated structure consisting of more than 150 protein molecules, and we wanted to know how they were put together. So we decided to take a close look.”

It had been common scientific knowledge that the baseplate was a complicated but beautiful mechanism, one which changed its conformation from a hexagon to a star shape as it formed the irrevocable bond between virus and bacterium. Analysis of its protein building blocks required the use of both electron microscopy, needed to resolve the shapes and relationships between the proteins, and X-ray crystallography, needed for high-resolution images of the atoms within them. Each of the three researchers contributed some of the technology necessary for the analysis, which eventually revealed the structure of the baseplate.

“There are several steps a virus takes to infect a host cell,” Rossmann said. “Scientists have long known what the steps were, but no one had ever examined them on a molecular level before. This research should allow us to analyze the initial events in a viral attack. Such knowledge could be useful for targeting bacterial viruses to kill invading bacteria as an alternative to antibiotic compounds.”

While viruses are not generally thought of as prospective friends to mankind, many attack the very bacteria that cause common human illnesses, giving them potential as antibiotics.

“T4 attacks E. coli, which is well known as a threat to human health,” Rossmann said. “Many other bacteriophages also have structures similar to T4. If we could modify the proteins in the baseplate’s attachment fibers, it might enable T4 to destroy harmful bacteria. This research could be a step in that direction.”

Nanotechnology applications also are possible.

“The baseplate of this virus is essentially a complex molecular machine,” Rossmann said. “We have now obtained a clear picture of its structure, which has allowed us to suggest how it works. Building nanomachines will likely be easier if we can borrow some mechanisms already proven by nature.”

Such applications are admittedly pie in the sky for the moment, and Rossmann said the most valuable result of the research is the fundamental knowledge it reveals about viruses.

“We now have a close-up image of the machinery that guides the steps taken when a virus infects a cell,” he said. “We hope further analyses will show even greater detail.”

This research was funded in part by grants from the National Science Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Human Frontiers Science Program.

Rossmann’s team is associated with Purdue’s Markey Center for Structural Biology, which consists of laboratories that use a combination of cryoelectron microscopy, crystallography and molecular biology to elucidate the processes of viral entry, replication and pathogenesis.

Writer: Chad Boutin, (765) 494-2081, cboutin@purdue.edu

Sources: Michael G. Rossmann, (765) 494-4911, mgr@indiana.bio.purdue.edu

Petr G. Leiman, (765) 494-4925, leiman@purdue.edu

Purdue News Service: (765) 494-2096; purduenews@purdue.edu

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Humans vs Machines—Who’s Better at Recognizing Speech?

Are humans or machines better at recognizing speech? A new study shows that in noisy conditions, current automatic speech recognition (ASR) systems achieve remarkable accuracy and sometimes even surpass human…

Not Lost in Translation: AI Increases Sign Language Recognition Accuracy

Additional data can help differentiate subtle gestures, hand positions, facial expressions The Complexity of Sign Languages Sign languages have been developed by nations around the world to fit the local…

Breaking the Ice: Glacier Melting Alters Arctic Fjord Ecosystems

The regions of the Arctic are particularly vulnerable to climate change. However, there is a lack of comprehensive scientific information about the environmental changes there. Researchers from the Helmholtz Center…