Chicken embryo research tunes into inner ear

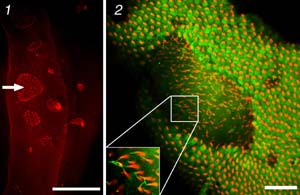

Figure 1 shows part of the cochlea in an embryonic chicken’s inner ear, where patches of vestibular hairs, used to detect balance, grew in place of those that detect sound waves. The arrow indicates one such patch. Figure 2 is a close-up that shows both types of inner-ear hairs, which grow in tufts in different locations. The inset shows the type that detects bodily motion, with the hairs themselves stained red and the telltale cilia that extend from motion-detecting tufts stained green.

Purdue University biologists have learned how to control the development of stem cells in the inner ears of embryonic chickens, a discovery which could potentially improve the ability to treat human diseases that cause deafness and vertigo.

By introducing new genes into the cell nuclei, researchers instructed the embryonic cells to develop into different adult cells than they would have ordinarily. Instead of forming the tiny hairs that the inner ear uses to detect sound waves, the stem cells matured into tissue with different kind of hairs – the sort used to keep balance. This ability to guide the choice of cell types could expand researchers’ knowledge of the inner ear and its disorders.

“We’ve essentially switched the fate of these cells,” said Donna Fekete (pronounced FEH-ka-tee), associate professor of biology in Purdue’s School of Science. “We now know at least one gene that determines what these embryonic ear cells will eventually become. As a result, we can control the outcome ourselves using gene transduction. Because so many people suffer from deafness later in life, we hope this research will yield treatments for them down the line.”

The research appears in the current (9/1) issue of Developmental Biology.

Fekete’s group stumbled onto these results after setting out to determine the function of a family of genes found in many embryonic cells. These genes, called “Wnt” genes, influence the development of organs from the brain to muscles, but they also seemed connected in some unknown capacity to the ear. Some evidence that pointed in this direction came from Fekete’s collaborators in England, who work in the lab of Julian Lewis.

“We knew the Wnt genes were present in the ears of embryonic chicks,” Fekete said. “We thought that altering the genes would perturb ear development in some way, and from a pure research perspective we wanted to know what that perturbation was. So, just to see what would happen, we used a modified retrovirus to deliver a souped-up version of a gene to make more cells experience the Wnt signal.”

Retroviruses are the Trojan horses of the gene therapy world – the infectious genetic material within their shells can be replaced with genes of the researcher’s choosing, which the retrovirus then delivers to the nucleus of the target cell. The technique, when used on the chick cells, caused them to develop into otherwise healthy tissue that ordinarily appeared in different places in the inner ear.

“The inner ear uses two kinds of tiny hairs to sense sound and bodily motion,” Fekete said. “These hairs are microscopic, and they are very different than the hairs you have on your head. The two kinds of inner ear hairs are different in one obvious respect – both types grow in tufts, but those tufts used for balance also have single, long cilia that stretch out from among the hairs. After we turned the Wnt genes on, we saw these cilia growing in places usually reserved for the non-ciliated auditory hairs.”

Many researchers overseas are trying to make stem cells develop into different types of adult cells in order to cure diseases, and Fekete said she believes this is the kind of information they will eventually need to help humans.

“More than half of the U.S. population over the age of 60 has some sort of hearing loss,” she said. “These cases are often caused by degeneration of inner ear cells damaged over the long term. Many young people also lose their hearing from sudden acoustic trauma. If we are to replace the damaged cells, we will presumably need to know how to grow the right cell type.”

Another problem this research could address is the set of disorders that cause vertigo, which includes Meniere’s disease. This disorder, which strikes approximately one person out of 2,000 annually, causes bouts of severe disequilibrium and tinnitus and lasts for life.

“An added benefit of this discovery is that it not only switches the type of surface cells responsible for hairs, it switches the type of supporting cells as well. In other words, we can make entire sections of the inner ear grow one way or the other, which might permit doctors more options.”

It will, however, be many years before such therapies might be ready for human testing.

“There’s still a great deal of work to be done here,” Fekete said. “We still are not sure what happens when you completely deactivate the Wnt signal, for example, and that’s where our research is headed next. In any case, a cure for deafness based on this discovery won’t be appearing in your drugstore anytime soon.”

Fekete did say, however, that the research was yet another example of the potential of stem cell research.

“Even if we cannot do research on human stem cells, those taken from animals can still contribute to our understanding of how living things develop,” she said. “It’s work that needs to continue.”

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health.

Writer: Chad Boutin, (765) 494-2081, cboutin@purdue.edu

Source: Donna Fekete, (765) 496-3058, dfekete@purdue.edu

Purdue News Service: (765) 494-2096; purduenews@purdue.edu

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Time to Leave Home? Revealed Insights into Brood Care of Cichlids

Shell-dwelling cichlids take intense care of their offspring, which they raise in abandoned snail shells. A team at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Intelligence used 3D-printed snail shells to…

Smart Fabrics: Innovative Comfortable Wearable Tech

Researchers have demonstrated new wearable technologies that both generate electricity from human movement and improve the comfort of the technology for the people wearing them. The work stems from an…

Going Steady—Study Reveals North Atlantic’s Gulf Stream Remains Robust

A study by the University of Bern and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the USA concludes that the ocean circulation in the North Atlantic, which includes the Gulf Stream,…