Master Gene Controls Healing Of "Skin" In Fruit Flies And Mammals

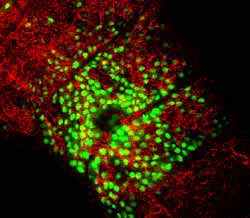

Image shows activation of cuticle repair genes (green) surrounding wound (center) in a fruit fly larva (red) <br>Credit: Kimberly Mace, UCSF

University of California, San Diego biologists and their colleagues have discovered that the genetic system controlling the development and repair of insect cuticle—the outer layer of the body surface in insects—also controls these processes in mammalian skin, a finding that could lead to new insights into the healing of wounds and treatment of cancer.

The UCSD biologists’ study, published April 15 in the journal Science identifies a master gene called grainyhead that activates wound repair genes in the cells surrounding an injury in the cuticle of a fly embryo. These wound repair genes then regenerate the injured patch of cuticle.

In a separate study published in the same issue of Science, a team of researchers led by Stephen Jane at the Royal Melbourne Hospital in Melbourne, Australia report that, although insect cuticle and the outer layer of mammal skin are very different chemically, the grainyhead gene is also essential for normal skin development and wound repair in mice.

“The discovery that grainyhead-like factors are required for the response to injury opens up new avenues of research in the field of wound healing,” said Kimberly Mace, the first author of the UCSD paper. “It also opens new avenues for cancer research, since many cancer cells activate genes normally involved in wound healing in order to kick start processes such as cell division and cell migration.”

Mace, a former graduate student of biology professor William McGinnis, who led the UCSD team, became interested in the healing of insect cuticle when she noticed lesions in the cuticle of certain fruit fly mutants. She suspected that the lesions were scar tissue resulting from the failure of the body surface barrier to develop properly. Confirming her suspicions, the mutant embryos turned out to be much more permeable to a dye than normal embryos.

The group also showed that the genes active in the mutant flies’ lesions were activated in normal flies in cells surrounding a wound created with a sterile needle. The researchers then worked backward, using bioinformatics—computational analysis of DNA sequences—to identify grainyhead as the master gene that initiates the genetic chain reaction that results in cuticle repair. Wounds in mutant flies that lack the grainyhead gene fail to heal.

“The genes involved in cuticle repair are activated very quickly, within 30 minutes after injury,” said Joseph Pearson, a graduate student working under McGinnis and a coauthor of the paper. “They are activated over many cell diameters, most strongly at the boundaries of the wound, suggesting that the grainyhead gene initiates the cuticle repair response after it receives an as-of-yet unidentified signal produced in cells adjacent to the injury.”

In its study, Jane’s team found that, like their fruit fly counterparts, mice lacking grainyhead have a much more permeable skin than normal mice and have deficient wound repair. Both groups point out in their papers that it is interesting that the regulatory mechanisms for development and repair of the surface barrier in insects and mammals have been conserved, given the differences in the molecular composition of insect cuticle and mammal skin.

“The proteins that link together to form the insect cuticle and stratum corneum—the outer layer of mammal skin—are completely different,” says McGinnis. “So it is remarkable that flies and mammals share an ancient conserved pathway to construct and repair the body envelope that protects them from sharp edges and microbes, even though that body envelope is constructed of mostly different molecules.”

In their paper, the UCSD researchers state that studying the wound response pathway in fruit flies, which are easy to manipulate genetically, may provide new insight into wound healing in mammals. For example, Mace points out that very little is known how wound tissue stops its growth behavior when the wound is healed. In addition, cancer cells evade this “stop” program, but how they do it is not well understood.

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.ucsd.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Magnetic tornado is stirring up the haze at Jupiter’s poles

Unusual magnetically driven vortices may be generating Earth-size concentrations of hydrocarbon haze. While Jupiter’s Great Red Spot has been a constant feature of the planet for centuries, University of California,…

Cause of common cancer immunotherapy side effect s

New insights into how checkpoint inhibitors affect the immune system could improve cancer treatment. A multinational collaboration co-led by the Garvan Institute of Medical Research has uncovered a potential explanation…

New tool makes quick health, environmental monitoring possible

University of Wisconsin–Madison biochemists have developed a new, efficient method that may give first responders, environmental monitoring groups, or even you, the ability to quickly detect harmful and health-relevant substances…