Bath toys show strength in numbers

Floating crescents could self-assemble into circuits

Miniature floating craft can be programmed to move and assemble in complex ways.

Harvard chemists are playing with bath toys. Floating bubble-powered craft designed to attract and repel one another, are helping them model the machinations of groups such as foraging ants, nest-building termites or schools of fish1.

Group dynamics are not always obvious from individuals’ behaviour, but emerge from their interactions. Computer models can simulate such processes. However George Whitesides and his coworkers in Cambridge, Massachusetts hope that using real experimental systems to elicit emergent properties will have a crucial advantage.

They want to exploit the self-organization inherent in their toys’ collective motions. For instance to assemble machines or electronic circuits from components that automatically swim into position.

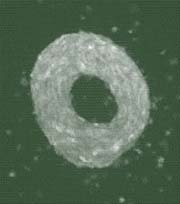

Whitesides’ team made thin half-moons of water-repelling plastic about the size of a little fingernail. When two discs get near enough on a watery surface their edges attract each other and stick loosely together. Chemically treating some of the plate edges so that they aren’t water-repellent suppresses the attraction. The team tailored the discs to attract and adhere along some edges but not others.

To make these plates self-propel, the researchers fixed a small piece of platinum-covered glass underneath one corner. When they set the discs adrift on the surface of hydrogen peroxide solution, the platinum acted as a catalyst, breaking down the hydrogen peroxide into oxygen gas. The bubbles released propelled the plates over the water surface at speeds of up to 2 cm per second for several hours.

The plates thus derive energy for their motion from their environment instead of carrying a fuel tank. Varying the catalysts or the peroxide concentration varies their speed. The asymmetric position of the platinum engine under each semicircular plate drives them into circulating movements. Which way they twirl depends on which side the engine sits.

If two plates that rotate in the same direction stick together, the assembly also rotates in that direction. If two oppositely rotating plates unite, their tendencies cancel out, and the pair moves more or less in a straight line.

So even in this very simple system a new property – straight-line motion – appears when the rotating individuals get together. “We believe”, say the researchers, “that assemblies of tens or hundreds of components may show substantially more complex behaviours”.

References

- Ismagilov, R. F., Schwartz, A., Bowden, N. & Whitesides, G. M. Autonomous movement and self-assembly. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 41, 652 – 654, (2002).

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Innovative 3D printed scaffolds offer new hope for bone healing

Researchers at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia have developed novel 3D printed PLA-CaP scaffolds that promote blood vessel formation, ensuring better healing and regeneration of bone tissue. Bone is…

The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease

ASU- and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute-led study implicates link between a common virus and the disease, which travels from the gut to the brain and may be a target for antiviral…

Molecular gardening: New enzymes discovered for protein modification pruning

How deubiquitinases USP53 and USP54 cleave long polyubiquitin chains and how the former is linked to liver disease in children. Deubiquitinases (DUBs) are enzymes used by cells to trim protein…