New channel built

Hinge benefits: ions pour through this synthetic chloride channel

Chemists copy from cells to make a tunnel for salt

Chemists have finally achieved what every human cell can do. They have designed and built from scratch a gate for electrically charged chlorine atoms to pass through1.

George Gokel and colleagues at Washington University in St Louis, Missouri, based their gate on biological proteins that transport chloride ions from one side of our cell membranes to the other. Like these, the synthetic channel can be opened and closed by applying a voltage. How this happens is not clear, even in natural ion channels.

In nature, voltage regulates ion flow to control how salty cells become. If there are more chloride ions on one side of a membrane than the other, the imbalance of electrical charge sets up a voltage across the membrane that can start or stop ions passing.

Cells use ion channels to produce electrical signals such as nerve impulses and the muscle movements that produce the heart beat. Many channels transport only one kind of ion, sodium, say, or chloride.

Similarly, the artificial channels transport chloride ions much more effectively than other ions, such as potassium or sulphate. Gokel’s group tested them in artificial particles called liposomes, which are hollow shells with walls like real cell membranes.

Several different types of protein-based chloride channel in the human body serve functions ranging from salt uptake to muscle contraction. Genetic mutations that make channels faulty are linked to heritable diseases such as cystic fibrosis and some muscle and kidney complaints.

Artificial chloride channels might one day serve as drugs against such diseases, but that’s a distant goal. At the moment, Gokel and his colleagues are simply trying to build simple molecules that can do the same job as real ion channels. Another motivation is that natural and synthetic ion transporters can act as antibiotics.

Channel tunnel

Cell membranes have an oily inside edge that repels water, so water-soluble substances such as ions need help getting across. Protein ion channels are embedded in a membrane, creating a kind of tunnel that lets ions through.

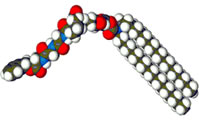

The new synthetic chloride channel tries to copy this. The molecule has a fatty, oil-soluble tail and a protein-like, ion-transporting head. The fatty tail anchors it in the membrane. The head contains a string of seven amino acids, like those that make up natural chloride channels. In particular, an amino acid known as proline is in the middle of the sequence.

Gokel’s team think that the proline is the hinge-like apex of an arch-shaped structure, and that two prolines stick together in the membrane to form a pore just wide enough for a chloride ion to pass through.

References

- Schlesinger, P. H. et al. SCMTR: a chloride-selective, membrane-anchored peptide channel that exhibits voltage gating. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 124, 1848 – 1849, (2002).

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Innovative 3D printed scaffolds offer new hope for bone healing

Researchers at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia have developed novel 3D printed PLA-CaP scaffolds that promote blood vessel formation, ensuring better healing and regeneration of bone tissue. Bone is…

The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease

ASU- and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute-led study implicates link between a common virus and the disease, which travels from the gut to the brain and may be a target for antiviral…

Molecular gardening: New enzymes discovered for protein modification pruning

How deubiquitinases USP53 and USP54 cleave long polyubiquitin chains and how the former is linked to liver disease in children. Deubiquitinases (DUBs) are enzymes used by cells to trim protein…