Tweaking a molecule's structure can send it down a different path to crystallization

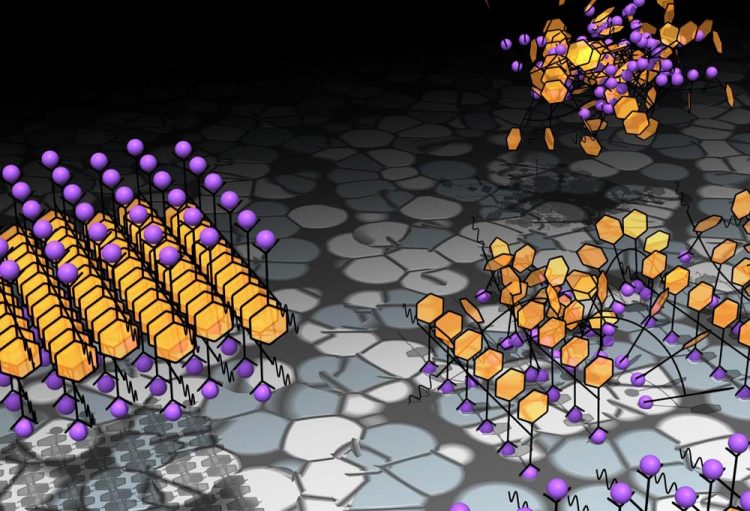

A small change to a peptoid that crystallizes in one step (left) sends the modified peptoid down a more complicated path from disordered clump to crystal (right). Credit: Jim De Yoreo/PNNL

Silky chocolate, a better medical drug, or solar panels all require the same thing: just the right crystals making up the material. Now, scientists trying to understand the paths crystals take as they form have been able to influence that path by modifying the starting ingredient.

The insights gained from the results, reported April 17 in Nature Materials, could eventually help scientists better control the design of a variety of products for energy or medical technologies.

“The findings address an ongoing debate about crystallization pathways,” said materials scientist Jim De Yoreo at the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the University of Washington. “They imply you can control the various stages of materials assembly by carefully choosing the structure of your starting molecules.”

From floppy to stiff

One of the simplest crystals, diamonds are composed of one atom — carbon. But in the living world, crystals, like the ones formed by cocoa butter in chocolate or ill-formed ones that cause sickle cell anemia, are made from molecules that are long and floppy and contain a lengthy well-defined sequence of many atoms. They can crystallize in a variety of ways, but only one way is the best. In pharmaceuticals, the difference can mean a drug that works versus one that doesn't.

Chemists don't yet have enough control over crystallization to ensure the best form, partly because chemists aren't sure how the earliest steps in crystallization happen. A particular debate has focused on whether complex molecules can assemble directly, with one molecule attaching to another, like adding one playing card at a time to a deck. They call this a one-step process, the mathematical rules for which scientists have long understood.

The other side of the debate argues that crystals require two steps to form. Experiments suggest that the beginning molecules first form a disordered clump and then, from within that group, start rearranging into a crystal, as if the cards have to be mixed into a pile first before they could form a deck. De Yoreo and his colleagues wanted to determine if crystallization always required the disordered step, and if not, why not.

Clump, snap and …

To do so, the scientists formed crystals from a somewhat simplified version of the sequence-defined molecules found in nature, a version they call a peptoid. The peptoid was not complicated — just a string of two repeating chemical subunits (think “ABABAB”) — yet complex because it was a dozen subunits long. Based on its symmetrical chemical nature, the team expected multiple molecules to come together into a larger structure, as if they were Lego blocks snapping together.

In a second series of experiments, they wanted to test how a slightly more complicated molecule assembled. So, the team added a molecule onto the initial ABABAB… sequence that stuck out like a tail. The tails attracted each other, and the team expected their association would cause the new molecules to clump. But they weren't sure what would happen afterwards.

The researchers put the peptoid molecules into solutions to let them crystallize. Then the team used a variety of analytical techniques to see what shapes the peptoids made and how fast. It turns out the two peptoids formed crystals in very different fashions.

A tail of two steps

As the scientists mostly expected, the simpler peptoid formed initial crystals a few nanometers in size that grew longer and taller as more of the peptoid molecules snapped into place. The simple peptoid followed all the rules of a one-step crystallization process.

But thrusting the tail into the mix disrupted the calm, causing a complex set of events to take place before the crystals appeared. Overall, the team showed that this more complicated peptoid first clumped together into small clusters unseen with the simpler molecules.

Some of these clusters settled onto the available surface, where they sat unchanging before suddenly converting into crystals and eventually growing into the same crystals seen with the simple peptoid. This behavior was something new and required a different mathematical model to describe it, according to the researchers. Understanding the new rules will allow researchers to determine the best way to crystallize molecules.

“We were not expecting that such a minor change makes the peptoids behave this way,” said De Yoreo. “The results are making us think about the system in a new way, which we believe will lead to more predictive control over the design and assembly of biomimetic materials.”

###

This work was supported by the Department of Energy Office of Science and PNNL's Laboratory Directed Research and Development program.

Reference: Xiang Ma, Shuai Zhang, Fang Jiao, Christina Newcomb, Yuliang Zhang, Arushi Prakash, Zhihao Liao, Marcel Baer, Christopher Mundy, Jim Pfaendtner, Aleksandr Noy, Chun-Long Chen and Jim De Yoreo, Tuning crystallization pathways through sequence-engineering of biomimetic polymers. Nature Materials April 17, 2017 DOI: 10.1038/nmat4891 (In press.)

Interdisciplinary teams at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory address many of America's most pressing issues in energy, the environment and national security through advances in basic and applied science. Founded in 1965, PNNL employs 4,400 staff and has an annual budget of nearly $1 billion. It is managed by Battelle for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. As the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, the Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information on PNNL, visit the PNNL News Center, or follow PNNL on Facebook, Google+, LinkedIn and Twitter.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

First-of-its-kind study uses remote sensing to monitor plastic debris in rivers and lakes

Remote sensing creates a cost-effective solution to monitoring plastic pollution. A first-of-its-kind study from researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities shows how remote sensing can help monitor and…

Laser-based artificial neuron mimics nerve cell functions at lightning speed

With a processing speed a billion times faster than nature, chip-based laser neuron could help advance AI tasks such as pattern recognition and sequence prediction. Researchers have developed a laser-based…

Optimising the processing of plastic waste

Just one look in the yellow bin reveals a colourful jumble of different types of plastic. However, the purer and more uniform plastic waste is, the easier it is to…