A four-stroke engine for atoms

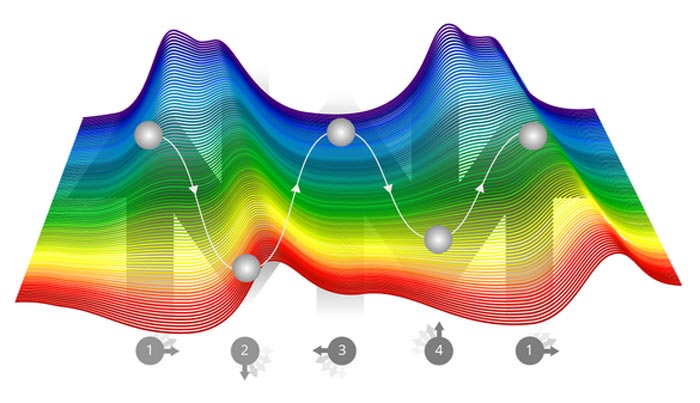

The motion of the system in an energy landscape. The system moves back and forth, much like a rolling ball on a complicated surface.

Credit: TU Wien

Switching something on and off again usually takes it back into its original state. A new magnetic material, however, has to be switched four times, while the spin of atoms moves once in a circle.

If you switch a bit in the memory of a computer and then switch it back again, you have restored the original state. There are only two states that can be called “0 and 1”.

However, an amazing effect has now been discovered at TU Wien (Vienna): In a crystal based on oxides of gadolinium and manganese, an atomic switch was found that has to be switched back and forth not just once, but twice, until the original state is reached again. During this double switching-on and switching-off process, the spin of gadolinium atoms performs one full rotation. This is reminiscent of a crankshaft, in which an up-and-down movement is converted into a circular movement.

This new phenomenon opens up interesting possibilities in material physics, even information could be stored with such systems. The strange atomic switch has now been presented in the scientific journal Nature.

Coupling of electrical and magnetic properties

Normally, a distinction is made between the electrical and magnetic properties of materials. Electrical properties are based on the fact that charge carriers move – for example electrons that travel through a metal or ions whose position is shifted.

Magnetic properties, on the other hand, are closely related to the spin of atoms – the particle’s intrinsic angular momentum, which can point in a very specific direction, much like the Earth’s axis of rotation points in a very specific direction.

However, there are also materials in which electrical and magnetic phenomena are very closely coupled. Prof. Andrei Pimenov and his team at the Institute of Solid State Physics at TU Wien are researching such materials. “We exposed a special material made of gadolinium, manganese and oxygen to a magnetic field and measured how its electrical polarisation changed in the process,” says Andrei Pimenov. “We wanted to analyse how the electrical properties of the material can be changed by magnetism. And surprisingly, we came across a completely unforeseen behaviour.”

Back to the beginning in four steps

At the beginning, the material is electrically polarised – on one side it is positively charged, on the other side negatively charged. Then you switch on a strong magnetic field – and the polarisation changes very little. However, if you then switch the magnetic field off again, a dramatic change becomes apparent: suddenly the polarisation reverses: The side that was positively charged before is now negatively charged, and vice versa.

Now you can go through the same process a second time: Again, you switch on the magnetic field and the electric polarisation remains approximately constant. If you switch off the magnetic field, the polarisation reverses again and thus returns to its original state.

“This is extremely remarkable,” says Andrei Pimenov. “We perform four different steps, each time the material changes its internal properties, but only twice does the polarisation change, so you reach the initial state only after the fourth step.”

Four-stroke engine for gadolinium

A closer look shows that the gadolinium atoms are responsible for this behaviour: They change their spin direction at each of the four steps, each time by 90 degrees. “In a sense, it’s a four-stroke engine for atoms,” says Andrei Pimenov. “In a four-stroke engine, too, it takes four steps to get back to the initial state – and the cylinder moves up and down twice in the process. In our case, the magnetic field moves up and down twice before the initial state is restored and the spin of the gadolinium atoms points in the original direction again.”

Theoretically, such materials could be used to store information: a system with four possible states would have a storage capacity of two bits per switch, instead of the usual one bit of information for “0” or “1”. But the effect is also particularly interesting for sensor technology: for example, one could produce a counter for magnetic pulses in this way. The effect provides important new inputs for theoretical research: it is another example of a so-called “topological effect”, a class of material effects that have been attracting a lot of attention in solid-state physics for years and should enable the development of new materials.

Journal: Nature

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-04851-6.

Method of Research: Experimental study

Subject of Research: Not applicable

Article Title: ‘Topologically protected magnetoelectric switching in a multiferroic

Article Publication Date: 6-Jul-2022

Media Contacts

Florian Aigner

Vienna University of Technology

pr@tuwien.ac.at

Office: 0043-158-801 x41027

Andrei Pimenov

TU Wien

andrei.pimenov@tuwien.ac.at

Office: +43-1-58801-13723

All latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

Innovative 3D printed scaffolds offer new hope for bone healing

Researchers at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia have developed novel 3D printed PLA-CaP scaffolds that promote blood vessel formation, ensuring better healing and regeneration of bone tissue. Bone is…

The surprising role of gut infection in Alzheimer’s disease

ASU- and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute-led study implicates link between a common virus and the disease, which travels from the gut to the brain and may be a target for antiviral…

Molecular gardening: New enzymes discovered for protein modification pruning

How deubiquitinases USP53 and USP54 cleave long polyubiquitin chains and how the former is linked to liver disease in children. Deubiquitinases (DUBs) are enzymes used by cells to trim protein…