Ancient Signals From the Early Universe

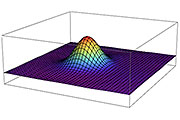

According to the calculations of Prof. Stefan Antusch and his team, oscillons produced a characteristic peak in the otherwise broad spectrum of gravitational waves. University of Basel, Department of Physics

Although Albert Einstein had already predicted the existence of gravitational waves, their existence was not actually proven until fall 2015, when highly sensitive detectors received the waves formed during the merging of two black holes. Gravitational waves are different from all other known waves.

As they travel through the universe, they shrink and stretch the space-time continuum; in other words, they distort the geometry of space itself. Although all accelerating masses emit gravitational waves, these can only be measured when the mass is extremely large, as is the case with black holes or supernovas.

Gravitational waves transport information from the Big Bang

However, gravitational waves not only provide information on major astrophysical events of this kind but also offer an insight into the formation of the universe itself. In order to learn more about this stage of the universe, Prof. Stefan Antusch and his team from the Department of Physics at the University of Basel are conducting research into what is known as the stochastic background of gravitational waves.

This background consists of gravitational waves from a large number of sources that overlap with one another, together yielding a broad spectrum of frequencies. The Basel-based physicists calculate predicted frequency ranges and intensities for the waves, which can then be tested in experiments.

A highly compressed universe

Shortly after the Big Bang, the universe we see today was still very small, dense, and hot. “Picture something about the size of a football,” Antusch explains. The whole universe was compressed into this very small space, and it was extremely turbulent. Modern cosmology assumes that at that time the universe was dominated by a particle known as the inflaton and its associated field.

Oscillons generate a powerful signal

The inflaton underwent intensive fluctuations, which had special properties. They formed clumps, for example, causing them to oscillate in localized regions of space. These regions are referred to as oscillons and can be imagined as standing waves. “Although the oscillons have long since ceased to exist, the gravitational waves they emitted are omnipresent – and we can use them to look further into the past than ever before,” says Antusch.

Using numerical simulations, the theoretical physicist and his team were able to calculate the shape of the oscillon’s signal, which was emitted just fractions of a second after the Big Bang. It appears as a pronounced peak in the otherwise rather broad spectrum of gravitational waves.

“We would not have thought before our calculations that oscillons could produce such a strong signal at a specific frequency,” Antusch explains. Now, in a second step, experimental physicists must actually prove the signal’s existence using detectors.

Original article

Stefan Antusch, Francesco Cefalà, and Stefano Orani

Gravitational Waves from Oscillons after Inflation

Physical Review Letters (2017), doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.011303

Further information

Prof. Dr. Stefan Antusch, University of Basel, Department of Physics, Tel. +41 61 207 39 18, email: stefan.antusch@unibas.ch

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.unibas.chAll latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

First-of-its-kind study uses remote sensing to monitor plastic debris in rivers and lakes

Remote sensing creates a cost-effective solution to monitoring plastic pollution. A first-of-its-kind study from researchers at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities shows how remote sensing can help monitor and…

Laser-based artificial neuron mimics nerve cell functions at lightning speed

With a processing speed a billion times faster than nature, chip-based laser neuron could help advance AI tasks such as pattern recognition and sequence prediction. Researchers have developed a laser-based…

Optimising the processing of plastic waste

Just one look in the yellow bin reveals a colourful jumble of different types of plastic. However, the purer and more uniform plastic waste is, the easier it is to…