How do electrons close to Earth reach almost the speed of light?

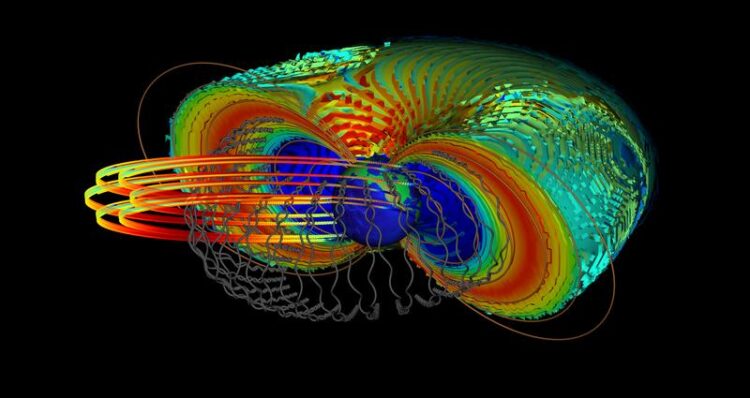

The contours in color show the intensities of the radiation belts. Grey lines show the trajectories of the relativistic electrons in the radiation belts. Concentric circular lines show the trajectory of scientific satellites traversing this dangerous region in space.

Credit: Ingo Michaelis and Yuri Shprits, GFZ

New study found that electrons can reach ultra-relativistic energies for very special conditions in the magnetosphere when space is devoid of plasma.

New study found that electrons can reach ultra-relativistic energies for very special conditions in the magnetosphere when space is devoid of plasma.

Recent measurements from NASA’s Van Allen Probes spacecraft showed that electrons can reach ultra-relativistic energies flying at almost the speed of light. Hayley Allison, Yuri Shprits and collaborators from the German Research Centre for Geosciences have revealed under which conditions such strong accelerations occur. They had already demonstrated in 2020 that during solar storm plasma waves play a crucial role for that. However, it was previously unclear why such high electron energies are not achieved in all solar storms. In the journal Science Advances, Allison, Shprits and colleagues now show that extreme depletions of the background plasma density are crucial.

Ultra-relativistic electrons in space

At ultra-relativistic energies, electrons move at almost the speed of light. Then the laws of relativity become most important. The mass of the particles increases by a factor ten, time is slowing down, and distance decreases. With such high energies, charged particles become most dangerous to even the best protected satellites. As almost no shielding can stop them, their charge can destroy sensitive electronics. Predicting their occurrence – for example, as part of the observations of space weather practised at the GFZ – is therefore very important for modern infrastructure.

To investigate the conditions for the enormous accelerations of the electrons, Allison and Shprits used data from a twin mission, the “Van Allen Probes”, which the US space agency NASA had launched in 2012. The aim was to make detailed measurements in the radiation belt, the so-called Van Allen belt, which surrounds the Earth in a donut shape in terrestrial space. Here – as in the rest of space – a mixture of positively and negatively charged particles forms a so-called plasma. Plasma waves can be understood as fluctuations of the electric and magnetic field, excited by solar storms. They are an important driving force for the acceleration of electrons.

Data analysis with machine learning

During the mission, both solar storms that produced ultra-relativistic electrons and storms without this effect were observed. The density of the background plasma turned out to be a decisive factor for the strong acceleration: electrons with the ultra-relativistic energies were only observed to increase when the plasma density dropped to very low values of only about ten particles per cubic centimetre, while normally such density is five to ten times higher.

Using a numerical model that incorporated such extreme plasma depletion, the authors showed that periods of low density create preferential conditions for the acceleration of electrons – from an initial few hundred thousand to more than seven million electron volts. To analyse the data from the Van Allen probes, the researchers used machine learning methods, the development of which was funded by the GEO.X network. They enabled the authors to infer the total plasma density from the measured fluctuations of electric and magnetic field.

The crucial role of plasma

“This study shows that electrons in the Earth’s radiation belt can be promptly accelerated locally to ultra-relativistic energies, if the conditions of the plasma environment – plasma waves and temporarily low plasma density – are right. The particles can be regarded as surfing on plasma waves. In regions of extremely low plasma density they can just take a lot of energy from plasma waves. Similar mechanisms may be at work in the magnetospheres of the outer planets such as Jupiter or Saturn and in other astrophysical objects”, says Yuri Shprits, head of the GFZ section Space physics and space weather and Professor at University of Potsdam.

“Thus, to reach such extreme energies, a two-stage acceleration process is not needed, as long assumed – first from the outer region of the magnetosphere into the belt and then inside. This also supports our research results from last year,” adds Hayley Allison, PostDoc in the Section Space physics and space weather.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

Largest magnetic anisotropy of a molecule measured at BESSY II

At the Berlin synchrotron radiation source BESSY II, the largest magnetic anisotropy of a single molecule ever measured experimentally has been determined. The larger this anisotropy is, the better a…

Breaking boundaries: Researchers isolate quantum coherence in classical light systems

LSU quantum researchers uncover hidden quantum behaviors within classical light, which could make quantum technologies robust. Understanding the boundary between classical and quantum physics has long been a central question…

MRI-first strategy for prostate cancer detection proves to be safe

Active monitoring is a sufficiently safe option when prostate MRI findings are negative. There are several strategies for the early detection of prostate cancer. The first step is often a…