Princeton and General Atomics Scientists Make Breakthrough in Understanding How to Control Intense Heat Bursts in Fusion Experiments

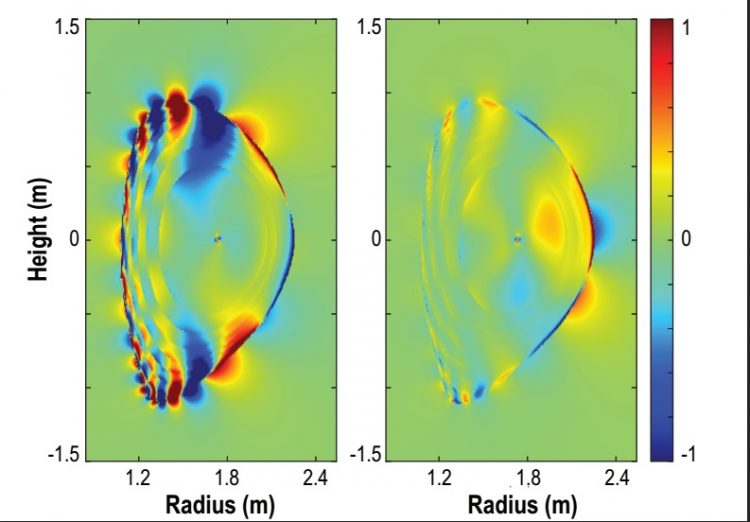

General Atomics Computer simulation of a cross-section of a DIII-D plasma responding to tiny magnetic fields. The left image models the response that suppressed the ELMs while the right image shows a response that was ineffective.

Scientists performed the experiments on the DIII-D National Fusion Facility, a tokamak operated by General Atomics in San Diego. The findings represent a key step in predicting how to control heat bursts in future fusion facilities including ITER, an international experiment under construction in France to demonstrate the feasibility of fusion energy. This work is supported by the DOE Office of Science.

The studies build upon previous work pioneered on DIII-D showing that these intense heat bursts – called “ELMs” for short – could be suppressed with tiny magnetic fields. These tiny fields cause the edge of the plasma to smoothly release heat, thereby avoiding the damaging heat bursts.

But until now, scientists did not understand how these fields worked. “Many mysteries surrounded how the plasma distorts to suppress these heat bursts,” said Carlos Paz-Soldan, a General Atomics scientist and lead author of the first of the two papers that report the seminal findings back-to-back in the same issue of Physical Review Letters this week.

Paz-Soldan and a multi-institutional team of researchers found that tiny magnetic fields applied to the device can create two distinct kinds of response, rather than just one response as previously thought.

The new response produces a ripple in the magnetic field near the plasma edge, allowing more heat to leak out at just the right rate to avert the intense heat bursts. Researchers applied the magnetic fields by running electrical current through coils around the plasma. Pickup coils then detected the plasma response, much as the microphone on a guitar picks up string vibrations.

The second result, led by PPPL scientist Raffi Nazikian, who heads the PPPL research team at DIII-D, identified the changes in the plasma that lead to the suppression of the large edge heat bursts or ELMs. The team found clear evidence that the plasma was deforming in just the way needed to allow the heat to slowly leak out.

The measured magnetic distortions of the plasma edge indicated that the magnetic field was gently tearing in a narrow layer, a key prediction for how heat bursts can be prevented. “The configuration changes suddenly when the plasma is tapped in a certain way,” Nazikian said, “and it is this response that suppresses the ELMs.”

The work involved a multi-institutional team of researchers who for years have been working toward an understanding of this process. These researchers included people from General Atomics, PPPL, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Columbia University, Australian National University, the University of California-San Diego, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and several others.

The new results suggest further possibilities for tuning the magnetic fields to make ELM-control easier. These findings point the way to overcoming a persistent barrier to sustained fusion reactions. “The identification of the physical processes that lead to ELM suppression when applying a small 3D magnetic field to the inherently 2D tokamak field provides new confidence that such a technique can be optimized in eliminating ELMs in ITER and future fusion devices,” said Mickey Wade, the DIII-D program director.

The results further highlight the value of the long-term multi-institutional collaboration between General Atomics, PPPL and other institutions in DIII-D research. This collaboration, said Wade, “was instrumental in developing the best experiment possible, realizing the significance of the results, and carrying out the analysis that led to publication of these important findings.”

PPPL, on Princeton University's Forrestal Campus in Plainsboro, N.J., is devoted to creating new knowledge about the physics of plasmas — ultra-hot, charged gases — and to developing practical solutions for the creation of fusion energy. The Laboratory is managed by the University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science, which is the largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

General Atomics has participated in fusion research for over 50 years and presently operates the DIII-D National Fusion Facility for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science with a mission “to provide the physics basis for the optimization of the tokamak approach to fusion energy production.” The General Atomics group of companies is a world renowned leader in developing high-technology systems ranging from the nuclear fuel cycle to electromagnetic systems; remotely operated surveillance aircraft; airborne sensors; advanced electronic, wireless, and laser technologies; and biofuels.

Contact Information

John Greenwald

Science Editor

jgreenwa@pppl.gov

Phone: 609-243-2672

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.pppl.govAll latest news from the category: Physics and Astronomy

This area deals with the fundamental laws and building blocks of nature and how they interact, the properties and the behavior of matter, and research into space and time and their structures.

innovations-report provides in-depth reports and articles on subjects such as astrophysics, laser technologies, nuclear, quantum, particle and solid-state physics, nanotechnologies, planetary research and findings (Mars, Venus) and developments related to the Hubble Telescope.

Newest articles

Can lab-grown neurons exhibit plasticity?

“Neurons that fire together, wire together” describes the neural plasticity seen in human brains, but neurons grown in a dish don’t seem to follow these rules. Neurons that are cultured…

Unlocking the journey of gold through magmatic fluids

By studying sulphur in magmatic fluids at extreme pressures and temperatures, a UNIGE team is revolutionising our understanding of gold transport and ore deposit formation. When one tectonic plate sinks…

3D concrete printing method that captures carbon dioxide

Scientists at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) have developed a 3D concrete printing method that captures carbon, demonstrating a new pathway to reduce the environmental impact of the construction…