Risk of infection with COVID-19 from singing: First results of aerosol study with the Bavarian Radio Chorus

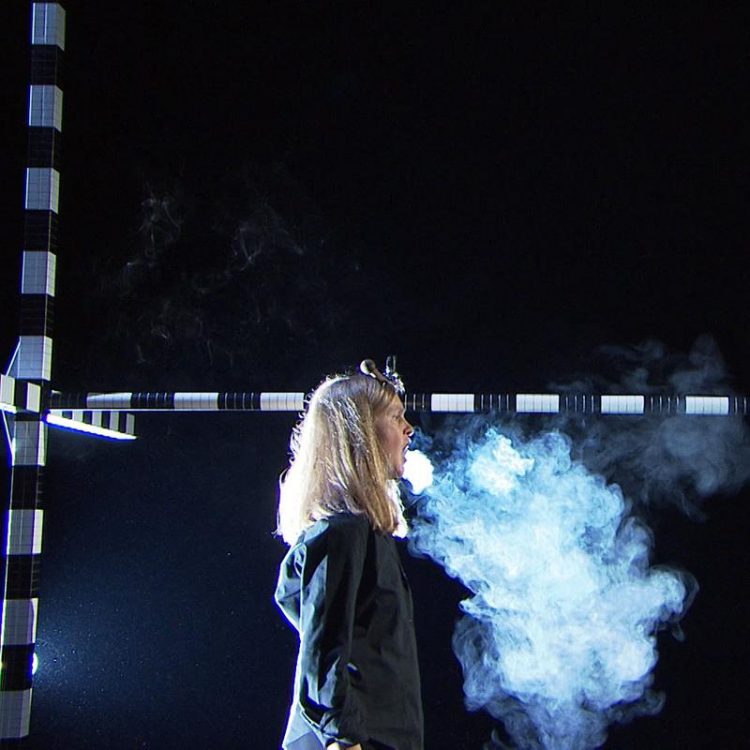

Singer from the Bavarian Broadcasting Chorus during the series of experiments in the BR studio in Unterföhring Bavarian Broadcasting (BR)

Susanne Vongries, manager of the BR Chorus, describes the initial situation: ‘After the initial shock of lockdown and once we’d reviewed the restrictive guidelines, we quickly started to think about how we could resume working as musicians and what repertoire we could perform, with the condition that protecting our choir members and their health was our top priority.’

However, since there is very little reliable scientific knowledge available worldwide, particularly regarding the risk of infection for choral ensembles, Bavarian Broadcasting sought expert advice from Prof. Matthias Echternach, head of the Division of Phoniatrics and Paediatric Audiology at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, LMU University Hospital Munich and himself a trained singer.

The study concept

Prof. Echternach, together with Dr Stefan Kniesburges, a specialist in fluid mechanics at Universitätsklinikum Erlangen (FAU), designed a study to measure the emission and distribution of both larger droplets and the smallest particles – known as aerosols – during singing with and without words and during speaking.

The particular focus here, in contrast to studies that examine the flow velocities of particles, was that these experiments investigated the transmission and distribution of droplets and aerosols within a room.

To achieve this, the scientists constructed two experimental sets in Studio 2 at Bavarian Broadcasting’s studio in Unterföhring, Munich. Between 20 and 26 May 2020, ten test subjects from the BR Chorus and nine wind players from the BR Symphony Orchestra took it in turns to sing, speak and play specific passages at different volumes on these two sets. Data from the wind instrument measurements are still being evaluated.

Measuring visible aerosol clouds

The first set used high-speed cameras and laser equipment to allow the scattering of larger droplets to be investigated. How are these droplets emitted from the mouth or the instrument, and which spoken or sung passages produced the largest quantity of droplets?

On the second set, cameras and white light were used to analyse how the even smaller aerosols leave the mouth and nose and how these spread within the room. In order to render the distribution of these tiny particles visible, the test subjects inhaled a carrier solution from e-cigarettes. This was then visible in bright light during and after vocalising.

Conclusion: more space to the front than to the side

Evaluating the measurements of the aerosol clouds emitted showed that choir members would need to maintain a greater distance from colleagues in front of them than from those at either side. However, this presupposes that the aerosol is regularly removed from the room via a constant flow of fresh air. Even better would be to have partitions between the singers.

‘For the sung text, we measured distances from the centre of about one metre forwards, but some singers also achieved widths of 1 to 1.5 metres. That means that safe distances of 1.5 metres are probably too low and distances of 2 to 2.5 metres seem more sensible’, says Prof. Echternach. ‘However, the data only refer to direct transmission at natural speed during singing. For the singers’ safety, it’s important that the aerosols are also continuously removed from the room so that there’s no accumulation,’ he adds. ‘We noted significantly smaller distances towards the side than towards the front, meaning that distances here could be lower’, says Stefan Kniesburges. ‘But a constant supply of fresh air is required here as well, so as to remove aerosols from the air.’

Singing in a mask?

According to Kniesburges, tests with face masks revealed that ‘singing with surgical masks filters out the large droplets completely and the aerosols partially, but a portion of the aerosols are emitted in a jet-like fashion slightly upwards and to the sides.’ This occurs because the masks do not seal totally at the sides and over the nose. The researchers found that singing with a mask could be an option, as it reduced particle leakage, but this is not really suitable for professional choirs: ‘You have to be able to articulate well and of course you need every little nuance of sound,’ says Echternach. He does, however, think that church or other non-professional choirs may sing with masks for the preventive effect.

Prof. Matthias Echternach

Head, Division of Phoniatrics and Paediatric Audiology

Department of Otorhinolaryngology

LMU University Hospital Munich

Tel: +49 (0)89 4400 73890

Email: matthias.echternach@med.uni-muenchen.de

Dr Stefan Kniesburges

Phoniatrics and Paediatric Audiology

Department of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery

Universitätsklinikum Erlangen

Tel: +49 (0)9131 8532616

Email: stefan.kniesburges@uk-erlangen.de

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.lmu-klinikum.deAll latest news from the category: Studies and Analyses

innovations-report maintains a wealth of in-depth studies and analyses from a variety of subject areas including business and finance, medicine and pharmacology, ecology and the environment, energy, communications and media, transportation, work, family and leisure.

Newest articles

Largest magnetic anisotropy of a molecule measured at BESSY II

At the Berlin synchrotron radiation source BESSY II, the largest magnetic anisotropy of a single molecule ever measured experimentally has been determined. The larger this anisotropy is, the better a…

Breaking boundaries: Researchers isolate quantum coherence in classical light systems

LSU quantum researchers uncover hidden quantum behaviors within classical light, which could make quantum technologies robust. Understanding the boundary between classical and quantum physics has long been a central question…

MRI-first strategy for prostate cancer detection proves to be safe

Active monitoring is a sufficiently safe option when prostate MRI findings are negative. There are several strategies for the early detection of prostate cancer. The first step is often a…